“Deadly elegant” – the sinister, spellbinding style of Jumeu Rumeu

10th November 2021

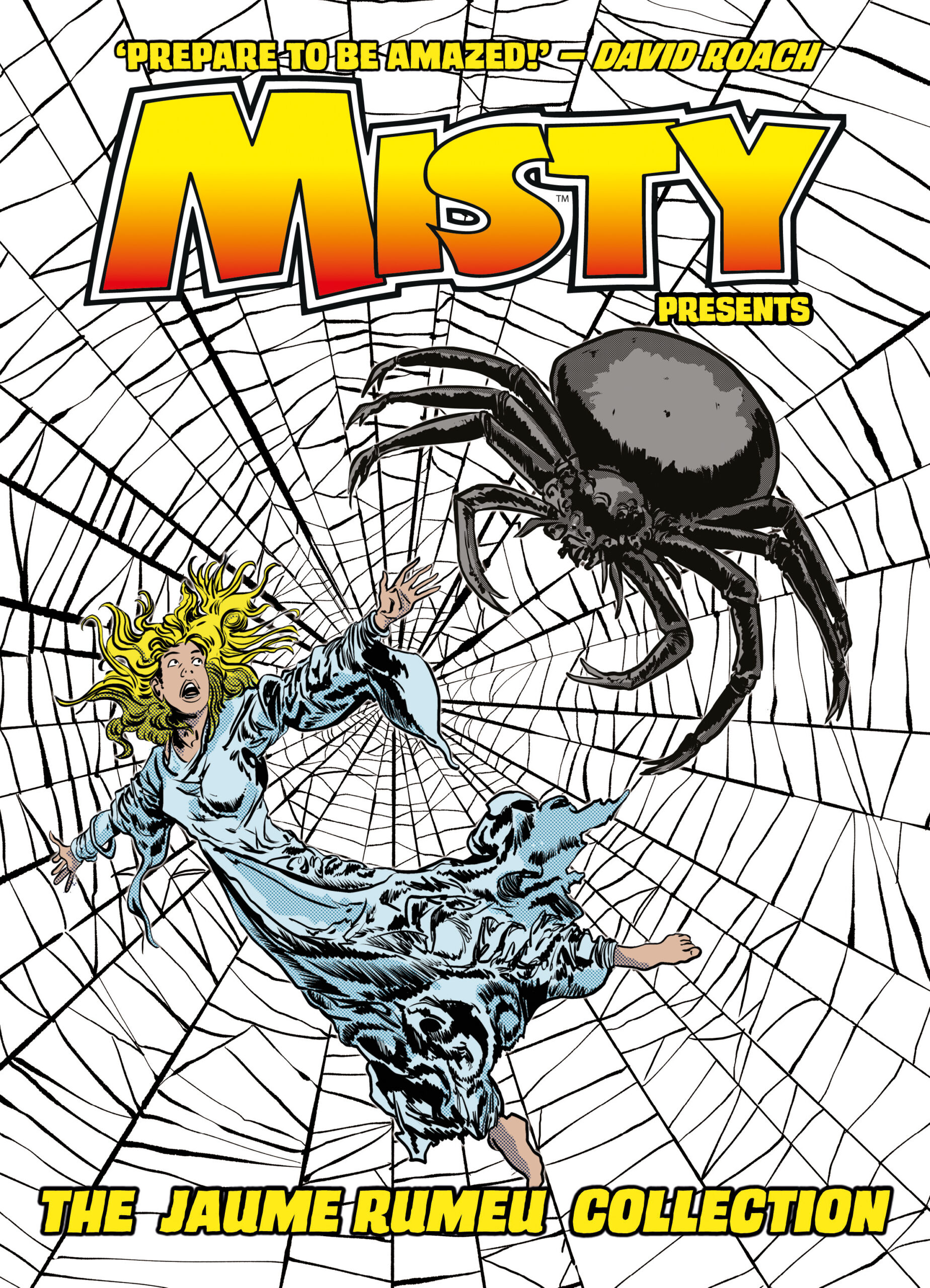

The Jaume Rumeu Collection is out now, with four terrifying tales from the pages of the legendary Misty by this overlooked Spanish master artist.

