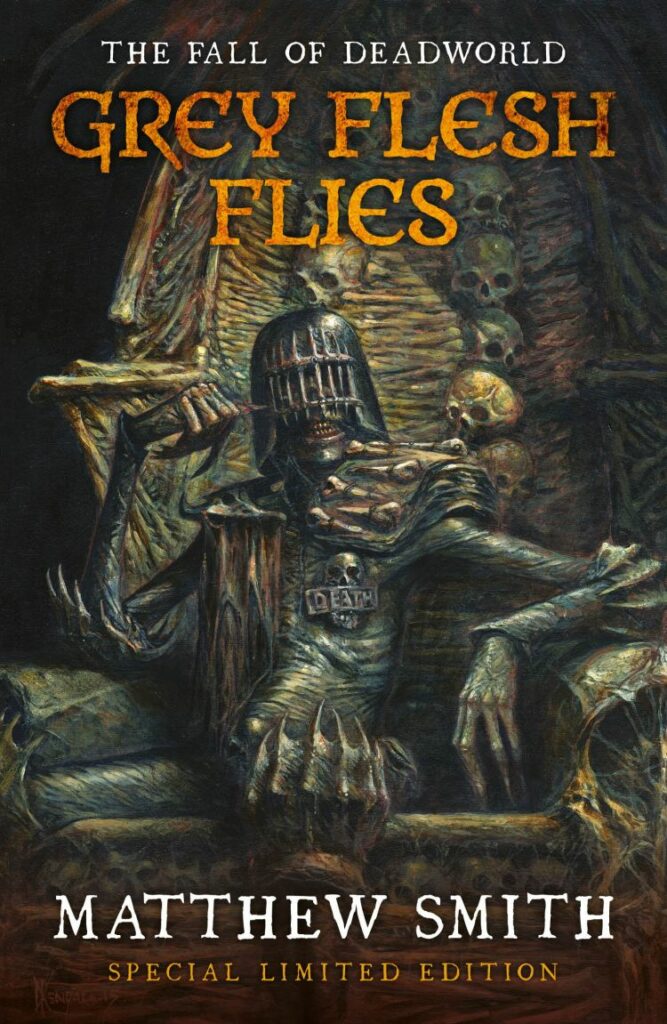

The end is getting ever closer in the latest novella in the acclaimed Fall of Deadworld series by Matthew Smith – available to order now!

Choose from ebook or Kindle editions, or buy one of only 200 copies of a special edition paperback.

The end of the world is pretty damn nigh … but it ain’t over yet! Misha Cafferly and Judge Hawkins are still on the road, still somehow breathing after all these months, and they’re damned if they’re giving in now. There’s hope on the radio. But the soil is poisoned, the water is foul, the bugs have become killers, the greys are everywhere, and now the terrible Sisters are even turning the survivors’ own minds against them… Time is running out.

Buy limited print edition now >>

Buy ebook >>

Buy for Kindle >>

CHAPTER ONE

The world was incrementally dying; there was no doubt of that now. Bit by bit it was dropping away into darkness, slowly and steadily. There hadn’t been an atomic flash that had exterminated millions in an instant or a seismic shift in the tectonic plates that had cracked continents in half; instead, it was deteriorating in stages, like a once healthy organ being eaten from the inside out. You were aware of it in the sudden sharp scent of corruption brought by the wind, in every fluctuation in the miasmic light, and especially in how the plant-life was responding to its new environment, contorting horribly like it couldn’t understand what was happening to it. It made your heart break to see it, Misha thought; the flora was adapting with no comprehension to what was going on around it, once verdant shoots twisted by a poisoned earth to the point where they, like everything else on the planet, could no longer survive.

She was standing on a ridge looking down at a copse, and the trees were virtually petrified, noticeable for their sickly calcified brittleness. Considering the season—she was fairly sure they were somewhere in the summer months, but it was increasingly difficult to discern the passing of the days, as a tombstone-grey cloud settled permanently over the sky—the branches should’ve been bursting with leaves, but instead they’d been reduced to skeletonised shadows of their former selves. They hunched together like terminally ill old men, bewildered by the malicious toxicity of their situation, and as they struggled to maintain that pulse of life, the cancerous new eco-system was ensuring their eventual downfall. She imagined it wouldn’t be long before fissures appeared in the bark, the trunks would split asunder, and the trees would collapse as little more than ash. Misha and Hawkins could pass by this way again in a week, and the landscape as it was would simply be a memory. She didn’t want to come back, though; partly because retracing their steps would be one more sign that they had nowhere to go, and partly because she had no desire to witness such grim inevitability. Better to leave it in the rear-view mirror, decaying out of her sight.

