Between the historical and the fantastical: on Don Lawrence’s ‘Karl the Viking’

18th January 2022

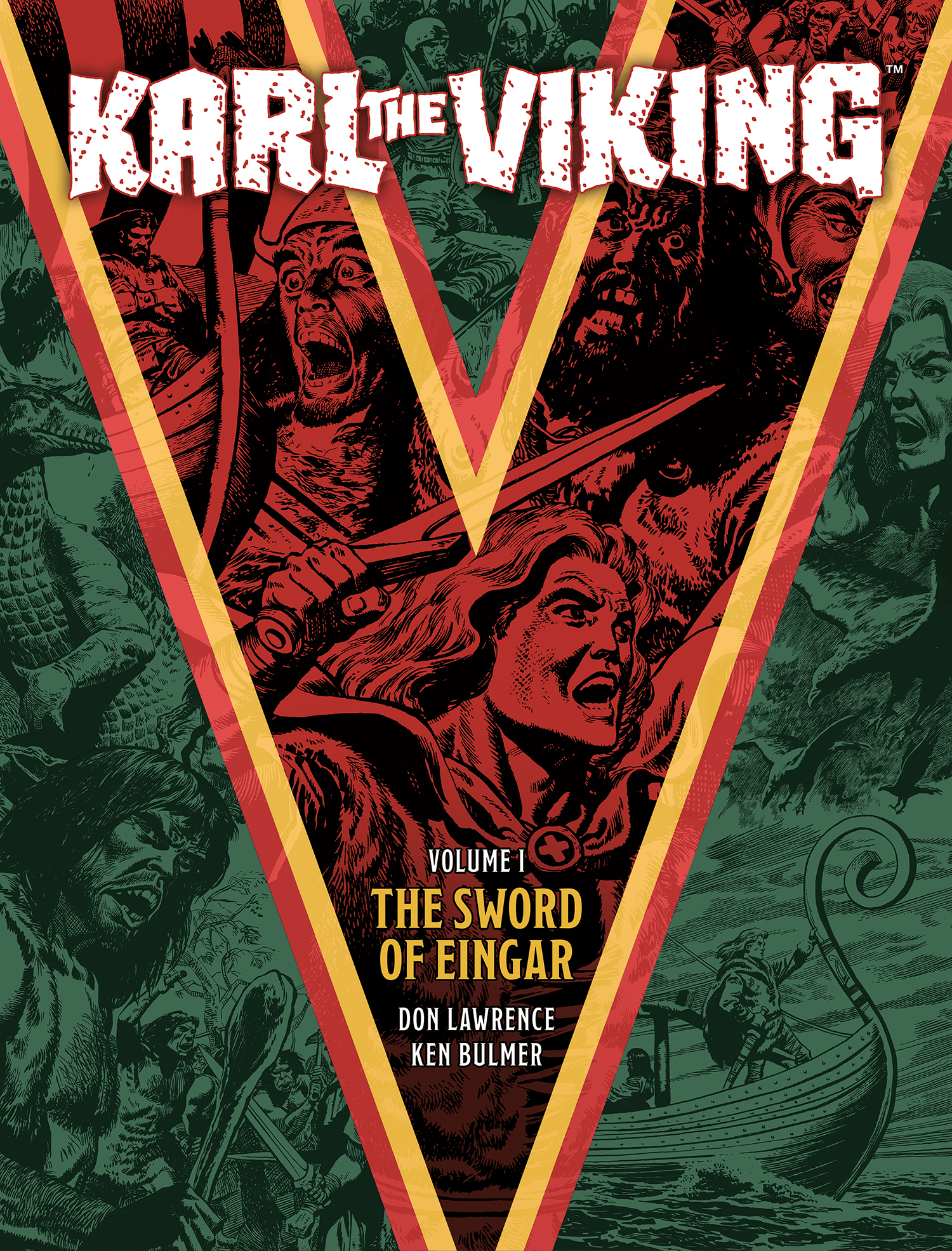

Before his incredible artwork on The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire, Don Lawrence had already proven himself to be a unique and stunning talent with his work on historical fantasy series Karl the Viking for the pages of Lion.