Continuing our series of short essays commissioned from selected comics critics that explore 2000 AD and the Treasury of British Comics’ latest graphic novel collections, Claire Napier discusses femme fatales, fashion, and and Jaume Rumeu’s spellbinding art…

“A raging femme fatale with killer style and a bone to pick with the British establishment” – who can’t relate to that? If you’re tragically square, and need further convincing to give this book a spin, let me weave you a welcome to this new set of Misty reprints.

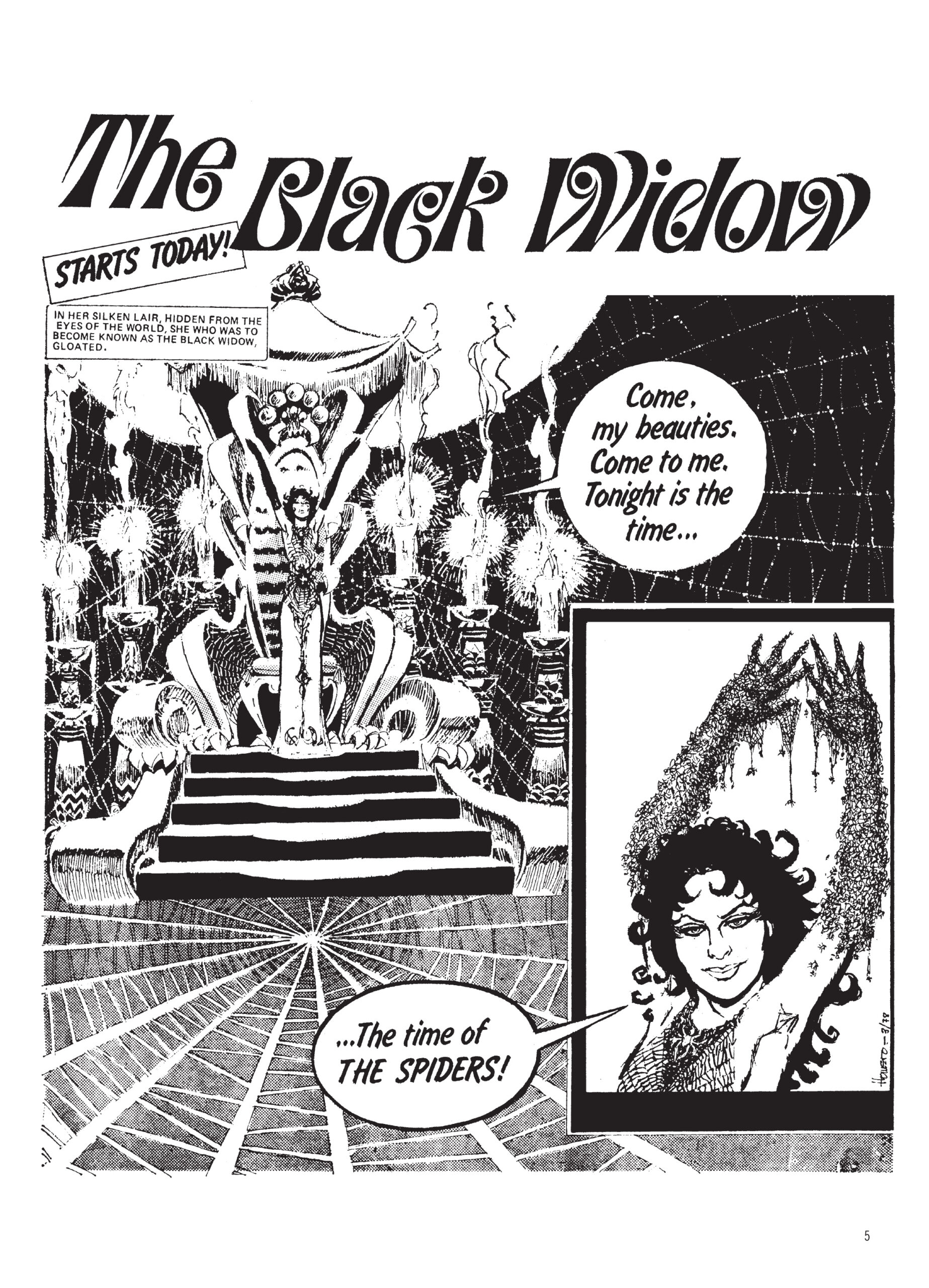

Unlike other Black Widows we might mention, the Spider Woman of Misty’s ‘Black Widow’ claims the narrative for her absolute own right from the jump by acting as a hostess. She’s a promise and a threat: the story may begin in a small, ordinary way, in a girls’ school science class, and go no further this time than the roads outside our heroine’s homes, but glamour and danger are coming. They’re guaranteed. The Black Widow is stalking her own story—a fine choice to add presence and authority for the girls, and other.

‘The Black Widow’starts strong, with all the melodrama and venom you can expect from girls’ media or media about girls: the threatening, deniable, fictional sexuality of the spider woman and the interpersonal texture of strict school discipline; the spite between girls forced into close, fairly closed community. A rowdy, dark-haired girl, Freda, feels inferior to a sensible simpering blonde, Sadie, who, more’s the worse, appears to bear her no malice. Rumeau’s art, like many of the Spanish artists working in British comics last century, and like many comics artists generally, is intimate where he can get away with it (a nipple-specific breast profile here and there, for example), and the character designs for both girls, the Black Widow, and even their science teacher are idealised to standards of desirability. They take turns in being in various amounts of thrall to each other, and of desperately needing to protect each other. The girls, though rivals, discover solidarity in the face of persecution—from groomers, from parents and teachers who don’t understand, and from bullying peers.

“I need no one to show me out, my sweet,” says “Mrs Webb,” dangerous spacewoman Black Widow in disguise as a rich and lovely lady, cupping schoolgirl Sadie’s face. Freda’s curls, in close proximity, call to mind the sapphic over- and undertones of similar moments in the British career of Marvel’s Kitty Pryde that locked in so many long-running readers in the 80s. Oh, no, attractive danger! And it’s being really nice to me!

But don’t worry. The Black Widow is only giving Freda and Sadie special necklaces and hypnotising them into framing out the crowds and appreciating beauty whence, before, they saw it not… because she’s really upset that her husband died. No further reason than that. Except that she’s “so far round the twist that she oughta be locked up.” Just normal lady reasons.

