Kevin O’Neill 1953 – 2022

7th November 2022

Everyone at 2000 AD is devastated to learn of the death of artist Kevin O’Neill.

Words like ‘unique’ and ‘genius’ are not uncommon in the pantheon of 2000 AD creators, but no-one deserves them more than O’Neill, whose innovative, iconoclastic, idiosyncratic, inventive, visionary, and provocative work still has the ability to shock and dazzle, even decades after its first publication.

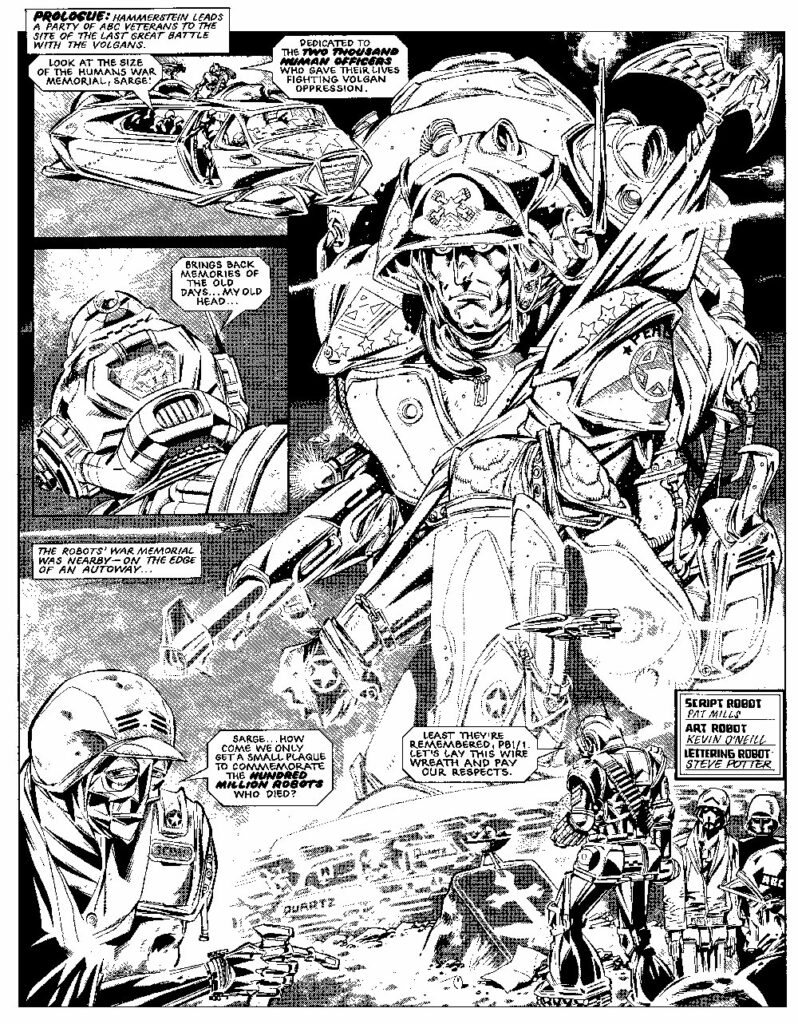

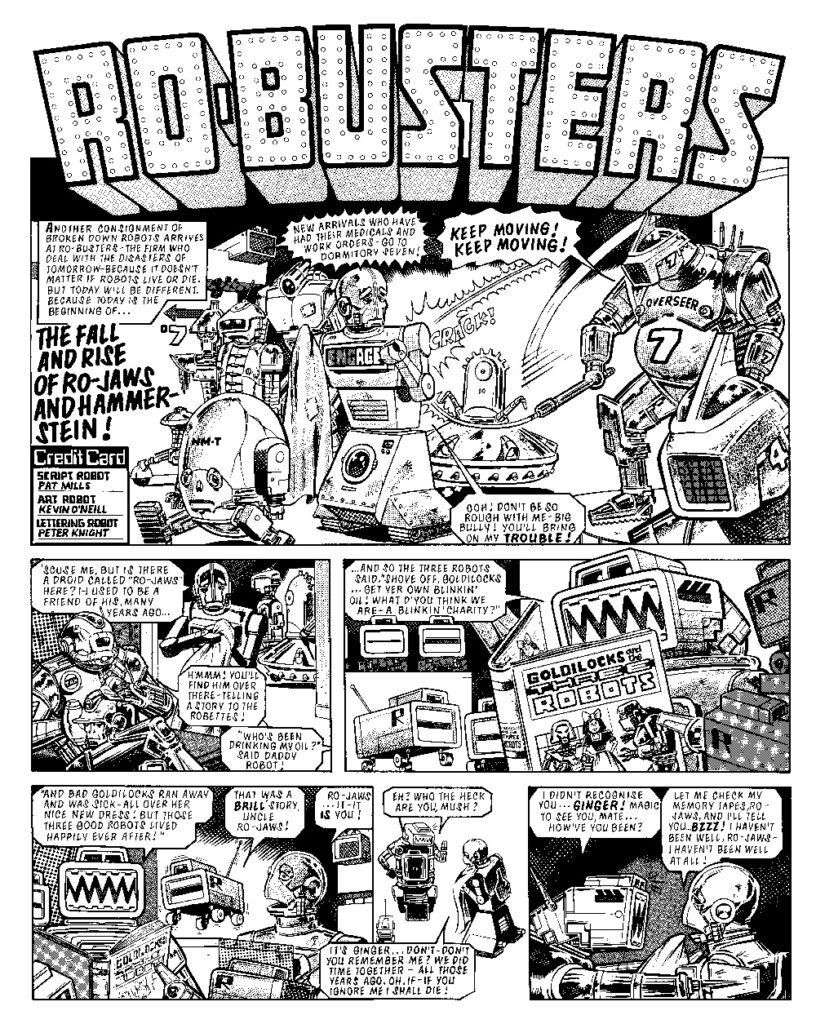

The co-creator of Ro-Busters, A.B.C. Warriors, Nemesis the Warlock, Metalzoic and Marshal Law with Pat Mills, and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen with Alan Moore, O’Neill was one of the most important and unique artists British comics ever produced. From the towering, Gothic bacchanals of Nemesis to the anarchic, razor-sharp and emotionally-brutal work on League, O’Neill’s art was the scourge of conservative editors and was blacklisted by the Comics Code Authority in the US for being ‘objectionable’. There are so few artists – even at 2000 AD – that have been so uncompromising in their style, a style so visceral, so extreme, so individual. And, even now, you simply still cannot mistake O’Neill’s work for anyone else’s.

