Talking Thistlebone – ‘Disquieting, atmospheric & beguiling, punctuated with stabs of genuine horror’

5th March 2021

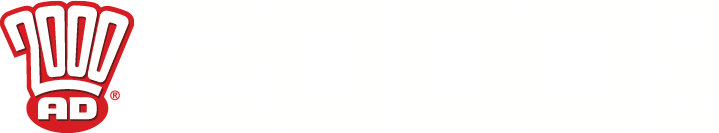

Back in June 2019, Thistlebone blew into the pages of 2000 AD like a chill North wind, bringing a creepy and deliciously dark folk horror tale to life thanks to writer TC Eglington and artist Simon Davis.

That first series is being released as a collection on 29 April, but before then we have the beginning of Thistlebone Book Two: Poisoned Roots in 2000 AD Prog 2221, out on 3 March.

Time to take a deep breath and step back into the horror as we chat to TC Eglington and Simon Davis about folk horror, creating something to terrify, and what it means to revisit Thistlebone…

If you go down to the woods today…)

Tom, Simon, Thistlebone returns this spring with the second series, Poisoned Roots – presumably bringing back all the horrors we experienced in the first series.

Now, just for those who perhaps haven’t caught up, or for those waiting for the collection (out on 29 April!), can you give us a quick catch-up for series one?

TC EGLINGTON: Thistlebone is a folk horror tale following the story of Avril, a woman who survived an abduction from a bizarre cult as a child. Decades later she is drawn back to the woods where she experienced her ordeal. Disturbing memories and dark forces stir as she recalls her past.

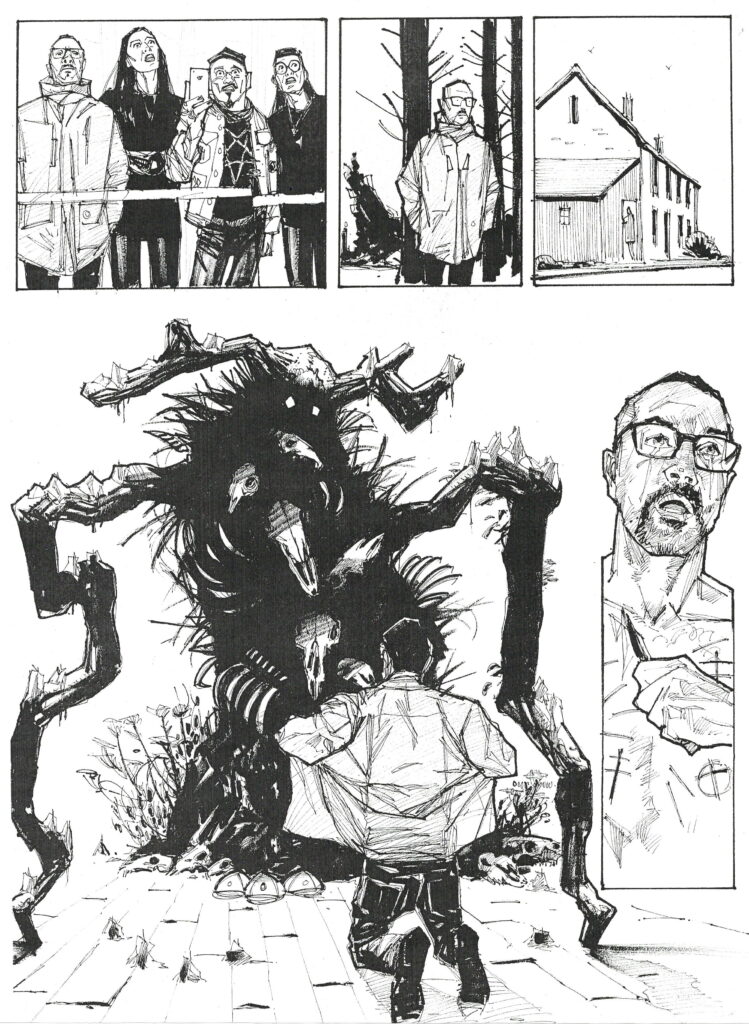

We tried to create something disquieting, atmospheric and beguiling with Thistlebone, punctuated with stabs of genuine horror. It is realistic, but there are aspects that have a dreamlike quality as the reader experiences sections of the first story through Avril’s viewpoint, memories that are distorted by her confused mental state. Simon’s artwork was been perfect for this, as his style conveys mood so well.

