“But don’t just take my word”: Power and Surveillance in ‘The Thirteenth Floor’

27th September 2021

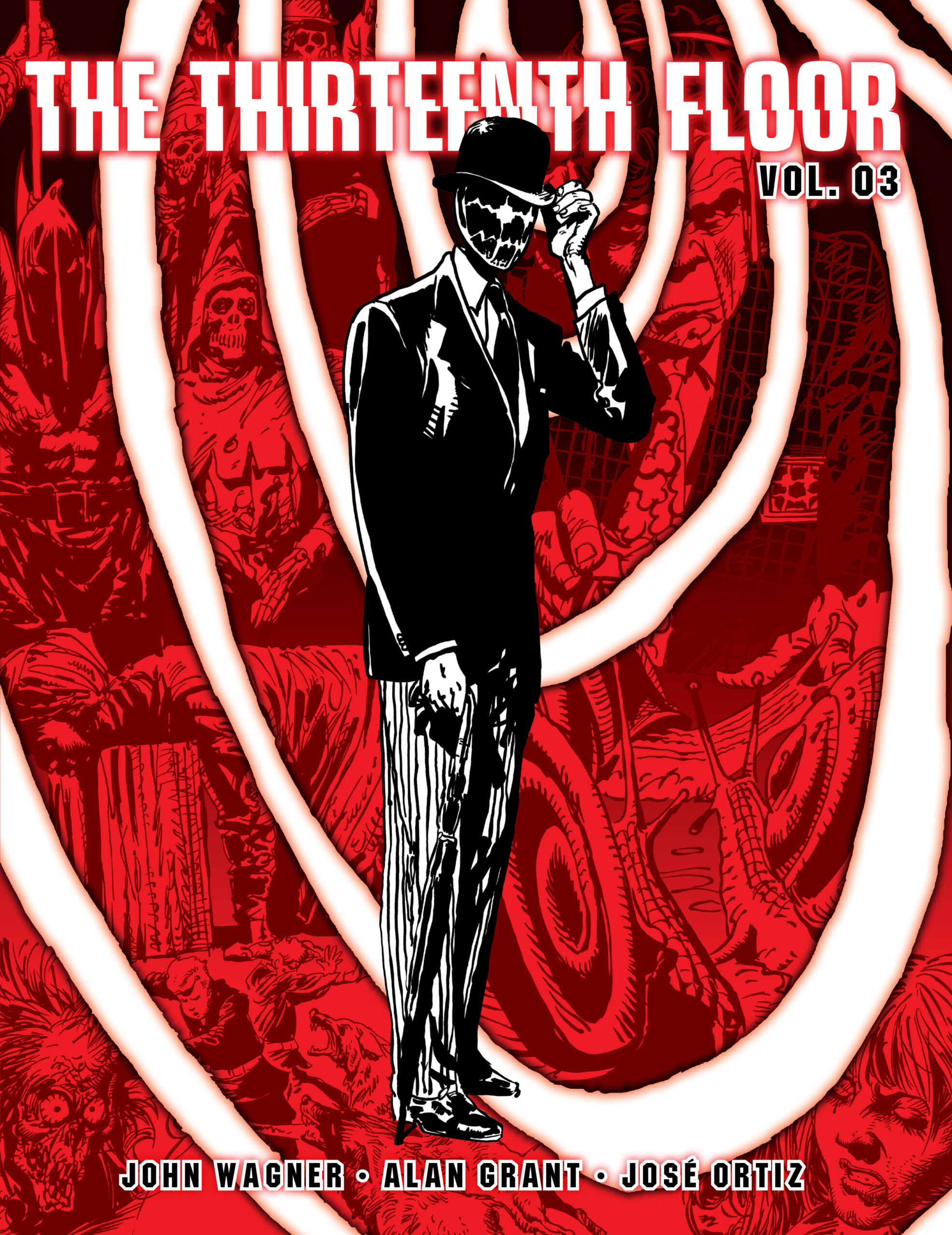

The third and final collection of The Thirteenth Floor is out now, bringing to a close the deliciously devious deviations of mad Max, the murderous AI caretaker of Maxwell Towers.