She glanced across at Hawkins, the Judge bringing her toolkit to bear on the Lawrider’s gearbox and grunting in irritation as she wrestled with it. The ability to keep moving was so far a luxury they’d taken for granted, but they might not have transport for much longer if the bike gave up on them. It was showing increasing signs of strain, its suspension shot and the onboard computer displaying worrying eccentricities. Hawkins needed the communications unit fully functioning if she was going to intercept radio traffic to guide them to safety, and she couldn’t afford the A.I. to go on the fritz. (Misha, for her part, was philosophical about the slim possibility of such a sanctuary existing, but kept her opinions to herself, aware of how important it was to the Judge. Let her have something to hold on to, at the very least.) The loss of a ride would be a most troubling development indeed—it didn’t pay to linger in any one place for too long. They’d learnt that to their cost.

It wasn’t just the threat of discovery by the greys, though that was challenging enough on its own; it was seeing, like this, the devilish details of the land’s destruction. It did things to your head, watching the change being wrought upon the world, the new status quo being foisted upon it. While the global scale of it was at times simply too vast to comprehend—and she had to assume that what was happening here was being repeated in other countries: the climatic shock was too great not to be affecting their overseas neighbours—it was brought home when she gazed down on acres of grassy plains shrivelling away to nothing, or abandoned fields of blighted crops that had degenerated into an ugly hue and now gave off a fetid stench. With, so she’d heard, most germinating insects effectively wiped out, fertilisation was now impossible. Nothing would seed or sprout; there would just be tracts of barren, hostile ground. Having that laid out before you, you couldn’t help but want to weep, the sheer wrongness of it proving difficult to process. There’s something not right about this picture, she wanted to say. This is against the natural order of things.

But of course, that was exactly what it was: a perversion, a tilting of a fragile balance that served the interests of the new rulers’ anti-life agenda, and there was seemingly nothing that could be done to stop it. If the planet had any kind of consciousness—a Gaia spirit, Misha had once heard it called—it was being viciously choked, and these swathes of crumbling, blackened vegetation were symptoms of its death throes. Small wonder that she didn’t want to hang around for too long: to confront this was to test the limits of your endurance.

Put it behind you. Put it behind you, however futile that may be. Outrun the world’s unravelling.

She turned and crossed over to Hawkins, whose brow was furrowing as she twisted something deep in the bike’s chassis with a wrench. “How’s it looking?” Misha asked.

The Judge shook her head. Her speech was limited by the knotted mess of scar tissue that was the lower half of her face, and she could evidently only open her mouth so far without it causing her significant pain. Her diet subsisted mainly of liquidised rations that she could suck through a straw. Misha had never fully gleaned the whole story of what had happened to her, but then again, she didn’t really need to—they were all walking wounded now, some carrying more obvious injuries than others. If she was still alive, then she’d fought her battles against the common enemy and come out the other side still in one piece, more or less, which was some kind of small victory. But the legacy of those encounters was unmistakably writ large upon her flesh, and they told enough of their own tale that the actual details seemed superfluous.

Given the weeks Misha had now spent in Hawkins’ company, it meant the pair had developed a rudimentary sign language that the Judge clearly found less exhausting than trying to formulate words. The younger woman was surprised at how adept she quickly became at picking up what Hawkins was communicating simply from raised eyebrows and a few hand gestures. They seemed to understand each other intuitively, often predicting the other’s actions, or knowing what needed to be done without any kind of signal. They had a solid system, and it had stood them in good stead so far—but Misha couldn’t escape the fact that she didn’t know how far the Judge trusted her. Hawkins had encountered the girl when the balance of her mind was disturbed, and effectively saved her from herself. The rest of Misha’s fellow survivors had eerily vanished in uncertain circumstances, their fates unknown, and the teen had been discovered raving, on the verge of losing her sanity entirely. Hawkins had sat with her and brought her down gently.