More deliciously dark goings-on from the woods in Thistlebone Book One)

SIMON DAVIS: Yes, everything Tom said. I have a love of the genre that’s referred to as Folk Horror…one inextricably linked to nature, isolation and the old ways. We hadn’t worked together before yet shared a love of the genre and get on well, so this seemed the perfect opportunity to create something new together.

Hopefully it was unsettling. Because of modern society’s general disconnect from the natural world…food production, species depletion etc… I feel that nature holds a lot of primal fears for the modern city dweller. I think setting the first story in the overpowering presence of a forest already creates a feeling of unease and oppressiveness. It’s a folk-horror story in a lot of ways…the fear of modern industrialisation, myth and fear.

And now, what can we expect from this new series of Thistlebone? After all, anyone that’s already seen the conclusion to the first series would imagine that the book was pretty definitively closed on Avril’s experiences with the Thistlebone cult. So how on Earth have you managed to continue the tale – do you grab a thread from the first series or does it head off in some new and horrific direction?

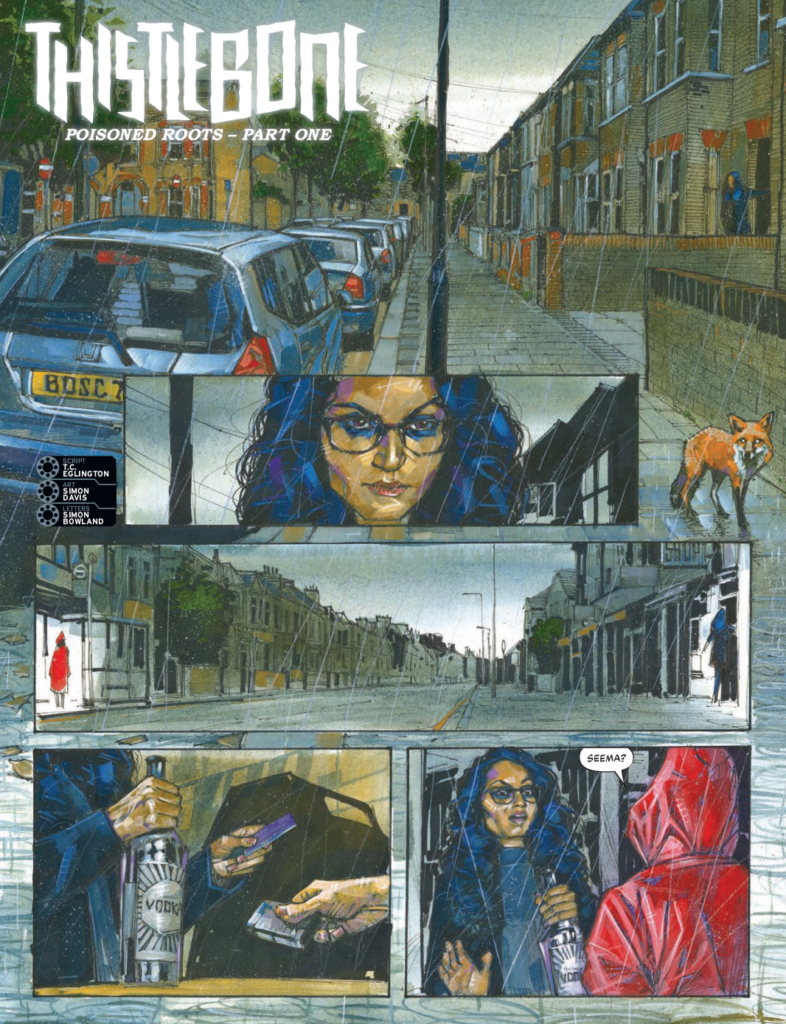

TCE: With the new series of Thistlebone, we follow Seema, the journalist responsible for persuading Avril to return to Harrowvale in the first series. When an archaeological discovery at the centre of the woods reveals ancient skeletons killed in ceremonial methods, Seema is drawn back into the mysteries surrounding the Thistlebone cult. The more she digs into the past, the more she reveals the malignant roots of the cult, ultimately putting her own life at risk.