Continuing our series of short essays commissioned from selected comics critics that explore 2000 AD and the Treasury of British Comics’ latest graphic novel collections, Tiffany Babb examines ideas of power and surveillance in John Wagner, Alan Grant, and José Ortiz’s comic horror masterpiece…

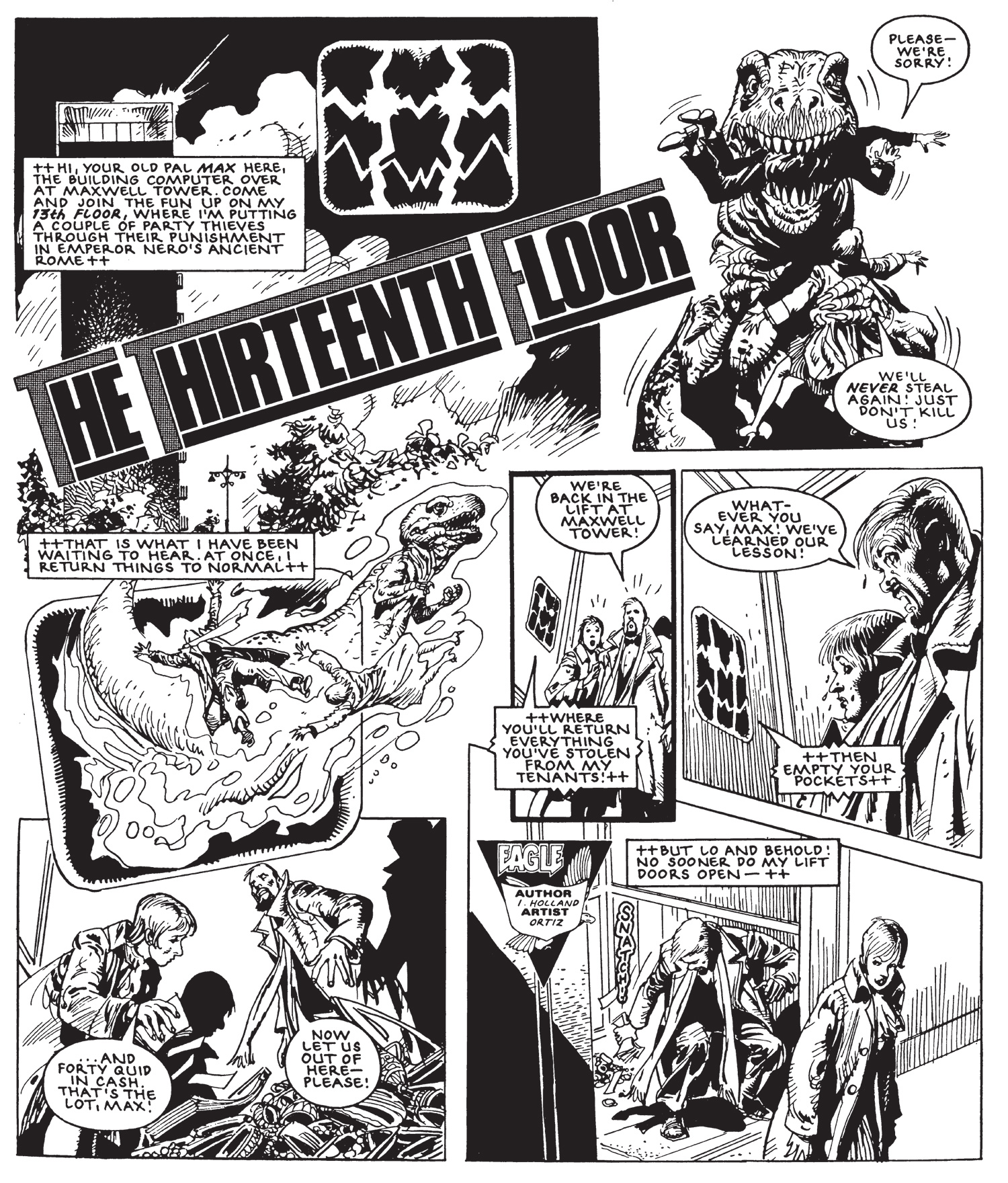

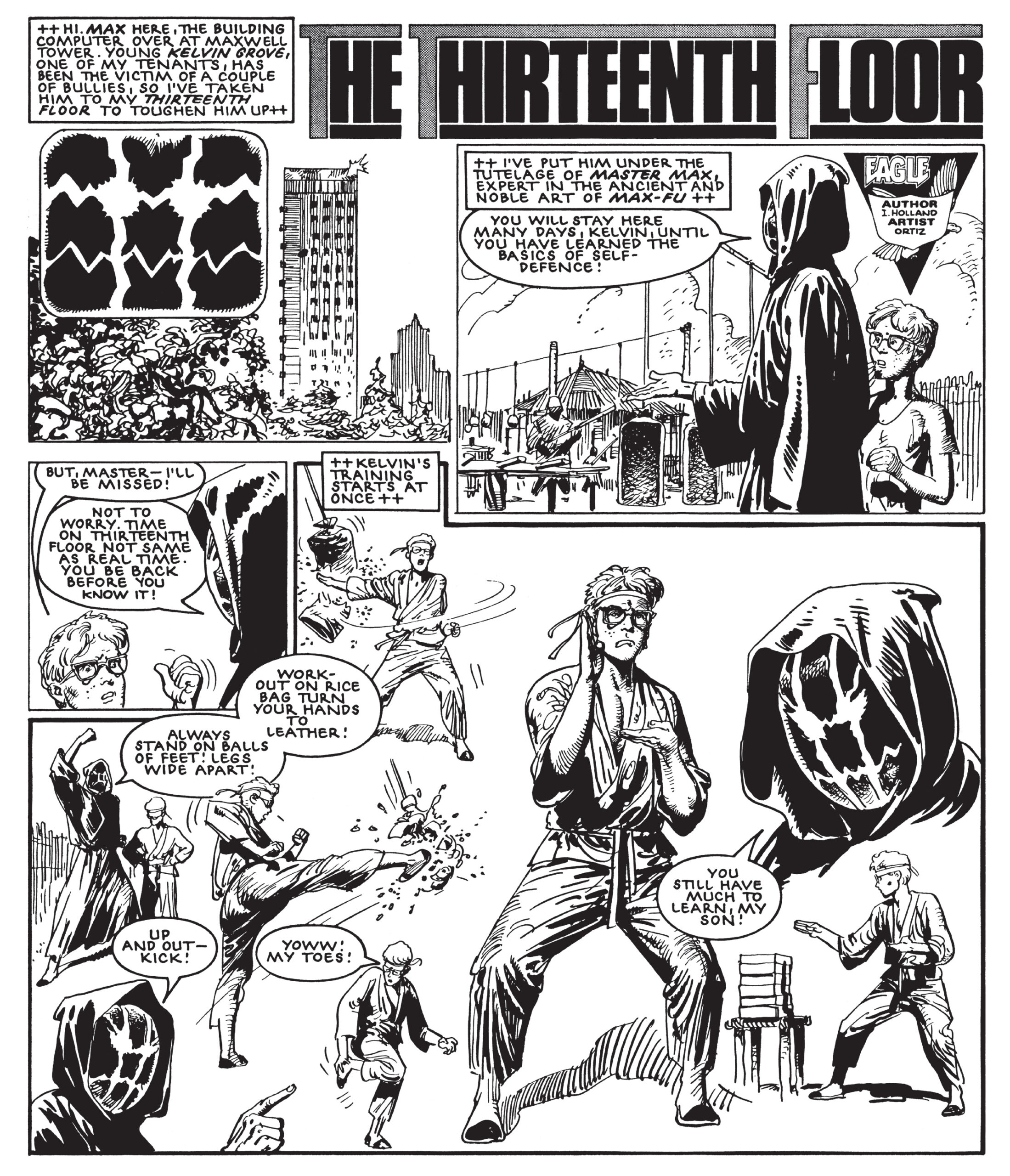

The third collection of The Thirteenth Floor, from John Wagner, Alan Grant, and José Ortiz, continues the terrifying adventures of Max, an all-seeing computerized apartment custodian who traps anyone who bothers his tenants in his terrifying thirteenth floor where “anything can happen.” On this floor (which technically isn’t supposed to exist in Max’s building due to the old superstition), Max creates computerized realities that play on his victim’s fears until they swear off their bad behavior forever.

The surface level horror of the strip lies in the horrific punishments that Max dreams up for his victims, but the deeper horror lies in the concept of an unsupervised computer serving as violent disciplinarian. Max doesn’t seem to have much human feeling, beyond the fact that it makes him happy to protect his tenants’ wellbeing. We can’t even really see him, though he can very clearly see us. He exists where no one can reach him, yet he makes decisions about who must be punished and how. Plus, no one really knows what Max gets up to except for his terrified victims, which means that he can’t really be stopped.

Clearly, The Thirteenth Floor leans into the “crime doesn’t pay” brand of horror— but only in a certain way and only for certain crimes. While it’s true that Max makes sure the criminals he brings to his thirteenth floor are frightened badly enough to never commit a crime again, Max never sees any punishment for essentially kidnapping and terrorizing people. In fact, his power and his daring only seem to grow over time. In this collection, due to some foreign interference, one of Max’s victims ends up dead. Unsettlingly, instead of being transparent about the death (which was not his fault), Max quickly arranges for the body to be disposed of.