Born in 1953 on a working-class council estate in the south London suburb of Eltham to an English father and an Irish mother, O’Neill was an avid reader of British stalwarts The Beano and The Dandy before being introduced by a school friend to MAD magazine, whose panels crammed with anarchic, satirical humour, sight gags and comedic grotesques would be a profound influence on his work.

Forced to give up the offer of places at art schools in London after his father retired early, O’Neill became an office boy at IPC under the wing of art editor Janet Shepheard, who would go on to design the iconic original logo for Judge Dredd. ’I handed out soap and towels to the editor once a week, spent time leafing through old volumes of comics, and gradually doing minor art and lettering corrections and pasting up reprints of Billy Bunter strips,’ he told George Khoury in True Brit. ‘Jan was a good, if strict, teacher. She also told me while looking through my samples that it would be ten years before I was good enough to work as a professional artist – and she was right!’

After a few years freelance, O’Neill returned to IPC and eventually becoming assistant art editor on 2000 AD, the new science-fiction comic being developed by Pat Mills. Alongside Shepheard and designer Doug Church, O’Neill helped define the early look of this new title, his sharp, febrile lines, postmodern design sensibility, and mischievous sense of humour giving it a fresh, spiky and iconoclastic edge that spoke to the moment amid the simultaneous rise of punk and its DIY fanzine scene.

Most importantly, frustrated that creators were not receiving the attention they deserved, O’Neill was instrumental in 2000 AD adopting credit boxes that, for the first time, named the creative teams on each individual strip, including letterers. Virtually unheard of in the close-knit world of British comics, where publishers always feared writers and artists being poached by the competition, O’Neill convinced the censorious senior editor Bob Bartholomew that the boxes were merely experimental. They have remained ever since.

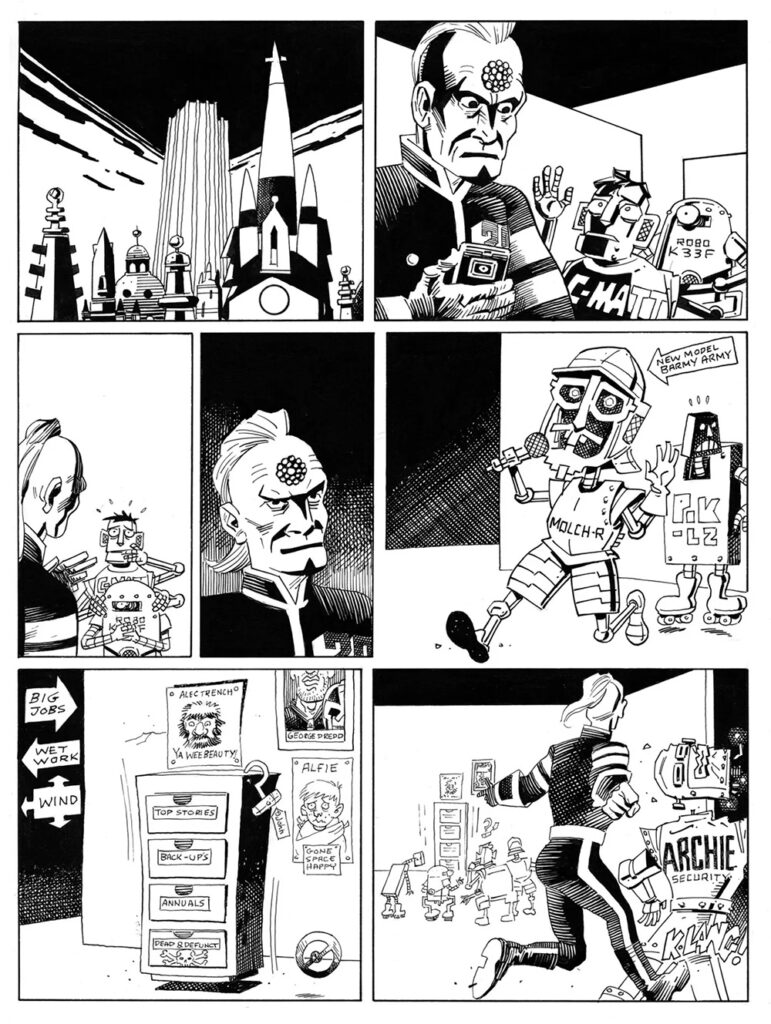

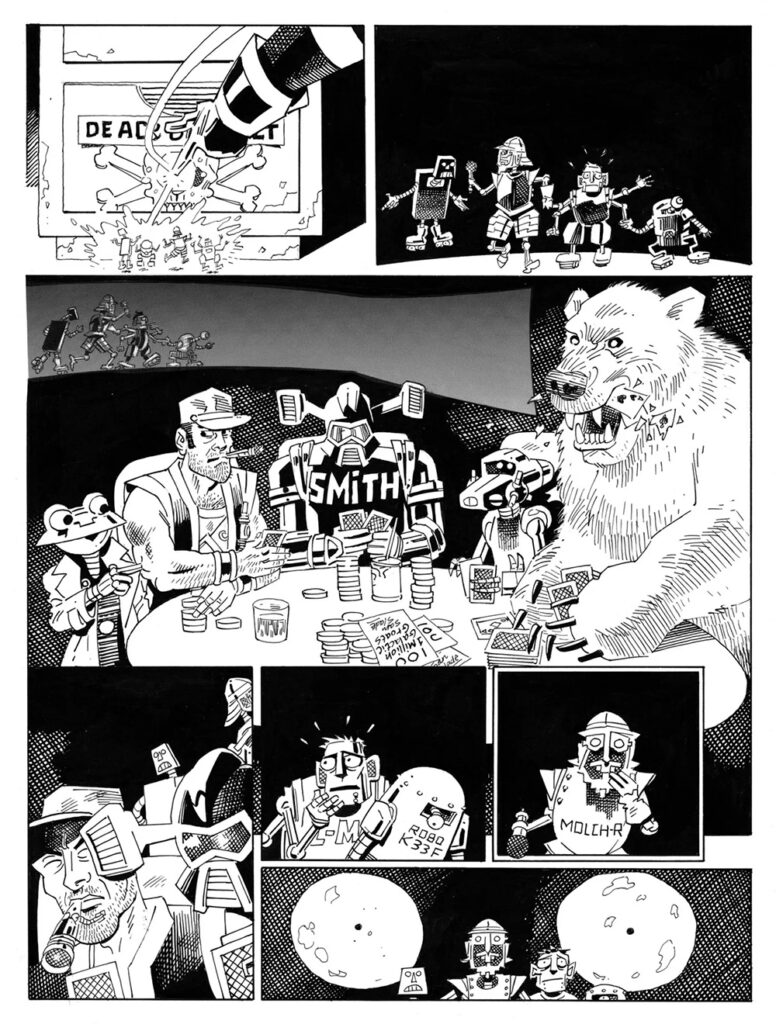

As well as designing Judge Dredd’s obsequious robo-servant Walter the Wobot, O’Neill designed the principal characters in Ro-Busters, a strip about a robot rescue squad – ‘an inhuman International Rescue’ – that Pat Mills wrote for Starlord, including characters such as Ro-Jaws, Hammerstein and Mek-Quake, who went on to be a part of the popular A.B.C. Warriors strip after Starlord merged with 2000 AD.