Misha—for whom that entire episode remained something of a blank spot in her memory—was still unclear on why the Judge persevered with her, committed herself to pulling the girl back from the brink and bringing her with her. Hawkins could be forgiven for simply looking out for herself as the world crumbled; plenty of others had done just that. Yet here the two of them were—partners, of a kind. It could be that the Judge simply appreciated her company, that ironically her own mental health was in a better state having another human being to interact with, even one as borderline crazy as Misha (potentially; she’d never had another episode since) was. Maybe Hawkins simply saw something of herself in the younger woman that she wanted to protect. The teen was well aware she’d lucked out tagging along with the law officer, as she’d never have made it on her own, and felt beholden to prove herself useful should the prospect of her getting ditched ever finally come up. She went overboard in demonstrating her reliability and capability, hoping that every chore performed without complaint, or extra watch duty taken, reinforced her place in Hawkins’ confidence. It seemed to do the trick, but, nevertheless, paranoid niggles remained that the Judge was just waiting for her to make one wrong move… and Misha had good reason not to fully trust herself.

Hawkins slung the wrench back in the toolbox and motioned towards the bike with angry resignation. She stood, stretching weary limbs, and looked out across the landscape, markedly avoiding eye contact. She shook her head again, then started to pack the gear into a rear pannier compartment.

“How long have we got?” Misha asked.

The Judge shrugged, and held up a finger.

“A day?”

She gestured with her hand: <thereabouts>.

“Fuck,” Misha breathed. Hawkins nodded her agreement. “So we need a new set of wheels sharpish.”

The Judge leaned back against the Lawrider’s handlebars and picked up the comms transmitter, signalling that she was listening to it. “Stay in contact,” she intoned, the words forced out, raw and raspy.

Hawkins’ obsession with finding other uniforms hadn’t dimmed, despite the radio giving out nothing but static for weeks. “You mean we somehow lay our hands on another Justice Department vehicle?”

The older woman spread out her gauntleted palms: <no choice>.

“Which would mean diverting towards the capital.” They’d deliberately skirted pockets of civilisation as much as possible, which were dense with grey teams, and kept to the country roads. They’d found less trouble that way, but it also meant supplies were sparser. Picking up a car or truck that still had fuel was one thing; stealing a Judge’s bike was a whole other level of complication. But Misha knew that Hawkins wouldn’t be dissuaded on this one—she had to know that the resistance was out there, and that she could rendezvous with it.

The Judge threw her arms wide, indicating the barren expanse. “Want to walk?” she growled, though Misha imagined she heard the faint outline of a smile behind it.

The teen shook her head and kicked the dust at her feet. “Fuck,” she repeated.

Things got worse the closer you got to the capital, as if that was possible: the smell, the sights, the pervading sense of despair. The horror had seemingly rippled out from the Hall of Injustice at the epicentre like an earthquake. So many had tried to escape being caught in the shockwaves but the sheer weight of numbers and the ruthlessness of the new Chief’s forces meant that few within the city’s boundaries had survived the initial purge. Misha had been one of the lucky ones, bundled to safety thanks to the random kindness of a complete stranger, but plenty of others had been left behind, gunned down in their hundreds.

Some of them were still here, decaying bodies propped behind the wheels of their cars, massacred in the ensuing chaotic gridlock, but there was evidence that there had been a systematic clearance of corpses since that night. Smouldering pyres of bones lined the roads, and in the distance dotted points of flame suggested there were several burning away. It turned Misha’s stomach, and she wished they could go back, abandon this plan. Even though they were still some distance from the capital proper, you could feel the dread sense of emptiness, the void it had become, gnawing at your mind. She had argued further with Hawkins against this folly, believing it to be an unnecessary risk, but the more she protested, the more the Judge dug her heels in. She would motion to the bike, indicate the unhealthy noise that the engine was making, and remind her that it wouldn’t be long before their ride gave up the ghost entirely. The fact was the Lawrider was truly screwed—Hawkins hadn’t been wrong about the extent of its problems. It had got them over rough terrain in the past few weeks, but it was showing the strain now, kicking out oily black smoke as power outages kept rebooting the onboard computer. It would only be a matter of time before they were locked out of the weapons systems and/or something ignited close to the fuel tank. It said something of Misha’s fear of the city that she was aware that they were astride a failing machine and still she’d rather take her chances with that than go near the capital.

