Still Angry After All These Years: Third World War in the 21st century

27th January 2020

With Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra’s Third World War being reprinted in its entirety for the first time, the Treasury of British comics has commissioned short essays from selected comics critics that examine different aspects of this seminal political series from the pages of Crisis.

Tom Shapira discusses the strip’s sense of deep-seated anger and asks whether this makes it even more relevant today…

In 1992 Francis Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man, a book which arrogantly predicted the final triumph of Western-style liberal democracy, and the capitalist ideology which guides it. There would be no more large wars, no clash of ideologies. It was the book for the 1990s, a decade in which cynicism and irony ruled with an iron fist – a world with seemingly nothing left to fight for.

Taken in that context it is little wonder that Third World War, published between 1988 and 1991,didn’t become the hit its creators hoped it would be: it was too political, too talky, too angry. Like its writer, Pat Mills, it was too much of everything for the 1990s. Third World War did not want to hear that all conflicts were over, it was a book that came out looking for a fight. Which means it’s probably just about right for now.

The series was part of Crisis, a spin-off magazine from 2000 AD meant to appeal to a more mature audience. While Crisis didn’t last long, its competition, in the form of Deadline, made it all the way to 1995. Deadline was young and hip, the herald of the 1990s. Strips like Tank Girl, Johnny Nemo and A-Men were violent and funny and took a boot to The Man with great style an air of ironic detachment.

This was ‘the problem’ of Third World War – it was not cool or detached. It didn’t want to make you laugh, it wanted you to stand up straight and protest and even riot. It was probably the wrong thing to ask of Generation X. Pat Mills, already part of the old guard of British comics by the time the story started, was always a passionate writer. His greatest strength was that no matter how disposable the strip was in theory, he seemed to take 100 per cent seriously as piece of art and social commentary. Hook Jaw, commissioned as a Jaws cash-in, was used as vehicle to condemn rich industrialists and their mistreatment of the environment; while the comedic Ro-Busters constantly had class issues on its mind.