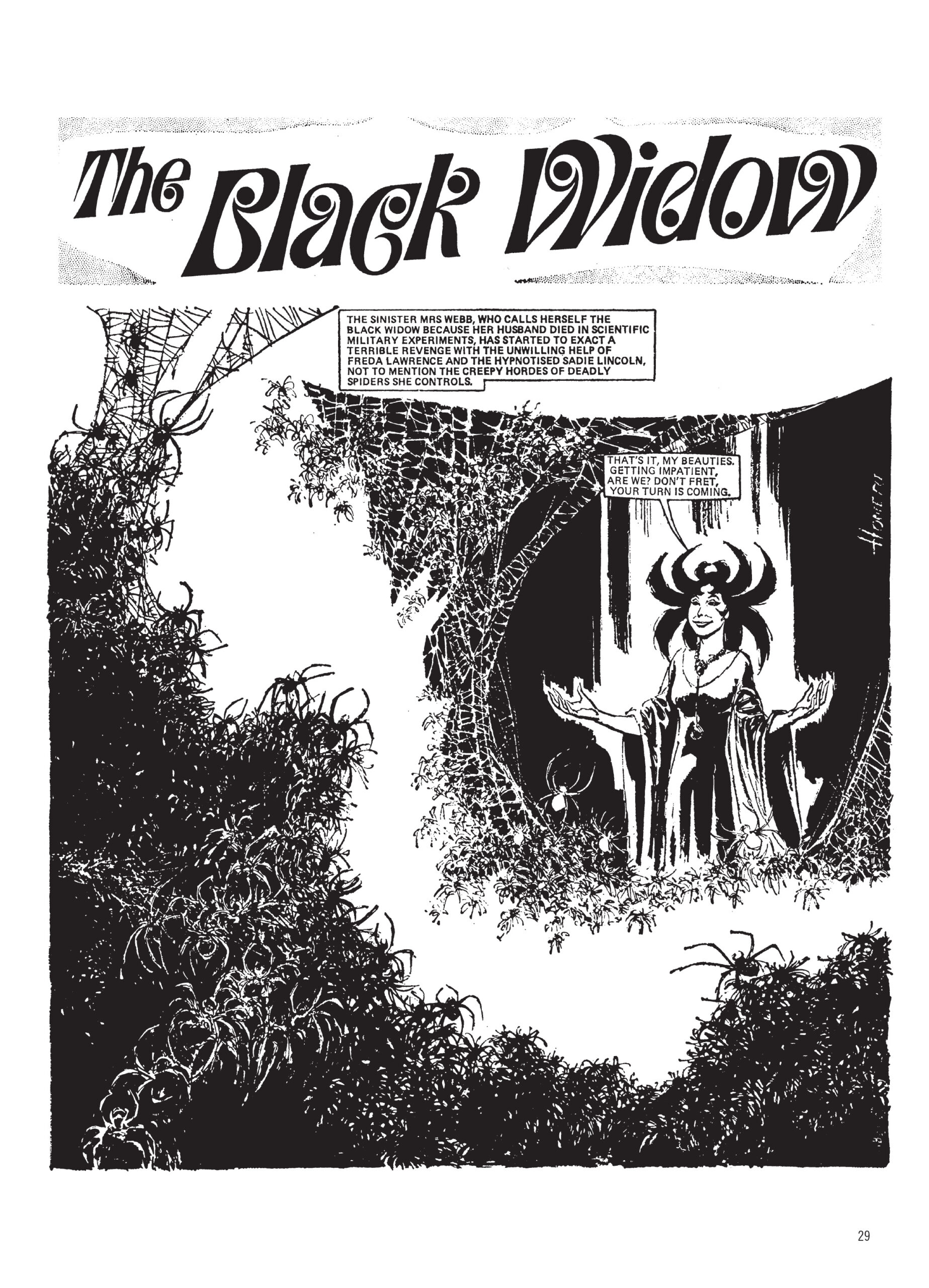

In his foreword, David Roach says Rumeau has “a gift for layouts, decor and architecture”‚ and it’s true, the Black Widow’s lair is a Phibesian confection, a place you want to hang out. But really, “decor,” “architecture”—just say fashion, darling! This is Girlsville, it’s not a taboo here. The Widow’s spider silk halter neck dress with crotch-level spider decal is deadly elegant, her opera gloves heightening the drama and echoing the spot black of her big, outré, gimmick hair. Her pre-raphaelite gown with padded cuffs and spider-girdle is a dream. Is that velvet? It must be velvet. Let me get a closer look… She entices through the luxury and detail of her fashion narrative. Rumeau makes her jewellery look heavy enough to lift—so tactile! John Miers’ essay in the back of this book, about theme in texture, will provoke further agreeable thought.

Sadie’s late seventies Safari/Disco debut ensemble is a kick, getting across her studious, practical, scientific nature along with a generally atmosphere-inducing aspirational glamour. A girl who tucks her trousers into her knee-high boots can’t be all stick-in-the-mud. And Freda’s rougher, more casual style—jeans, fewer modesty layers when she wears a v-neck or open-necked shirt—reminds us that she’s the more streetwise: the one who’s going to say “pay us” when the scary lady asks if she can have their spider, and finally figure out Mrs Webb is a phoney. I was brought right out of the story to think “should I buy some clogs with a high arch?” when a pair dominates a panel so their owner might squash a spider. You could say this was lost readership, but consider its original format: Misty was a magazine with four-bag chapters of this story. The longer you could draw out your reading that week, the better. Inducing a little wardrobe daydream is, in fact, adding value.