Of course, the teenager had reasons of her own not to get too close to the HoJ beside the obvious possibility of capture or, more likely, execution, but she had to be careful not to arouse Hawkins’ suspicions. She’d want to know why the girl had such a hard-on for staying well out of its area, and if Misha came clean that would almost certainly be a prelude to a parting of the ways. At the same time, she was aware she was compromising both of their safeties. She just hoped they could circle the outskirts and quickly find what they needed without entering the city any more than they had to, and she’d made Hawkins promise as such, citing her own personal trauma as an excuse. The Judge didn’t need to know what Misha could bring down on them if they dallied too long in the Grand Hall’s shadow.

It had been like an itch at the back of her brain up until now, a pressure she found she could push back against. She’d evidently been previously well outside the Sisters’ reach: they’d been a background presence, an electrical charge in the air you could feel in the hairs on your arms, but nothing materialised beyond that. They were looking for her, casting out their psychic hooks in the hope that they’d get a fix on her location, try to worm inside her mind and plant their seeds of corruption, but she’d blocked them. It had been relatively easy when the psignal was that weak, and they were clearly casting a wide net, but now she was getting nearer to their centre of operations it was only going to get harder to keep them out. All it took was one lapse in concentration, a drop in her defences, and they’d be inside her head, rifling through her thoughts, grabbing what they needed to direct their undead goons to pick her up—or worse, take control of her and force her to do their bidding.

They wanted her alive, she felt sure of that; or at least some approximation of it. It probably wouldn’t matter to them if she was delivered in pieces as long as her grey matter was still functioning. The thing about psychic broadcasts was that it worked both ways—while they actively sought her out, Misha at the same time could pick up the reasons behind it, their motives. Their intentions permeated their emanations, an unmistakable flavour running through them, and the Sisters’ curiosity about the girl showed strongly through their probes. They knew about Rachel, her sibling that had allied herself with the new CJ’s creatures, and the neuro-flipping that had been occurring between the pair; this kind of link was ripe for exploitation, and Misha’s potential abilities were too powerful to go to waste. She was sure that if the Sisters got their hands on her, they’d peel her brain apart for their own arcane amusement.

Needless to say, she’d told Hawkins none of this. It was a betrayal, after a fashion, that she was keenly ashamed of; she was endangering the Judge’s life through her own cowardly secretiveness and self-interest. But she reasoned they’d come too far now to imperil their partnership, and she deliberately chose to disclose nothing about the entities snapping at her heels.

Misha coughed as the wind swept smoke from the pyres in their direction, the smell sticking in the back of her throat. She tapped Hawkins on the shoulder, and signalled that this was close enough.

To go any further was to enter Hades itself. They were on one of the main arterial freeways that serviced the capital—once a never-ending flow of traffic, now a graveyard—and looking ahead, the road had seemingly been paved in bones. Layer upon layer of skeletal remains coated the ground, piling up in drifts; virtually impassable on two wheels. Hawkins slowed the Lawrider to a crawl, and weaved the vehicle between two burned-out cars to shield them from view when she saw greys patrolling the city’s boundaries. Leaving the engine idling, the Judge turned in her seat and motioned to the vibrations coming from within the engine.

<Getting worse,> she signed. <Hasn’t got much life left in it.>

Misha shrugged theatrically and looked around with arched eyebrows, indicating that they weren’t exactly spoiled for choice. They’d seen no abandoned Lawriders on their journey here, seemingly suggesting either that those resisting De’Ath had succeeded in fleeing the area, or they’d been incinerated on the spot. Hawkins raised a finger: <wait>. She flipped some switches on the bike’s control panel, and it emitted a low, regular beep.

Transponder, the Judge mouthed. Will flag any other Lawriders in the vicinity using the same signal.

“Won’t that also alert anyone that’s listening that we’re here?” the younger woman whispered.

Hawkins nodded. <Risk we have to take,> she signed. <Keep it broadcasting very briefly.>

Misha looked around nervously. An H-wagon flying overhead at that moment would pick them up instantly on its radar, and their movements tracked. She didn’t like advertising their presence so blatantly, used to travelling well off the grid. She closed her eyes and counted down the seconds before her companion deactivated the transponder—

The tone changed suddenly and Hawkins grabbed the girl’s arm, shaking her to pay attention. <Pingback,> the Judge revealed. <Found one. There’s a stationary bike less than a couple of miles from here.> The Lawrider chimed again, and then emitted a succession of urgent, clipped bleeps.

“What’s that?” Misha asked.

<Emergency protocol tagged to the signal,> Hawkins signed, frowning, squinting at the bike’s readout. <SOS. Help me.>