Continuing our series of short essays commissioned from selected comics critics that explore 2000 AD and the Treasury of British Comics’ latest graphic novel collections, Doris V. Sutherland reviews the epic sweep of this breathtakingly drawn series…

Created by artist Don Lawrence and writer Ted Cowan, Karl the Viking was one of the more durable features to appear in Lion, not only running for a chunk of the sixties but also being reprinted multiple times since then. Now, Karl’s first six adventures have been gathered together for a Treasury of British Comics collection, allowing both newcomers and the nostalgic alike to see just what made this character a hit with Lion’s readers…

The first tale, “The Sword of Eingar”, includes Karl’s origin story. The saga opens with a band of Vikings pillaging a Saxon village. One of the Saxons takes arms against the Viking leader, Eignar the manslayer; and although the Saxon is defeated, Eingar is impressed by the man’s skill (“Indeed this is no ordinary Saxon! He fights like a man–like a Viking!”). He decides to adopt the Saxon’s orphaned baby, naming the boy Karl and raising him “in the harsh, barbaric manner of the Norsemen.” Karl grows into something of an inbetweener, inheriting the martial skill of the Vikings while retaining the wisdom and nobility that the comic associates with Saxons.

After Eingar disturbs a Celtic burial ground, a mysterious crone shows up and curses the Vikings. Sure enough, bad luck follows and Eingar disappears. Karl is next in line to become chief, but his ethnic background proves a point of contention. And so, he is forced to compete with a brutal Viking named Skurl to find Eingar’s sword and prove himself worthy. Along the way, Karl meets his Saxon kindred and strikes a deal with the locals: “If I become chieftain of his markland, this village will never again suffer at Viking hands”. The story’s finale puts Karl against both his rival Skurl and the villainous nobleman who killed Eingar.

Much of Karl the Viking feels like a halfway point between the worthy history lessons of the Eagle and the unabashed, escapist pulp of its less reputable rivals. Don Lawrence’s artwork is lavish stuff indeed, produced in an era when historical comics were treated as an extension to schoolbook illustrations. The characters are rendered with care, as are the backgrounds of thatched villages, craggy cliffs, foreboding forests and roaring seas. The weapons, armour and sailing vessels are similarly detailed, although as the strip progresses, it becomes clear that Karl inhabits a carefree mash-up of different eras. The stories are often violent but, in contrast to the later likes of Action and 2000 AD, bloodshed is seldom front-and-centre, instead being left to the imagination or summarised in textual captions (“Soon the crackle of flames from plundered cottages mingled with the screams of the dying”).