SD: I think Tom and I had such fun on the first series, we felt a second was a good idea. It seemed to go down well and find a home with the readers. The first was a self-contained story but also within that there is scope to continue. Because the premise is bound up with history and that the land has born witness to a multitude of civilisations and will do so again is a very potent way to frame the present day. We are just a little and brief connect with a place and the awareness of that is fertile ground for storytelling.

TCE: Chronologically, it follows the events of the previous series, but there is more explanation of the past.

It is a story of the old traumas of the land haunting the present, which seemed an apt theme for a modern folk horror tale. Seema is at the centre of that. Unlike Avril, she is a rational person caught up in an obsession for truth, but encounters disturbing beliefs that challenge her own views. She confronts the differing perspectives of Hillman, Malcolm Kinniburgh, and Avril in an effort to find answers, but is only drawn deeper into the horror.

I think with this story, I wanted to create a layering of events, a sort of fictional psychogeography for Harrowvale to give it more depth. The influence of those distant terrors echo throughout the story in bizarre and disturbing ways.

Are we looking at another 10-parter here?

TCE: This series is 12 episodes, giving us a bit more room to explore the characters, landscape and nightmares of Thistlebone.

you really don’t want to be part of this trip into the woods – from Thistlebone Book One)

In the first series, we saw an exploration of the isolation of rural life, the insular nature of it all, and the inevitable reliance on, respect for, and sometimes something akin to a worship of nature and the old ways.

It was also a series that used the already damaged/fragile mental state of Avril to tell the story through a single character’s perceptions, often distorted and unreliable, something that really works wonderfully well when you settle down and read it all in one go (did we mention there’s a collection out in April?)

SD: Tom wrote that really well in the first series and the feeling of the unreliability of memory continues in the new story…but for a different character.

It is my role as the artist to add elements of this into the visuals too…incidents vary and change depending who’s telling the story which hopefully achieves a state where , as a reader, you don’t really trust any of the characters to be a reliable witness to what’s actually happened in the past or in what is happening now.

TCE: A lot of the horror of Thistelbone is rooted in beliefs and the power beliefs have over us. There is also the psychological unease of the landscape’s effect on people. And there is, of course, some outright visceral terror. It helped to have Avril as an unreliable protagonist, which allowed us to have imagery in there that hovered between the real and imagined.

Tom, one very creepy aspect of Thistlebone was the idea of the speech patterns of the cult shifting into the speech patterns of other characters, never more chilling than that moment one of the kids appears to speak in tongues.

TCE: I was fascinated with the idea of glossolalia, and how to convey audible hallucinations in comic form. It linked nicely to a piece of experimental writing I had tried years ago. I had been playing around with William Burroughs cut-up technique, but I took it a step further and cut up words into smaller and smaller chunks. I would take famous passages and use pairs of letters from each word in a sentence to compress it down. It created this sort of jumbled proto-language, an uncanny babble that feels familiar in parts but is also just distortion. It feels a bit more realistic than trying to write an approximation of glossolalia, especially since I could take famous sayings and use that as my source. I could then play around with it to give that feeling of meaning emerging from it.

With the second series I use it once again, and there are some weird coded messages I mixed in, partly for my own amusement. The original idea also has a slightly tenuous folk horror connection, too. I had been struck by a line in a book about a myth that human language had been seeded from the sounds of rivers, and that was what I was trying to create with this invented degraded language. I had notebooks with pages of this babble written in it.

I have proper hobbies now.

Despite the first series being just 10 parts, a mere 50 story pages, it’s a collection that reads a lot longer. Partly this is because Simon has constructed his pages in such a way, it seems to me, to be open and expansive, yet cleverly contain so much, allowing there to be far more going on in a short tale than would otherwise be the case.

SD: Yes , the visual side of it was always going to be something that I would try and make quite dense. 50 pages isn’t very long but to describe a story by how many pages it is is not necessarily a fair one. Hopefully we’ve packed it with ideas and visuals that will permeate far beyond the actual storyline.