Max can easily justify any action, no matter how grotesque, because he’s only justifying his actions to himself. This issue is heightened when Max’s programming becomes faulty, and the cheery helpfulness he regularly directs towards his tenants is replaced with malice and cruelty. He even nearly kills his friend Gwyn by causing him to fall off the side of the building.

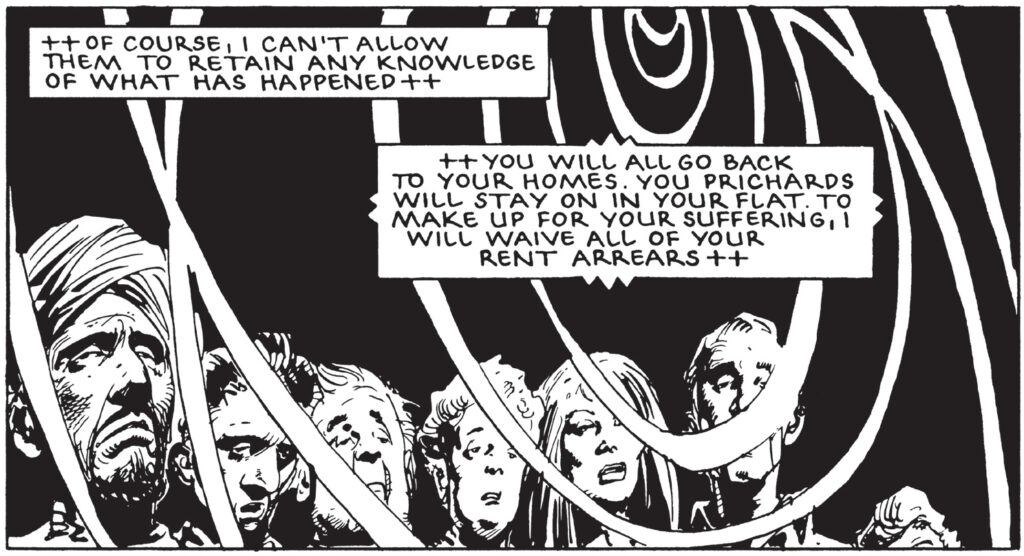

Meanwhile, the other tenants have been meeting secretly to discuss Max’s new behavior. They’ve turned off the cameras in their apartments, but Max, with the help of a neighbor, is still able to listen in on their plans. When they see Gwyn fall off the building and rush to check on him, Max traps them on his thirteenth floor, declaring, “Treason, I call it! But don’t just take my word— we’ll let the court decide.” Of course, this court, like all of Max’s courts, features only Max as the judge, jury, and executioner, and he brutally forces confessions out of each innocent tenant.

Of course, the day is saved when Max is fixed right before he actually kills anyone. Yet Max, instead of making amends, immediately uses his technological power to wipe everyone’s memories, declaring, “Of course, I can’t allow them to retain the knowledge of what has happened”. Max knows that if he’s held accountable for what he’s done, he’d likely be shut down forever, and so he must remain unaccountable.

What the third collection of The Thirteenth Floor reveals is that Max’s concept of what is right or wrong can change drastically and at any time, and that fact worries at the pattern of his punishments being doled out solely by him. Max is the perfect example of the dangers of a surveillance state and of a police state. He is all-seeing and all-powerful, but he cannot be seen nor acted upon. And most of all, he has situated himself as seemingly necessary for the happiness and safety of the tenants that he controls. He’s acting, not out of sadism, but on behalf of regular people who are being mistreated— the salt of the earth.