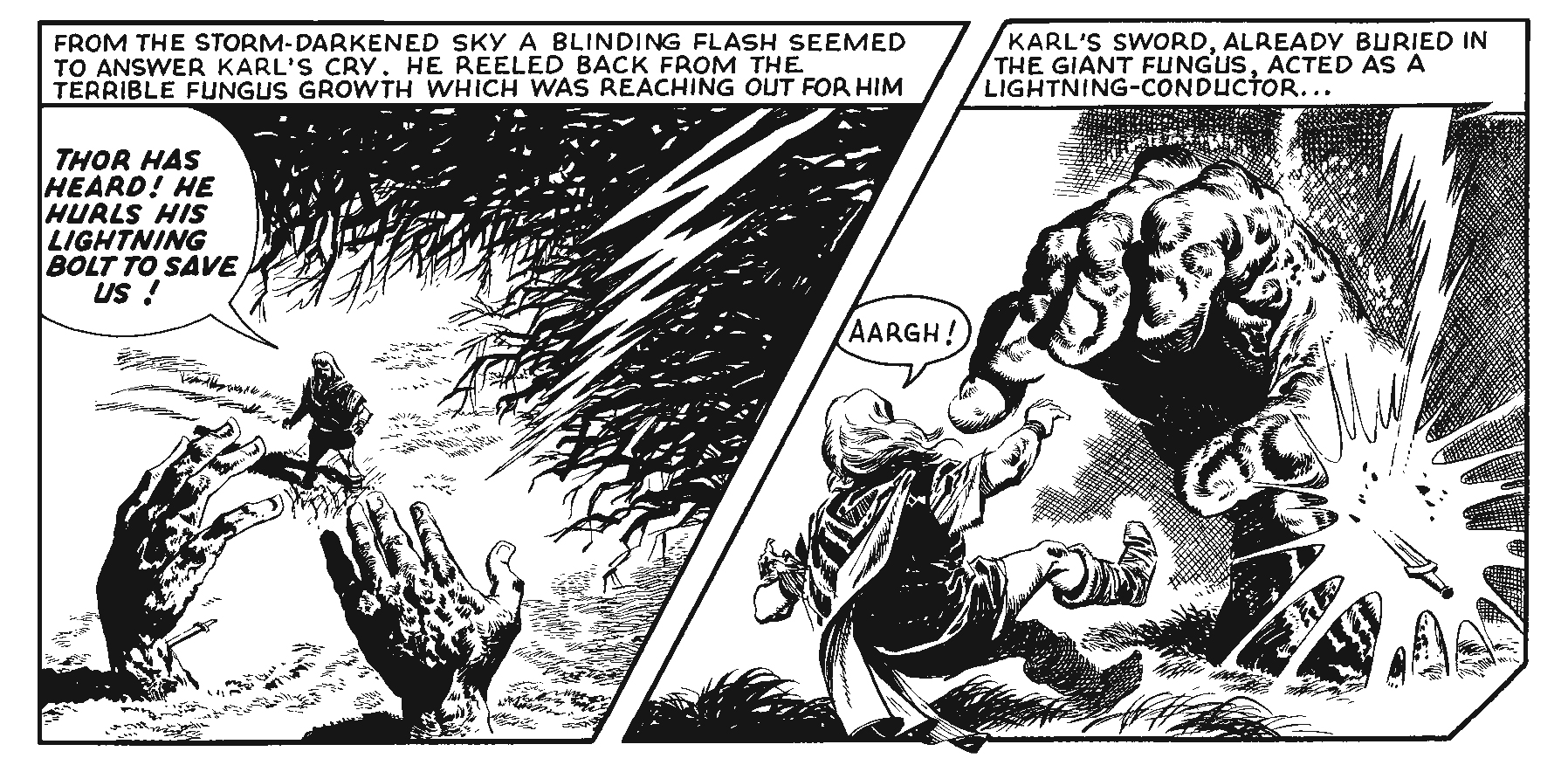

In Ted Cowan’s scripts, romance trumps historical accuracy. Karl’s adventures have a thick vein of fantasy: characters divine images in smoke or water, while thunderbolts appear at fortuitous moments as though hurled by Thor himself. “The Sword of Eingar” plays things relatively safe in this respect, but the second story plunges headlong into fanciful adventures with anachronisms that would make Asterix blush.