His other artwork for 2000 AD included parodies, such as the anarchic and scatalogical take on Godzilla – Bonjo from Beyond the Stars – and Flash Gordon parody Dash Decent. Shok!, a one-shot sci-fi horror story co-written by editor Steve MacManus, was later copied wholesale by the makers of the film Hardware, with the producers eventually agreeing to credit and pay the creators.

But it was after leaving IPC – following an argument over the violence in Harlem Heroes sequel, ‘Inferno’ – and becoming a full-time artist that O’Neill’s distinctive talent truly came into its own.

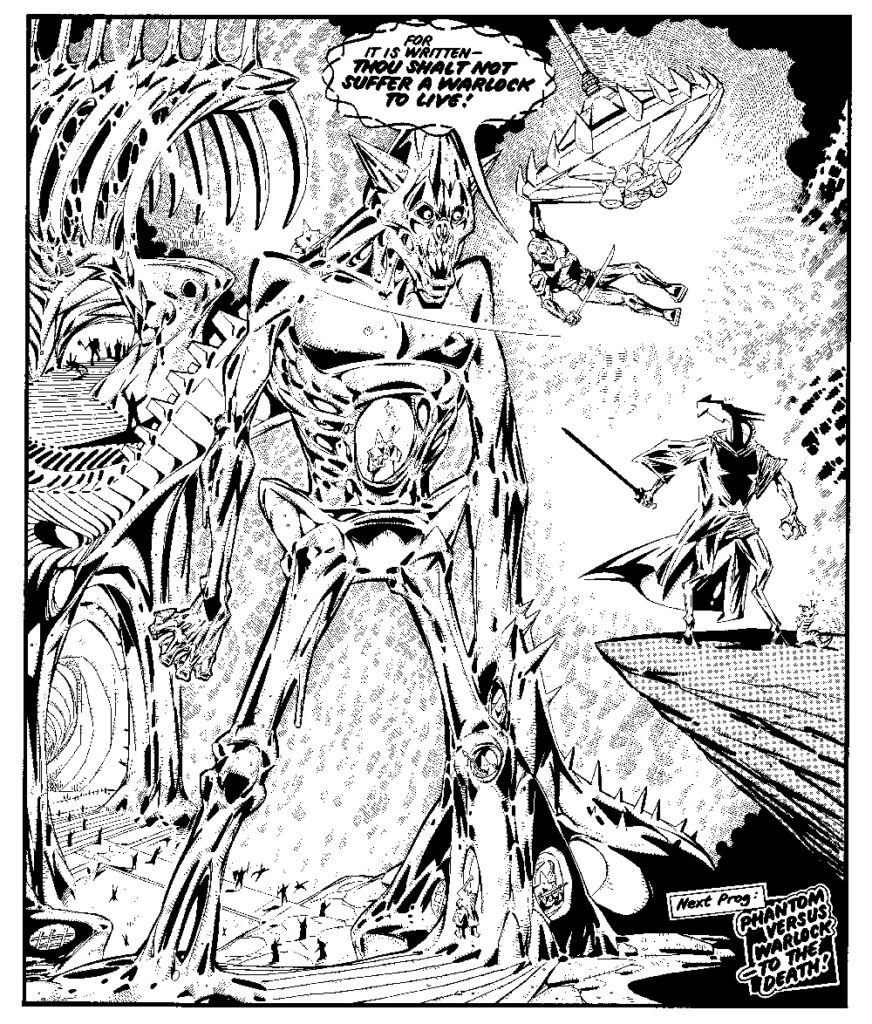

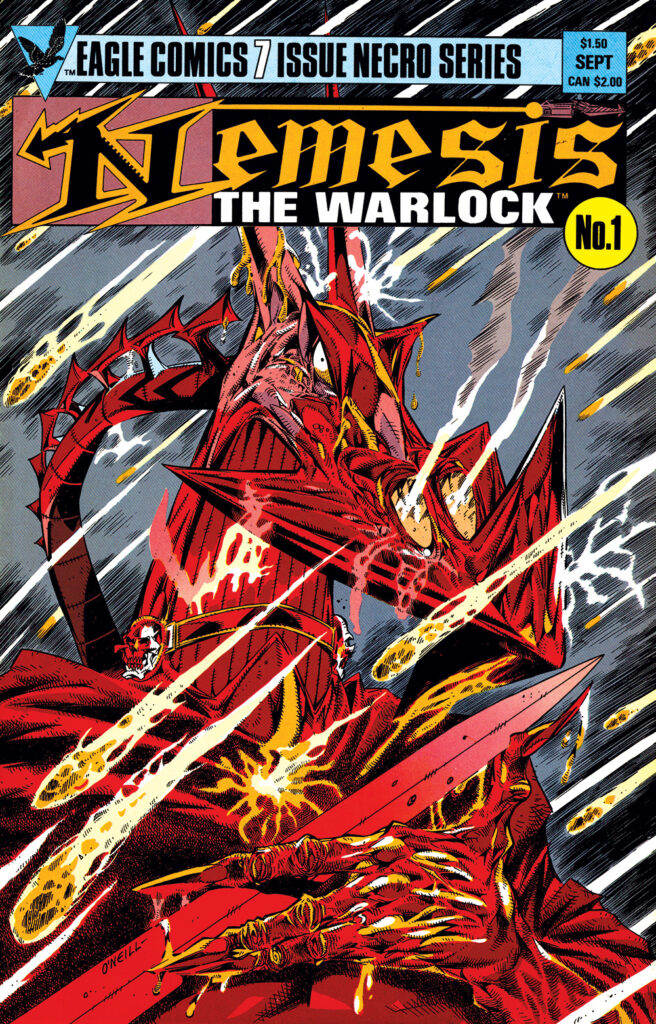

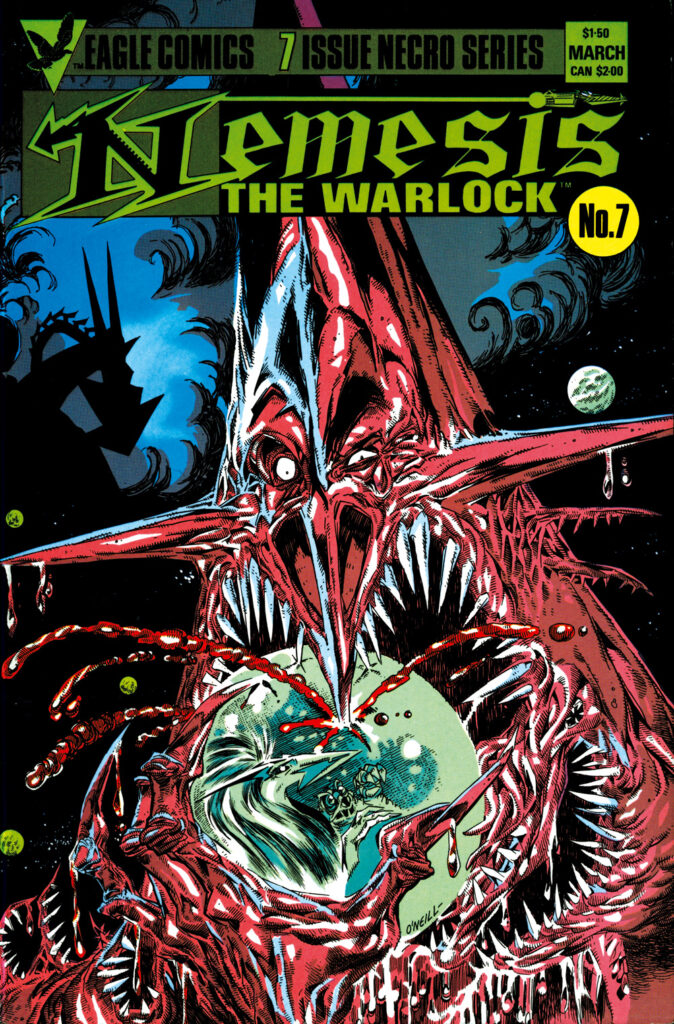

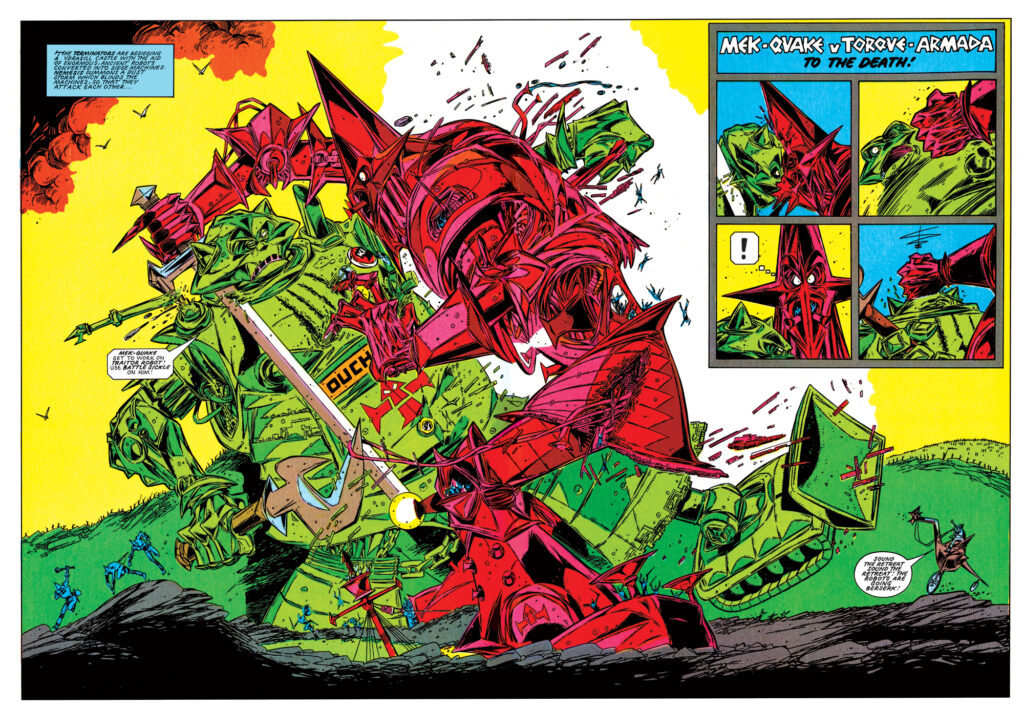

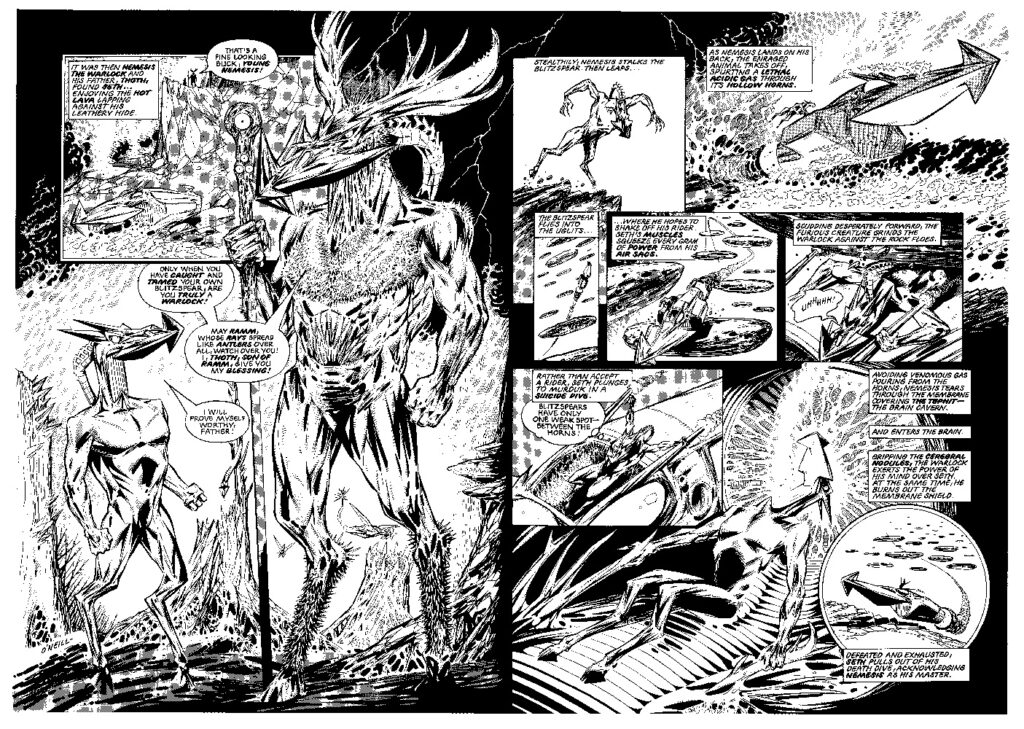

Nemesis the Warlock was a magic-wielding, cloven-hoofed alien freedom fighter who battled the xenophobic, fascist interplanetary empire of the bigoted human leader Torquemada, whose mission is to purge the galaxy of ‘deviant’ alien races. With its blend of brutal satire and anti-establishment anger, Nemesis quickly became one of the most popular recurring characters in 2000 AD. Mills and O’Neill’s Catholic upbringings produced a strip seething with iconoclastic fury.

Under O’Neill’s pen, Earth was transformed into ‘Termight’, a hellish dystopian hollowed-out planet of gravity-defying tubular highways and stalactite housing blocks like something from a medieval nightmare, but splattered with off-the-wall humour and details more befitting a Heath Robinson drawing; Nemesis and Torquemada duelled amidst Gothic towers, along penis-shaped bridges (later amended ever-so-slightly to evade editorial censorship), across time and space, and eventually to the end of the world.

O’Neill was eventually forced to leave the series due to financial pressures but returned to draw the final ever episode of Nemesis in Prog 2000.