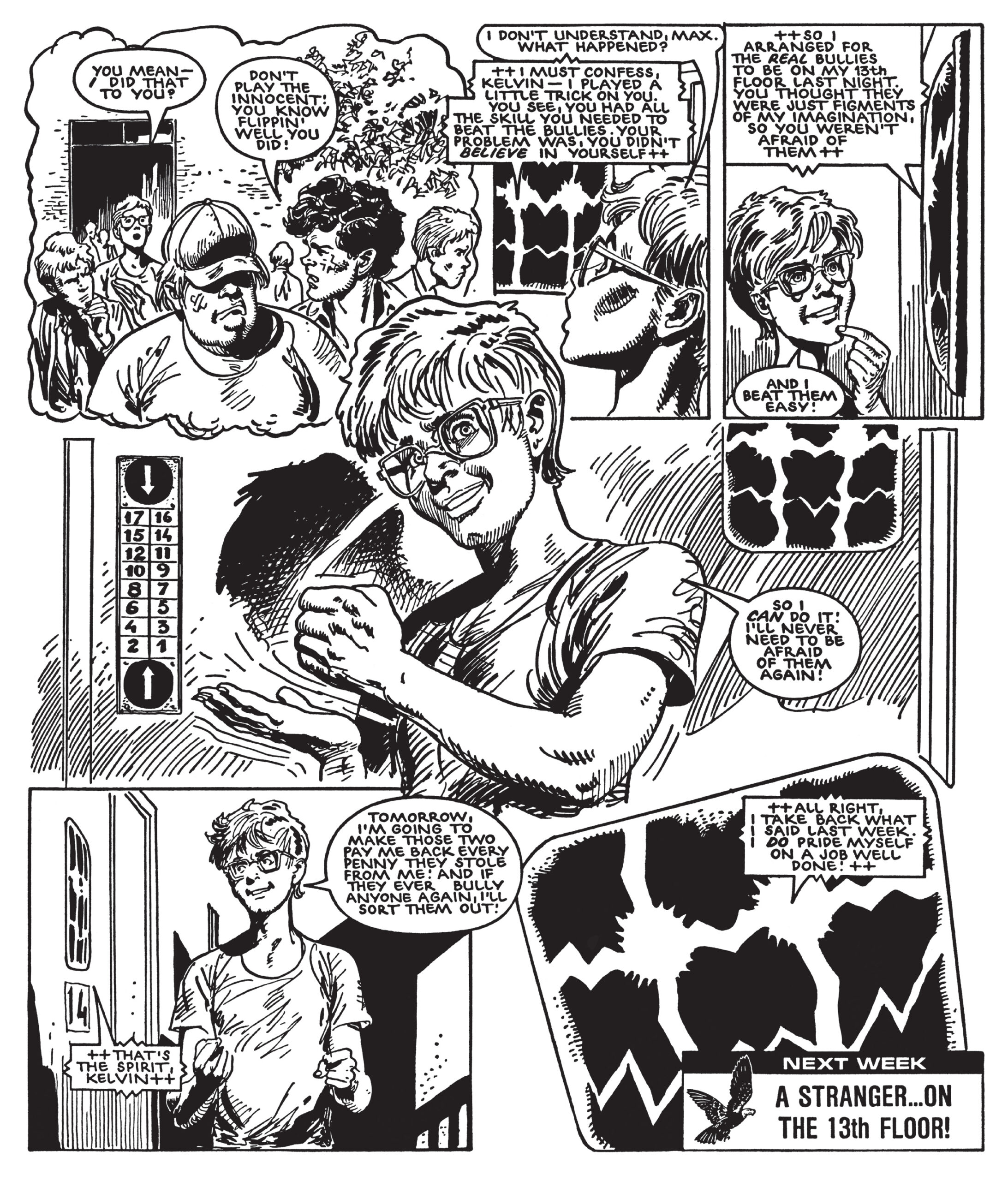

Perhaps the story that most sums up this manipulated dependency is one that breaks the mold of the regular Thirteenth Floor plot. When a young tenant named Kelvin is bullied by other children, Max brings the boy (as opposed to his bullies) to the thirteenth floor to teach him the art of “Max Fu.” After training, Kelvin is able to defeat his attackers in the simulation without much trouble, but when he sets off for school, he’s unable to defeat the real bullies, having forgotten all of his training in fear.

So, Max must step in again, this time applying his ingenuity more directly to the situation. Max convinces Kelvin to return to the thirteenth floor to train one last time, while, without Kelvin’s knowledge, Max draws in the real boys. Kelvin, believing he’s fighting a simulation, beats them easily and returns to school triumphant.

In Max’s ideal world, Kelvin can only succeed in overcoming his bullies with Max’s continued help. Kelvin alone, even with Max’s training, simply isn’t enough, because Max can only protect his tenants if they need his help. The story that Max has presented serves as a direct contrast to the “if you teach a man to fish” maxim. Teaching a boy to fight isn’t enough. Max must be involved every step of the way.

He wants to be all-powerful, and to do so, he must be relied upon. He must be trusted. He must, at least a little, be feared. And if the circumstances don’t fit his narrative, he will go out of his way to change them so that they do. Because, of course, the all-seeing, all-powerful computer who is only here to serve and protect knows best, and everyone knows that he only has his tenants’ interests at heart.

Tiffany Babb is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic. You can find her cultural criticism in PanelxPanel Magazine, The AV Club, Paste Magazine, and The Comics Journal and her poetry in Third Wednesday Magazine, Rust + Moth, and Cardiff Review. Her first book of poetry A list of things I’ve lost is forthcoming from Vegetarian Alcoholic Press Dec 2021. You can follow her on twitter @explodingarrow and sign up for her monthly newsletter at tiffanybabb.com/puttingittogether

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.