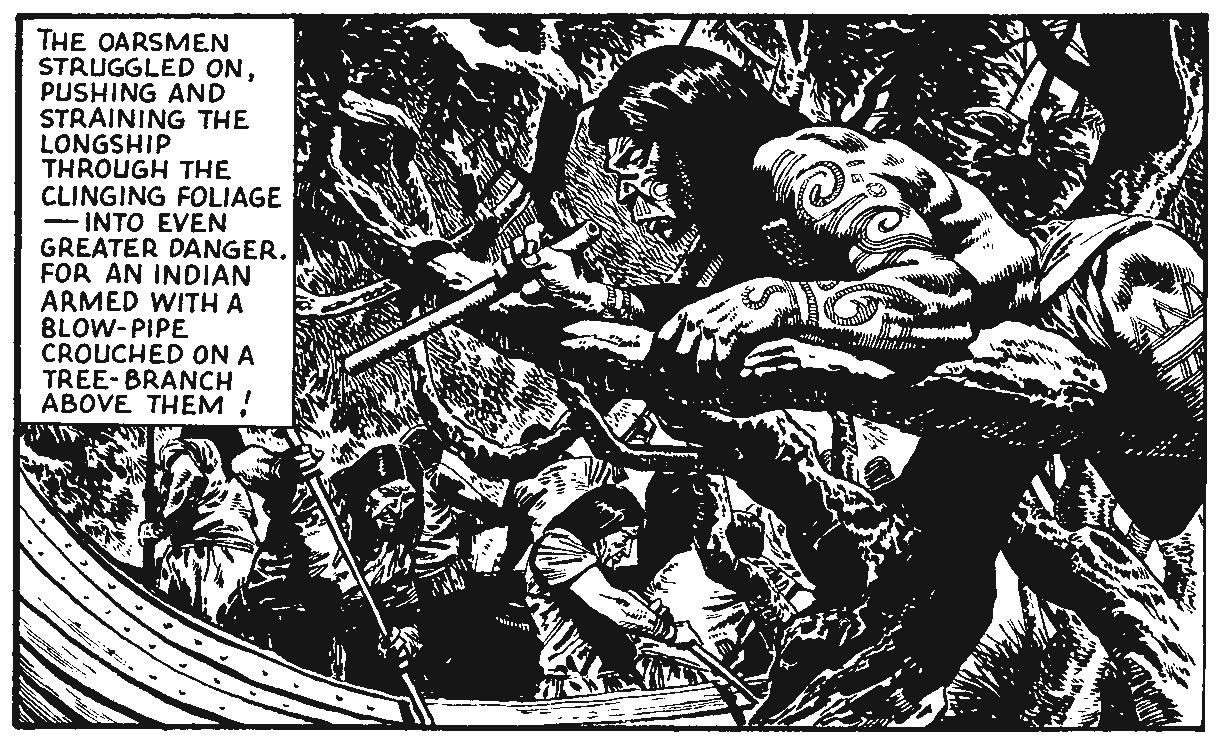

In “The Long Voyage to Oxaca” Karl meets a small group of Mesoamericans who were set adrift at sea. One of them happens to be the rightful heir to the throne, and Karl is duty-bound to get the boy-king Tihuana back home again. The journey takes Karl and company to some remarkable places: a land in which peaceful cavemen need help fending themselves against hostile neanderthals and even dinosaurs; Atlantis, shortly before its destruction; and a vast river that is familiar to the Aztecs (“We call it the Amazona, which means ‘the breaker of boats’!”) The weirdness continues to the very end of the journey. After making the brisk trip from the Amazon to Mexico, Karl must face Tihuana’s evil uncle and his soldiers – who wear what appears to be Mongolian armour. Did Genghis Khan reach the Americas before the Vikings…?

“Selgor the Wolf” puts Karl on a journey to find the fabled riches of Woden, said to be located under a gigantic yellow eye. The climax sums up how Karl’s adventures teeter between magic and rationalism. The “eye” turns out to be a giant mirror capable of reflecting sunlight and burning ships; if ancient writers are to be believed, such a device was actually invented by Archimedes. Yet the treasure’s guardian is pure fantasy: a gigantic caterpillar-like creature that catches humans on its tongue the way a frog catches flies. Serving as antagonist in this story is the berserker Selgor, a man prone to taking on a lupine aspect when hit by bloodlust (“Look! His face has changed! He’s more like an animal!”). Selgor returns in “The False God”, now masquerading as Thor – and convincing enough Vikings that Karl is deemed a blasphemer. In another anachronistic flourish, the action climaxes in Sicily – which is apparently still populated by ancient Romans.