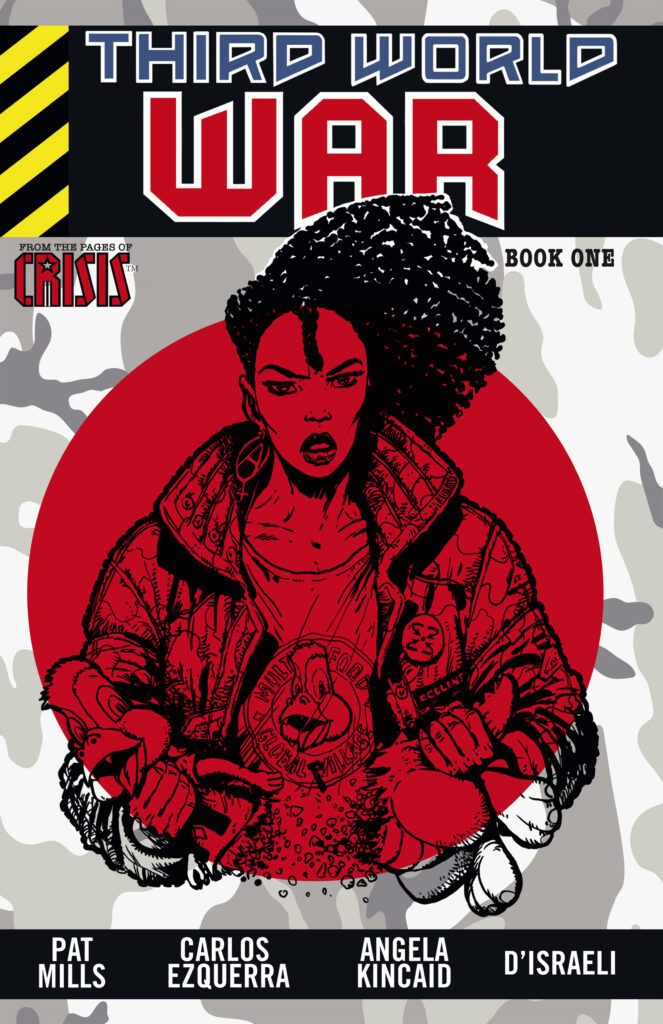

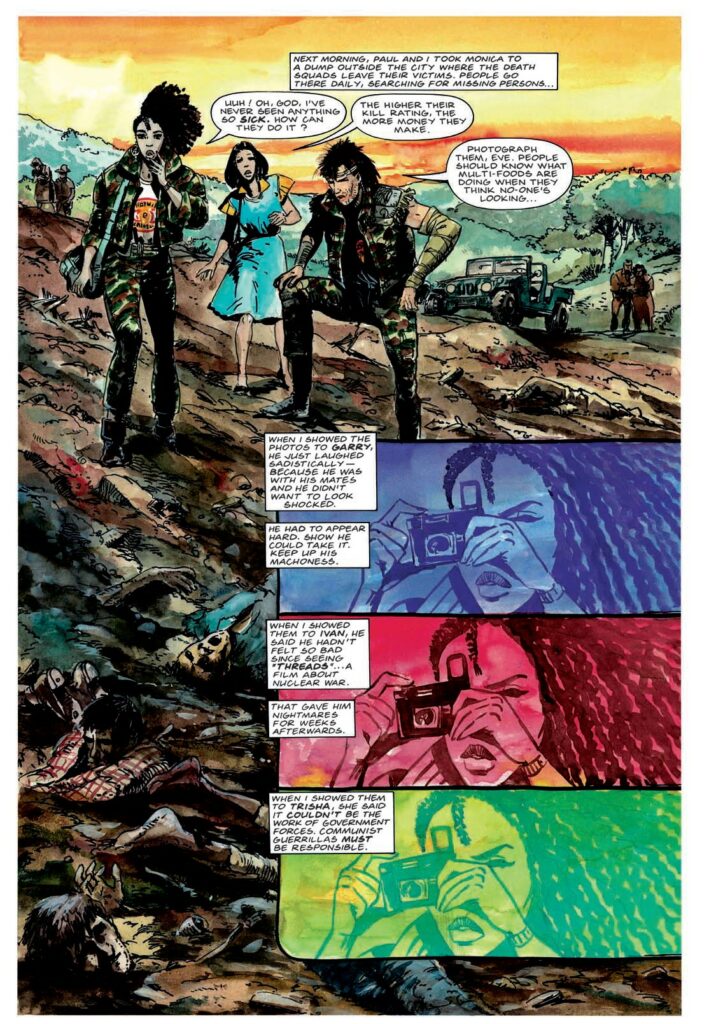

Third World War is Mills unleashed and unbound. Without the limitations of a young audience it gives us a story of the capitalistic oppression of a ‘third world’ country in the onset of the 21st century. Presenting the struggle in all its gory details, from death squads to forced resettlements, illustrated with an unusual baroque flair by 2000 AD mainstay Carlos Ezquerra (with occasional chapters by Angela Kincaid and D’Israeli). Yet the single fights on the page were not the limits of the book’s scope. Its main interest was in a wider discussion: what does it means when the first world ‘intervenes’ with the third; Cui Bono? Ask Mills and Ezquerra throughout the story. Answer – never the ‘peasants’, in whose name the fighting is done.