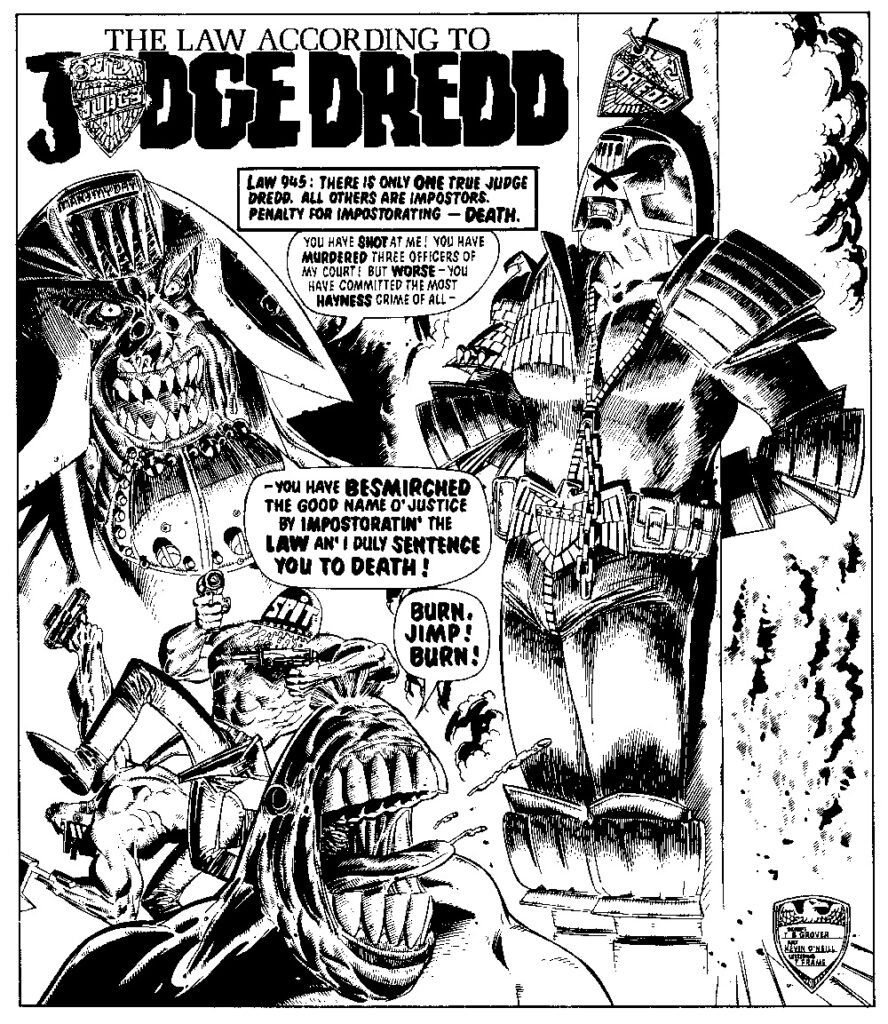

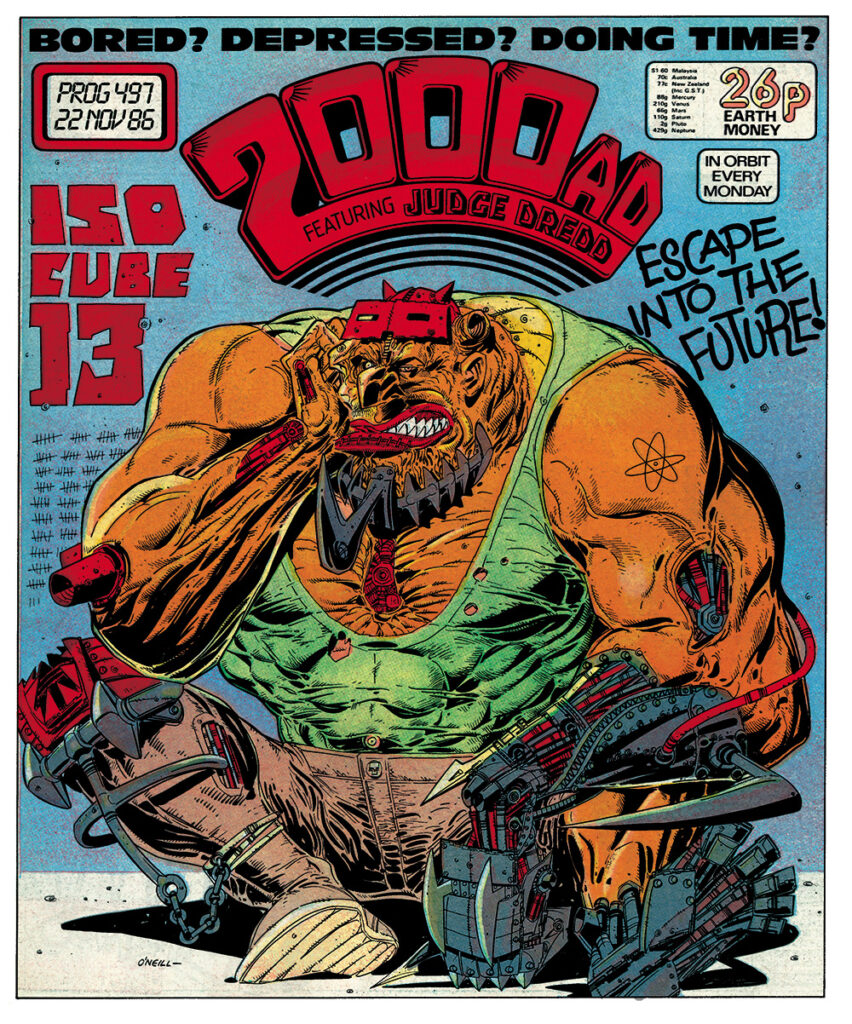

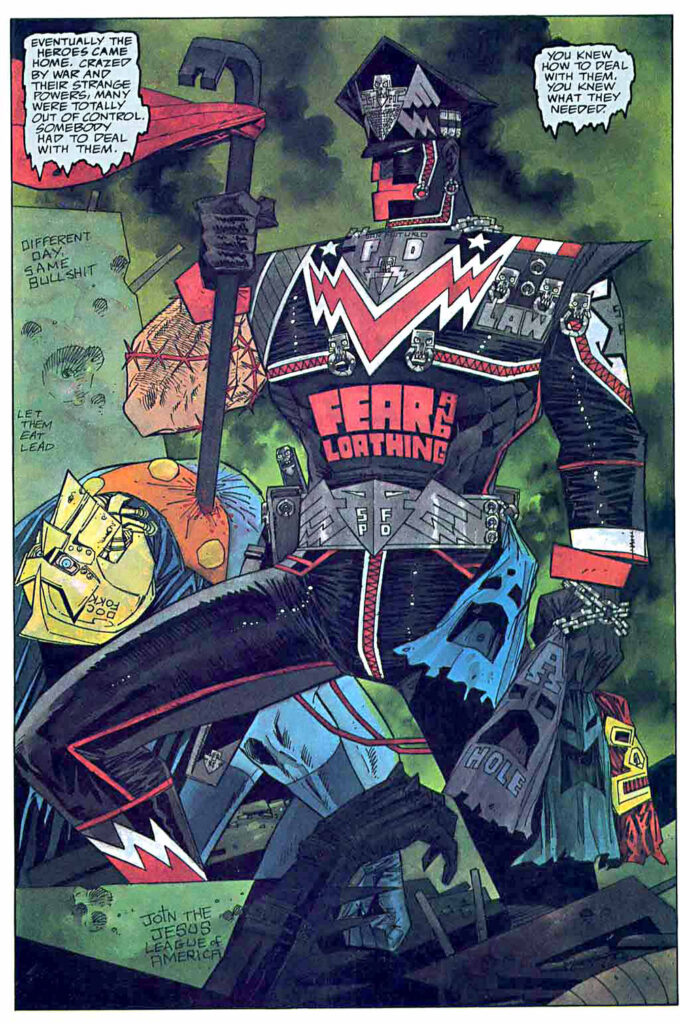

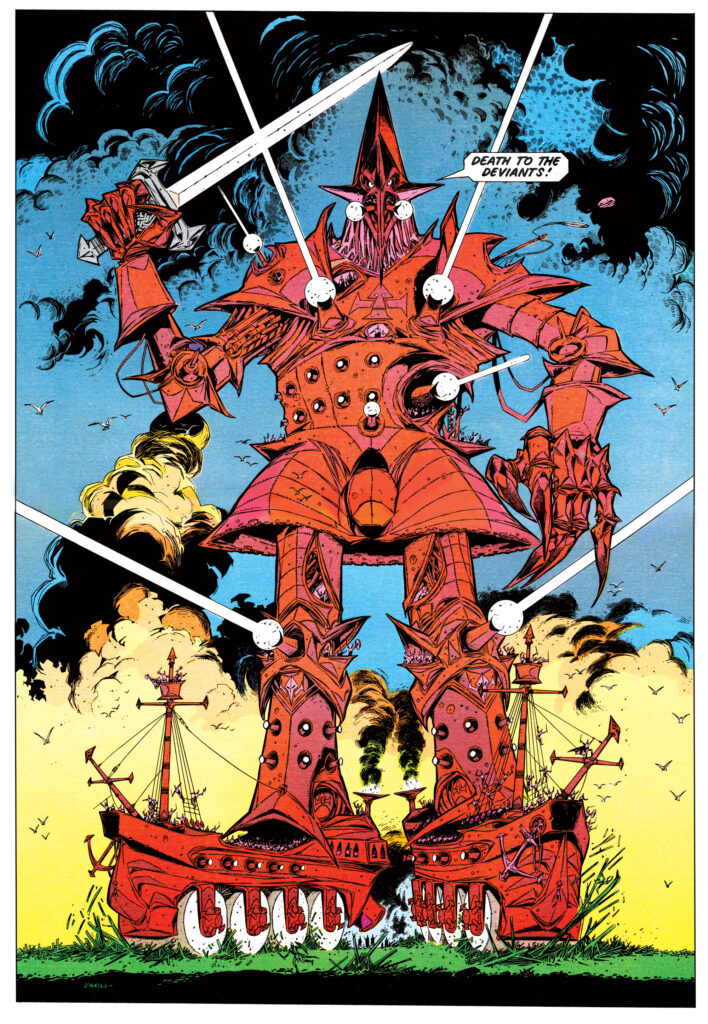

He also worked on disturbing Judge Dredd stories such as ‘The Law According to Dredd’ and ‘Varks’, before co-creating Metalzoic with Mills. Published as a colour DC graphic novel in 1986 and later serialised in black and white in 2000 AD Progs 483-492, this highly-acclaimed series pitted robot apes against robot mammoths on a future Earth, with just two human characters, and produced the memorable cover to Prog 485 with the insane Armageddon announcing ‘I operated on my own BRAIN!’.

Part of the charm of his work were the in-jokes and self-deprecating humour he peppered throughout his pages, inspired by the work of his favourite Mad magazine cartoonists. Often behind on deadlines and struggling financially, he portrayed himself in Nemesis as a hunched over monk, chained to his desk as he is chastened by the spirit of Torquemada: ‘You’re taking too long on the illuminated borders, Brother Kevin! Your bestiary must be finished this century!’