Longrunning cultural scripts are visible even here, in Misty, the comic for girls who liked living on the gothic edge. Freda, notably long, lean and thin, says she’ going to earn money from selling the Space Spider Sadie found instead of “laying round here getting fat.” Just a throwaway line of mundane, we-swear-it’s-true horror fiction—getting fat is corrupt (no it’s not) and it could happen to you—to, today, distract from the more studied horror of being caught in a giant spider web with your rival, inside of a derelict house that’s probably haunted. It’s supposed to be naturalism, the kind of thing that girls say and mean, and of course it was—but it didn’t have to be, and might not have been so much if it weren’t replicated in entertainment, and by men making that entertainment, whose business it is not.

Bill Harrington’s script is a little odd. It gives the impression that it was created art-first, with Rumeau drawing a good-looking sequence of panels and Harrington creating dialogue and captions to go over the top of those—or perhaps of there being some disconnect due to language difference, Rumeau being Spanish and Harrington, presumably English. Dialogue sometimes suggests that a scene is going one way, and then suddenly course-corrects to match what is happening in the next panel. The original implication, that the spider Sadie finds in the first chapter is from space, is moved decisively over to make way for a plot about revenge on the military and advanced radio electronics. It doesn’t spoil the fun, or detract from the impeccable atmosphere of frustrated glamour and restricted, big-dreaming adolescence. It’s just an interesting window into a world do wondering about exactly how it was that weekly production of comics used to be a genuine, scrappy, lifestyle-supporting industry in Britain, instead of the hold-out domain of an organised few. Another window, perhaps less welcome, is the old school lettering throughout. Words are (typewritten?) and squeezed into squared-off, retro-television-shaped boxes with wonky spacing, cramped leading and no modern plasticity, nothing to imply tone or enhance mood. I revel in its staid awkwardness, because I grew up reading this style of comic and consider it an aesthetic value of its own… to me it’s a cultural comic book Britishness that’s revealing and familiar. It’s not “good,” but it is indicative, if only of the fact that everyone agreed it was good enough!

In ‘The Black Widow’, Rumeu’s faces value even arrangement of features, heavy lashes outweighing 30s-throwback brows, and the high-contrast implication of blemish-free, porcelain skin, but despite the restrictions that places on the movement of facial muscles (can’t draw a frown if forehead lines are illegal) he does manage to create a range of interesting, readable expressions. Sadie squints towards the sky having seen a mystery comet, and her upturned, narrowed eyes and slightly open mouth convey a sense of focus, internal preoccupation, that allows her to feel human and real even if she is a goody two-shoes.