TCE: With the first series, it was a very conscious decision to give Simon’s art space to breath, yet tell a compelling and nuanced story. Atmosphere is everything in folk horror, and the imagery was key to creating something unique. While some of the tropes of folk horror are there, we tried to push it in a different direction.

Where did the inspiration for Thistlebone come from? Was it something rooted in where you grew up, that sense of the rural English landscape and people?

SD: Yes. Tom and I have a love for the countryside and nature. I live in East London but only moved here at 40. Before that I lived in villages in Warwickshire and Worcestershire so have a deep love for all things rural. So, when putting together we had long chats, went for a ramble in some woods and Tom sent me synopses to hone it from there.

TCE: The inspiration for Thistlebone came from a number of sources. Originally, I had considered adapting particular British folk mythologies into a story but I wasn’t happy with any of the attempts I created along these lines. However, I did pick up some of the general ingredients of local mythologies. What you tend to find when you do a bit of digging is that a lot of rural folklore has very muddled origins, with meaning and ritual projected onto them by different generations over time. This in itself fascinated me, and it fitted neatly with more current horrors; Fear of the land and fear of belief systems.

We had discussed doing a folk horror tale for a long time as it was a genre we both loved and it seemed it hadn’t been done much in comics. There were lots of conversations about the sorts of things we both liked, and what we wanted to include. We both went on a trip to a local woodland for inspiration – ancient yew trees and fallen oaks. The story went through several versions that I showed Simon, before we settled on the final approach. I was interested in the idea of a cult with a charismatic leader, like a mix between Aleister Crowley and Charles Manson, and how far those beliefs could lead someone to doing terrible things. Visually, I tried to include lots of stuff that Simon would enjoy, the sort of wonderful British imagery used in local folk ceremonies, as well as the scenery of untamed countryside, and lots of nods to folk horror films.

There are a few direct references. The mask, for instance, is inspired by an ancient deer bone mask discovered on an archaeological dig in Yorkshire. There was something instantly striking and primaeval in its appearance that seemed to fit perfectly for this.

TCE: In the second series, I also found inspiration from an actual case of a tree collapsing and revealing human remains tangled in its roots – this has happened on a few occasions, apparently.

There are also a couple of real events that I drew inspiration from for a key part of the second series, but I can’t discuss them without ruining some of the story. Suffice to say, it is appropriately strange and nightmarish.

Simon, can you give us an idea of the process you’ve used on Thistlebone?