When DC Comics began scouting for British artists in early 1984, O’Neill was amongst those who became known as ‘The British Invasion’ but the twelve-page tale in 1986’s Tales of the Green Lantern Corps Annual, resulted in self-appointed US comic moralists of The Comic Code Authority condemning his style wholesale as ‘objectionable’. It was later printed in an annual, minus the authority’s mark, but despite a moral victory of sorts, O’Neill’s work never fitted into the mainstream of American comics, though he worked on Lobo, Bizarro, Death Race 2020 and the mischievous entity known as Batmite with Alan Grant.

However, his wider reputation is founded on two strips that both suited and encouraged his iconoclastic style.

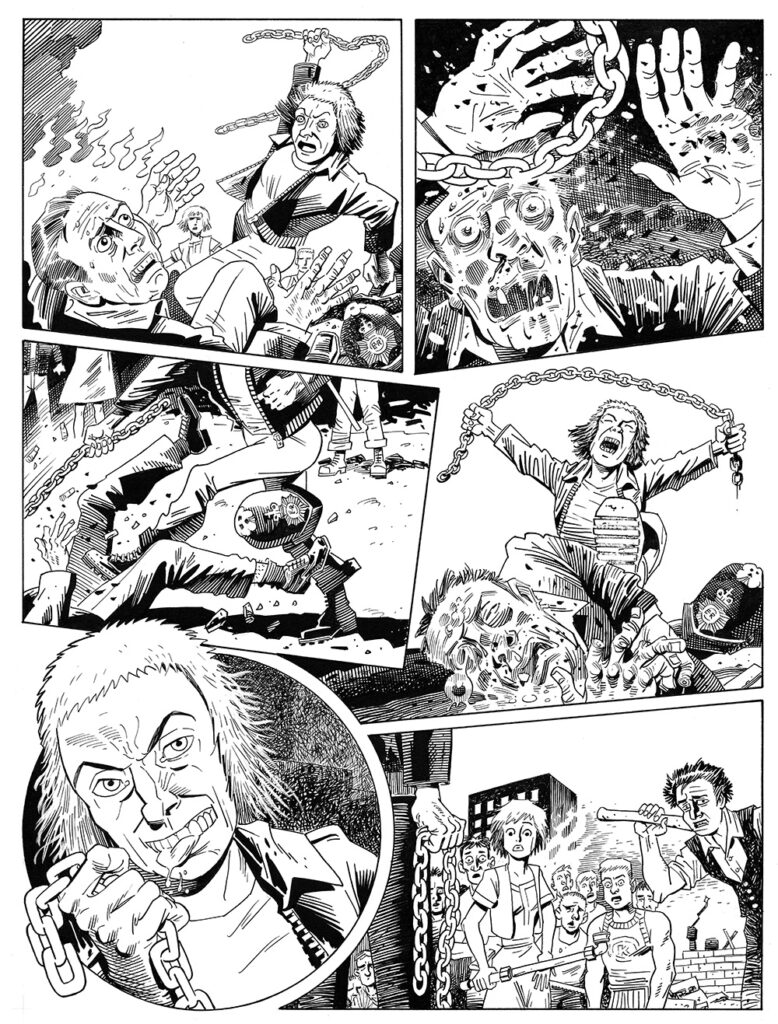

Pat Mills’ searing satire on superheroes, Marshal Law, followed an ultra-violent government-sanctioned superhero killer. First published by Epic Comics in 1987, the character briefly shifted to Toxic!, a creator-owned title launched in 1991, before moving to Dark Horse Comics. This heady mix of extreme graphic violence, sex and brutality, and a deep vein of dark humour, is still intoxicating and represents the anarchist wing of the British deconstruction of superheroes of the 1980s and ‘90s.