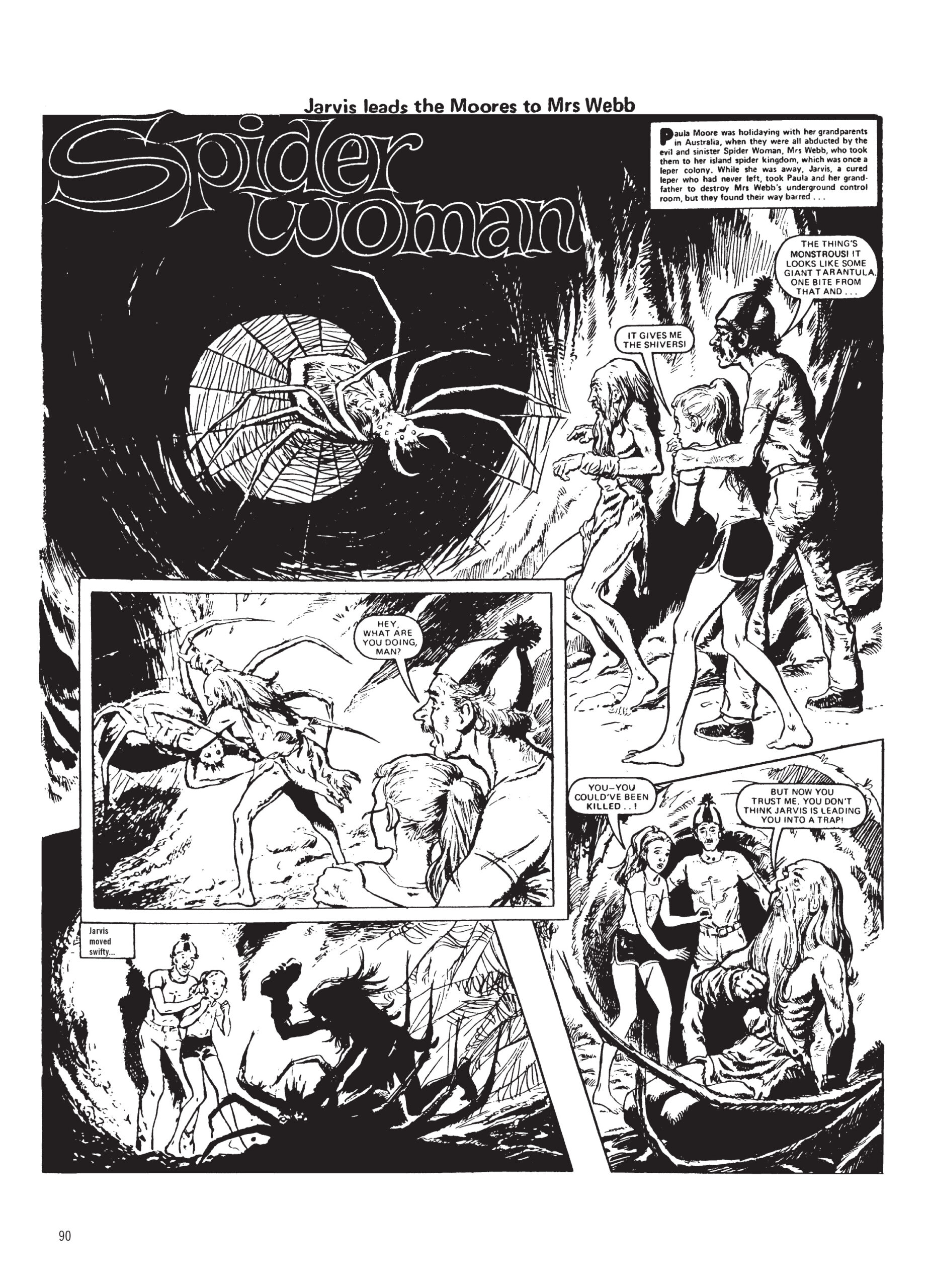

Unfortunately—fictionally speaking—the Black Widow is foiled by the courage and mutual support of Freda and Sadie before she can kill the Prime Minister. Her hold over them is dissolved, and the creeping yuckiness of her evil, radio-controlled spiders recedes. Until… The Spider Woman! A year or two later, the team gets back together, for a second tale of terrorism against a good, nice girl. This time Mrs Webb gives us a little Corto Maltese cosplay, amongst the banana leaves and bamboo huts of an island shipwreck, and Raume draws grandparents enough for it to really register that restricting his art to youth-obsessed facial minimalism is a loss and a shame.

His Black Widow — ‘Spider Woman’ — is different, almost looking designed for animation, with less interest visible in his rendering of her wardrobe. The two stories together really make for an interesting artistic comparison. The book is worth picking up for that alone—the adventure, peril and pluck of these stories, and the following, classically-toned horror anthology shorts, just a bonus.

Claire Napier is a comics critic and editor, with cartoonist coming in a struggling third. She spent nine years in critical editorial at WWAC and is now a freelance editor who works with independent creators, optimising their projects and helping their voices rise. Find her at clairenapier.com

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.