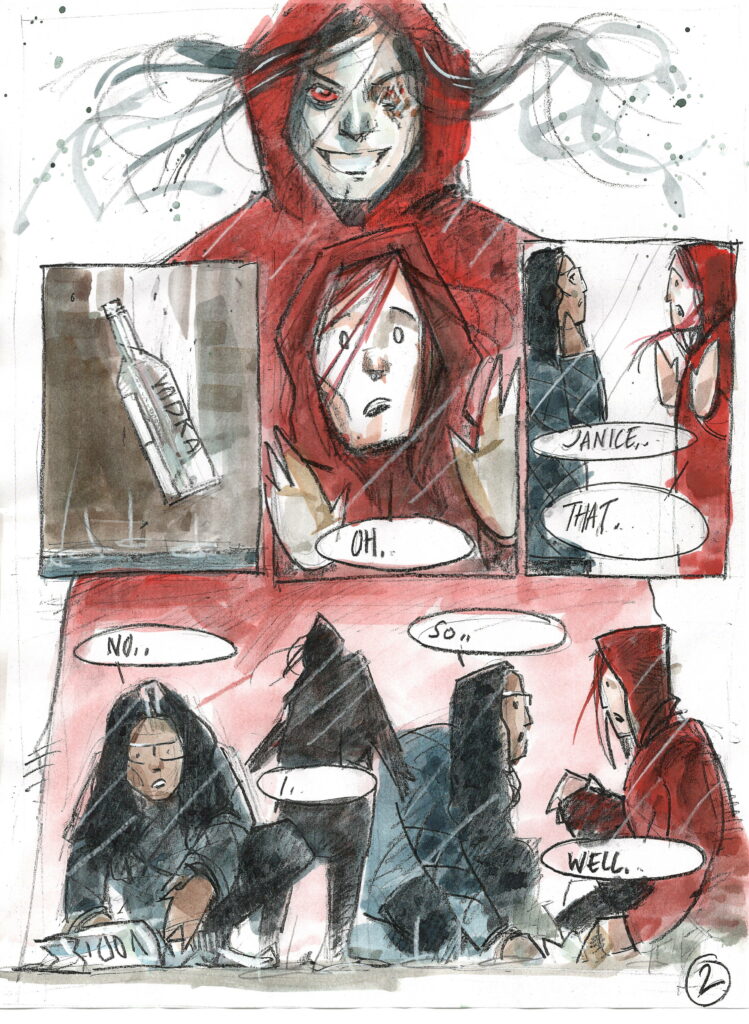

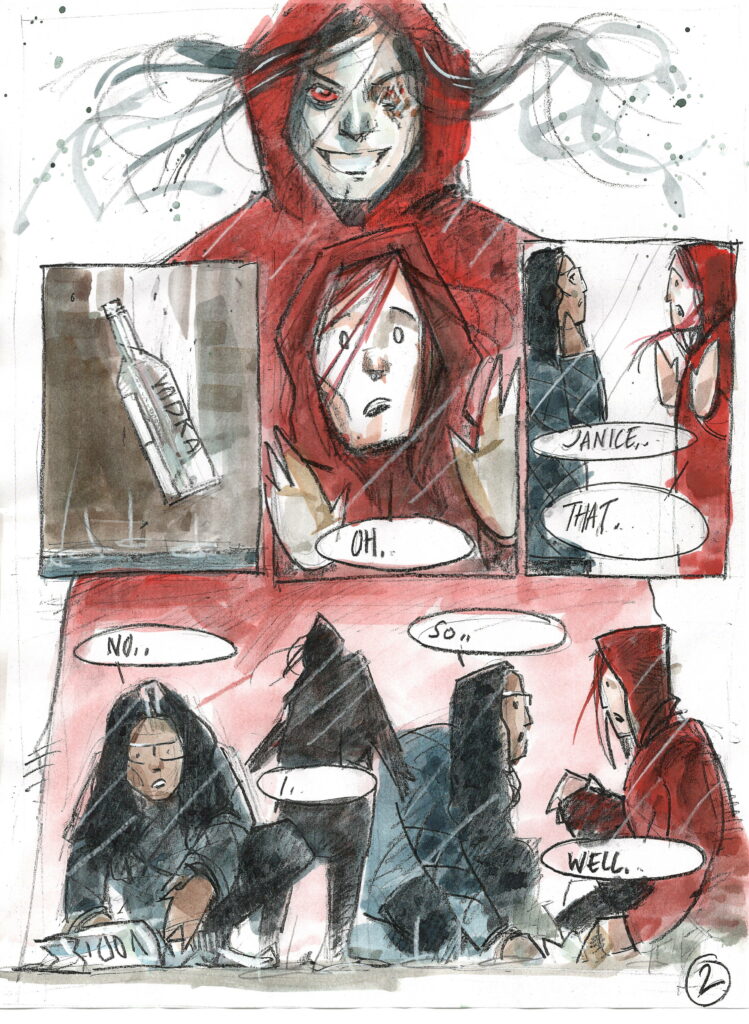

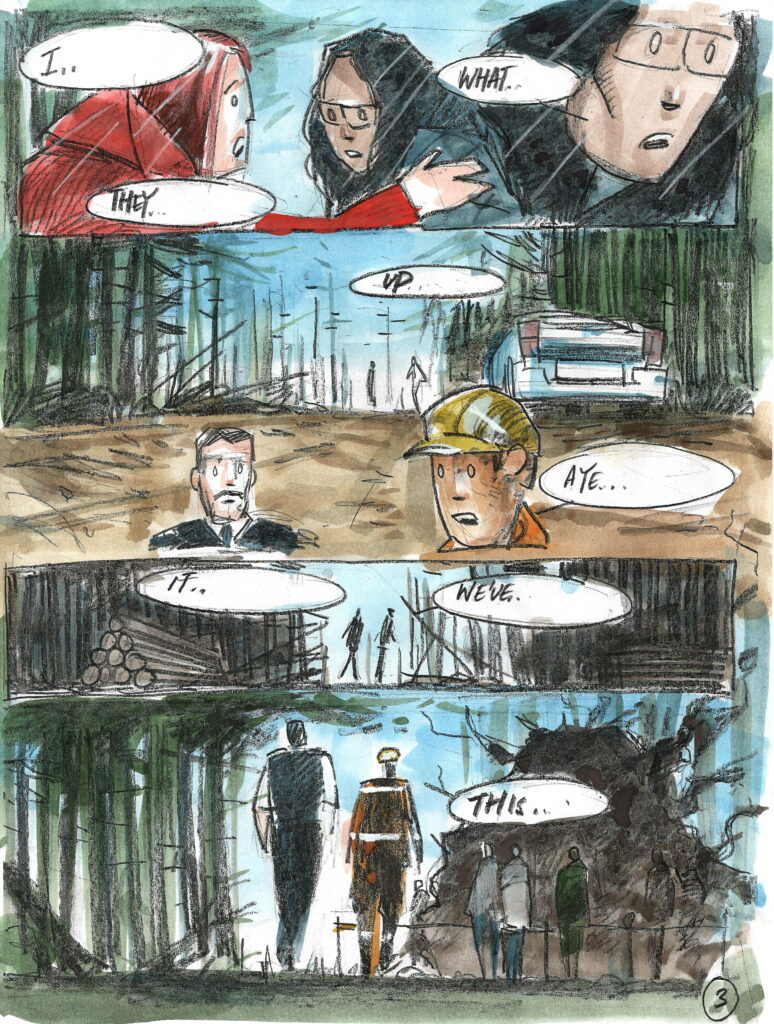

SD: My process is quite labour intensive but I find that it works ok. I don’t use computers at all… not because I fear them but just because I simply love physically painting. I start with getting together a lot of reference… I use models