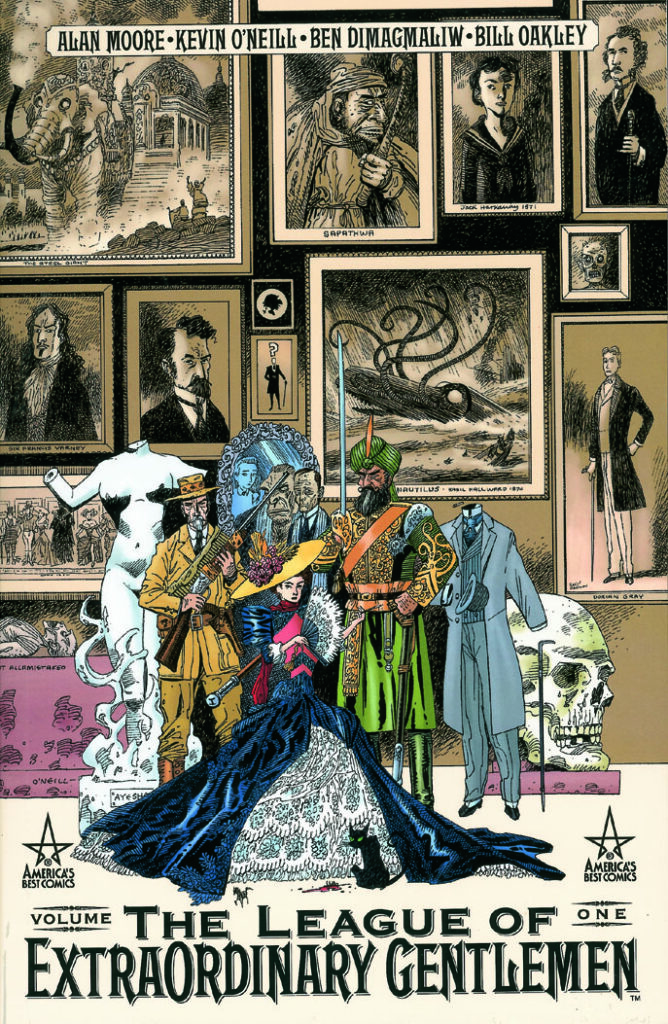

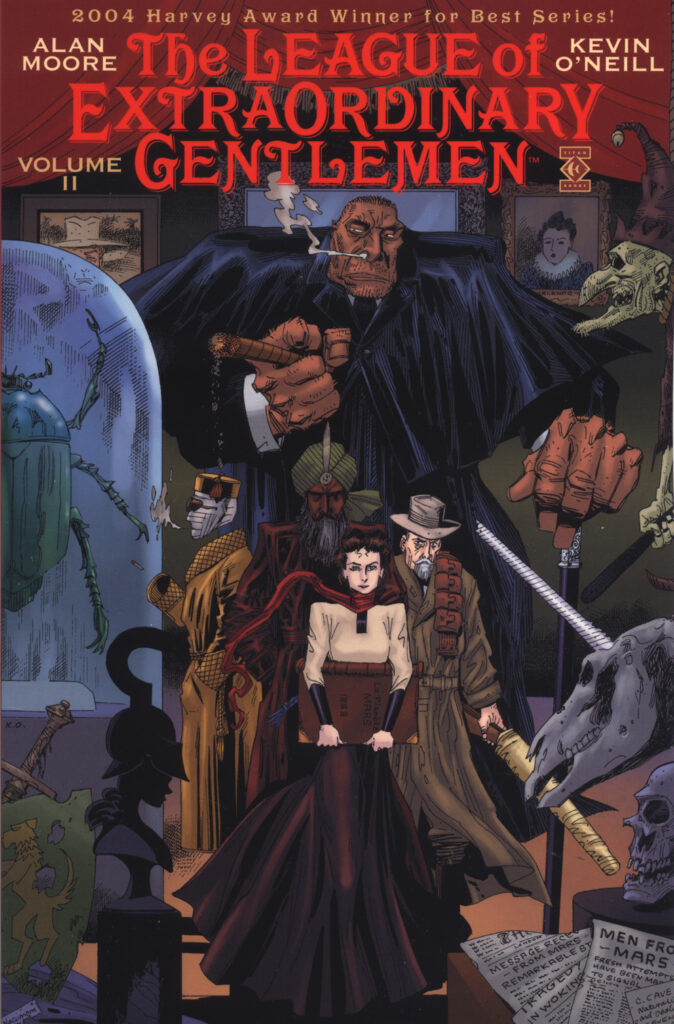

It was The League of Extraordinary Gentleman, written by Alan Moore, that sealed O’Neill’s fame and legacy. Set in 1898 in an England where the great characters of Victorian adventure fiction actually exist, League became enormously popular (despite the poor and badly-received Hollywood adaptation) in no small part to O’Neill’s art. Having drawn the cover to Moore’s first foray into music, a single released by the ‘Sinister Ducks’, O’Neill had contributed covers to the Titan collections of his 2000 AD ‘Future Shocks’, but with League their strengths reinforced each other in a sprawling, hyper-detailed and at times enigmatic collision of words, art, and design. ‘Partly because of Kevin’s art, we can span comedy, horror and pathos in a couple of pages,’ Moore said in The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore. ‘Often in one page, sometimes in one panel. The emotional range that Kevin’s artwork lends to the story is fantastic. It’s one of the main assets of League.’

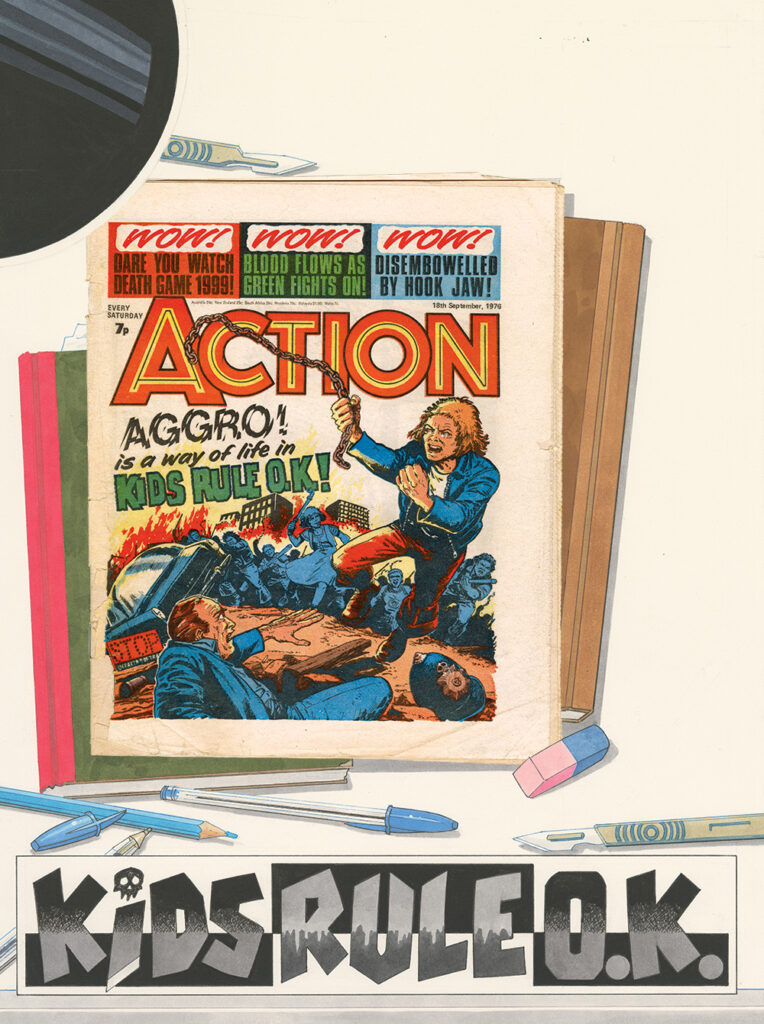

Following the conclusion of the series, O’Neill enjoyed a return to 2000 AD of sorts earlier this year when he and Garth Ennis revived the infamous ‘Kids Rule OK’ strip from Action, 2000 AD’s controversial predecessor, for the Battle Action special and his final work, the return of ‘Bonjo From Beyond The Stars’, will be published in 2000 AD at Christmas.

Kind and incredibly generous with his time, O’Neill possessed a warmth that belied the ferocious anger and gleeful violence of his work, with him wielding his pen like a scalpel and creating art that possesses a profound beauty made up of harsh, sharp edges.

‘I suppose I have a kind of parallel life,’ he said on the Barbelith website. ‘I don’t have any suburban friends at all. I’m great friends with a band called Rockbitch and I have a lot of occult friends and friends who work in the sex industry. I suppose my benign smiling face might just conceal an appalling secret life!’

His art challenged and changed, provoked and delighted, he was the anarchic, gleeful humour of British comics twisted and twisted to breaking point, rendered in a style that was grotesque and beautiful at the same time. ‘I’d hate to see all comic art streamlined into one awful branded style,’ he once said. ‘What a nightmare vision, the world having one big harmless dream.’

His death is a monumental loss for comics. Truly unique, truly a genius, O’Neill made art like no-one else could or will; we were richer for having known him, and poorer for having lost him.

Our very deepest condolences go out to his family, his friends, his colleagues, and all those who have been in some way touched by the magic of Kevin O’Neill.

The bestiary is finally finished. Rest well, Brother Kevin.