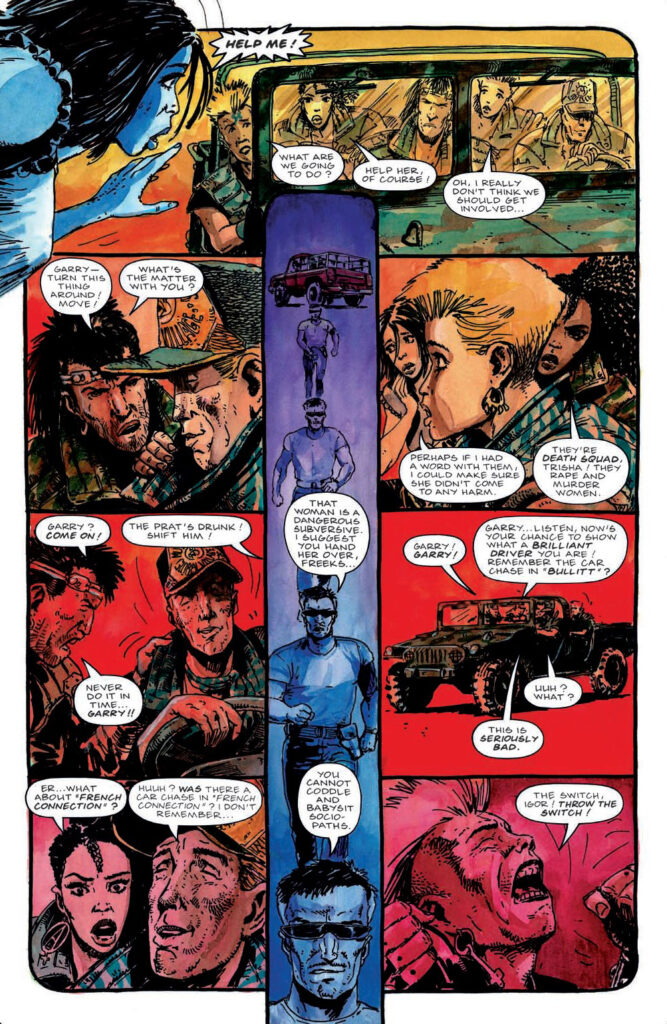

The plot of the story, revealed through the diary written by fresh recruit Eve as her unit is sent to “capture hearts and minds” an in unnamed South American country, allows Mills’ script a rare laser-focus. For a writer whose tendency has always been to attack the reader with an endless barrage of characters and concepts this is a work of singular vision: it knows the story it wants to tell, it knows the information it wants to explain and it knows how it wants its readers to feel at the end. Is it subtle? Of course not! Nor was it ever trying to be. This the type of comics George Orwell could appreciate.

The downside for all of this is that the script rarely allows the reader a moment of rest. Quite possibly this is the result of reading in a singular sitting what was meant for serialization, but even taking that into account there’s a certain lack of modulation throughout the story: it’s just a barrage of pain coming your way. Charley’s War, an earlier work written by Mills, also came with a similar bleak emotional tone overall, but changed its presentation between chapters – allowing the readers a moment of inspiration and elation before plugging them back into the horrors of the trenches. Nothing like that here. Ezquerra, of course, as the co-creator and one of the leading artists of Judge Dredd knows a thing or two about tuning the horrific into the entertaining.

It is Ezquerra who provides some of the most interesting bits of the story. Used as he is to high melodrama and big action moments, the script calls for many scenes of talking and emotional downtime. When you do get a rare action moment it’s unpleasant and ugly: you’re not meant to enjoy the baddie being blown away, or to snigger at a particular nasty brutalization. Still, even going against the grain Ezquerra remains a superb artist. If there exist a mythic ‘bad Ezquerra page’ I’ve never seen it.

There’s some standout pieces here that really seem to take Ezquerra to a new direction: one page in particular breaks into three sections with the middle one showing a single figure approaching our protagonist in the most threatening manner while they freak out as he comes closer and closer. Another bit, close to the ending of Book I, takes a moment that should be ridiculously on-the-nose and charges it with exceedingly creepy energy. The series manages to preserve Ezquerra’s typical professionalism, which made him such a peerless storyteller, while adding more complicated layouts and imagery.

There’s sadness to these characters, and the world they inhabit, that is expressed purely through the visual: like the way Trish is keeping a façade of cheerfulness, fooling herself enough to believe all is well as she performs one act of horror after another; or the look in Garry’s eyes the moment he first kills a man. Even the character of Paul, that the script over lionizes in a manner more fitting for typical heroic adventure series, is given some sinister edge in his movement and expression.

Stylistically it’s still recognisable as the Ezquerra we know and love, but there’s some added emotional burden here. The artist suppresses his tendencies for big and bold in favour of more downbeat presentation. This is Ezquerra drawing with the weight of the years upon him. This is as it should be. This is a story meant to make you feel that weight.

Thirty years after it ended Third World War now sees the light of day again. The faults are still there, but in the harsh light of the third decade of this century it seems everything that made the comics work, including the bloody single-mindedness, shines ever brighter. As we enter the 2020s it’s only appropriate for a new generation to find this old book – and get angry all over again.

Tom Shapira is a critic who has written for Sequart, Shelfdust, The Comics Journal and others. His book, The Lawman, a long-form appreciation of the first Judge Dredd story, is set to be published by PanelXPanel Magazine.

Third World War is available now in paperback from all good book and comic book stores, online retailers, and the Treasury of British Comics webshop in paperback and limited hardcover editions.

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.