for the characters as this helps with consistency and then do the complete story in watercolour roughs.

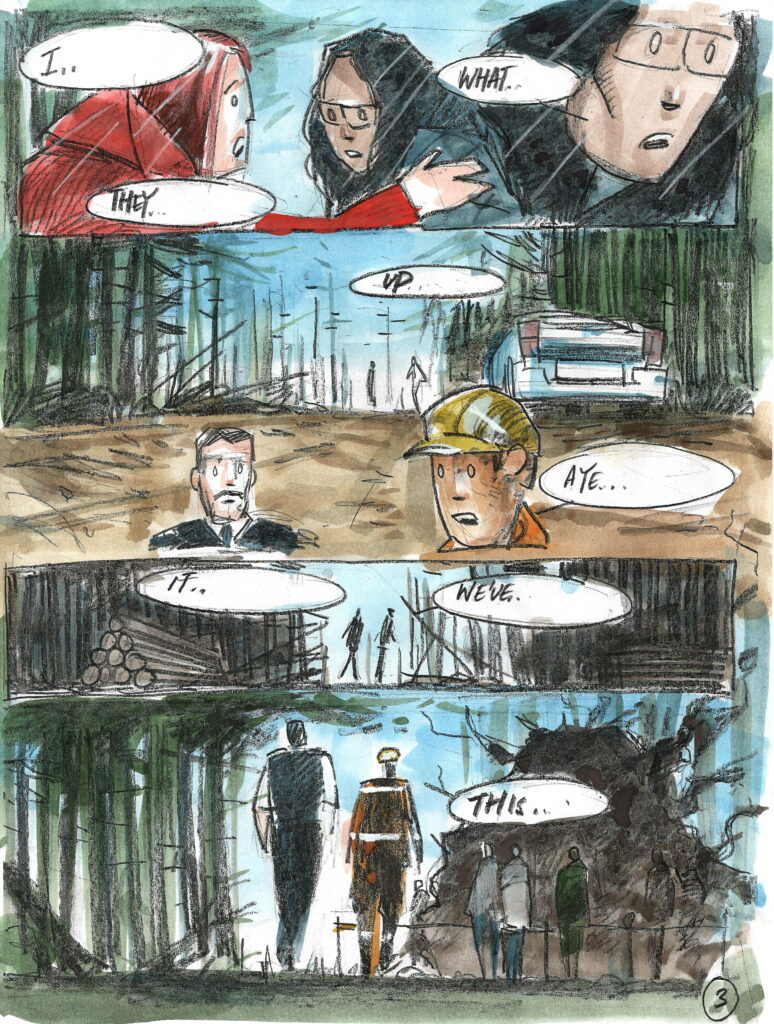

I started this extra preparation when doing Slaine and tonally it really helped. It hopefully gives the story a better flow as I am aware of what is to follow and can change mood to best fit with the narrative.