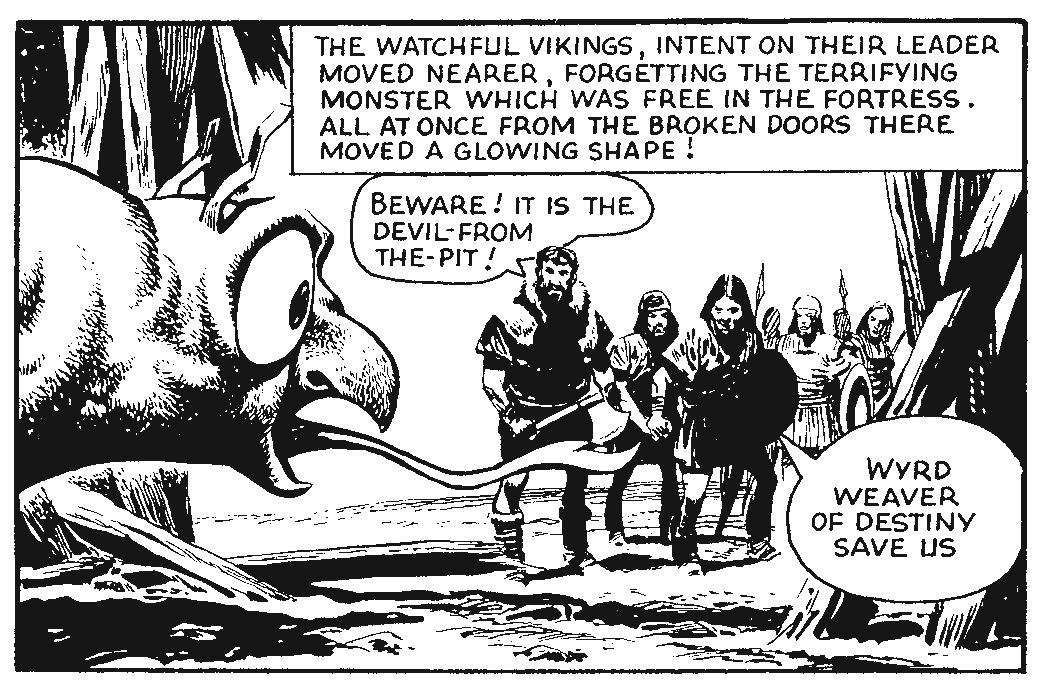

The weirdest story in the collection is “The Powers of Helvud”. This time around the enemy is not a mortal man but rather a swarm of fungal spores, depicted as small winged globes, that blow into Karl’s homeland from afar and form growths resembling clenched fists (“By Odin, they look too much like human hands!”) The Vikings try cooking the fungus, and despite Karl’s protestations (“Fools, the fungus is accursed! It has been sent by a demon-of-darkness”) one man actually eats it, promptly going violently mad and glowing. This turns out to be the work of an evil spirit named Helvud, who commands a forest full of tree-demons – and who himself turns out t resemble a gigantic specimen of hand-fungus (“Odin, god of battles, ride on your eight-hooved horse and grant us life until the evil of the fungus has been crushed!”). The final story, “El Sarid the Merciless”, is comparatively sedate, Karl’s opponent being a Saracen hypnotist.

Whether it is depicting grimy, quasi-historical combat or plunging headlong into sword-and-sorcery, Karl the Viking remains a sumptuous strip, standing out from its contemporaries just as its handsome protagonist stands out amongst his uncouth warriors.

Doris V. Sutherland is the UK-based author behind the independent comic series Midnight Widows and official tie-ins for television series including Doctor Who and The Omega Factor. She has contributed articles to Women Write About Comics, Amazing Stories, Killer Horror Critic, Belladonna Magazine and other outlets.

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.