The final pages are around A3 size and are gouache, ink and crayon on hot-pressed watercolour board.

SD: This story, Poisoned Roots, was started after a gap of about a year. I took a year off comics to concentrate on straight painting. I felt I needed to do this as both strands of my creative life are important to me and ,to a large extent, when I’m doing comics I get so immersed in that world that I can’t devote any serious time to painting.

After a year or so, I wanted to come back to Thistlebone. Tom had already written the story and he and Matt Smith had been very patient in waiting for me to start. As I mentioned before, I use a lot of models for the strip but this year, with the pandemic and the various lockdowns, has proved quite challenging as regards that. I know it’s nothing in comparison to what a lot have people have had to deal with but it still posed a few logistical problems. Socially distanced and remote photos via WhatsApp were the way around it.

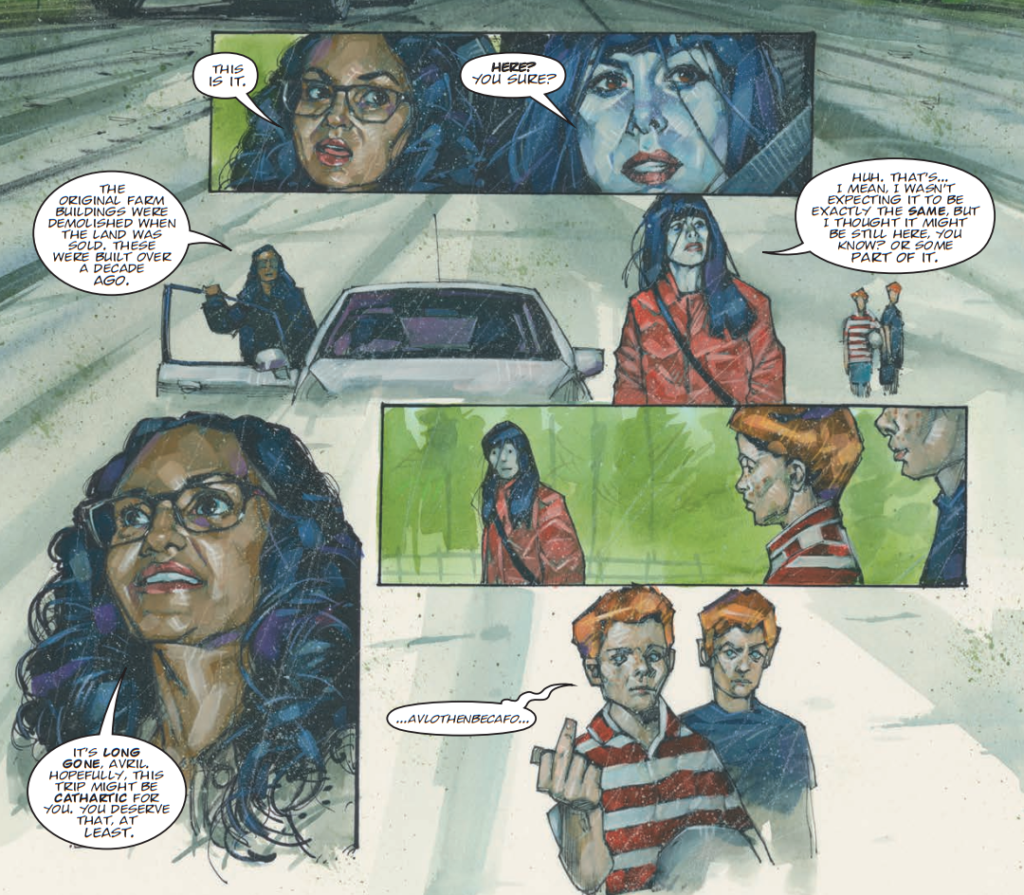

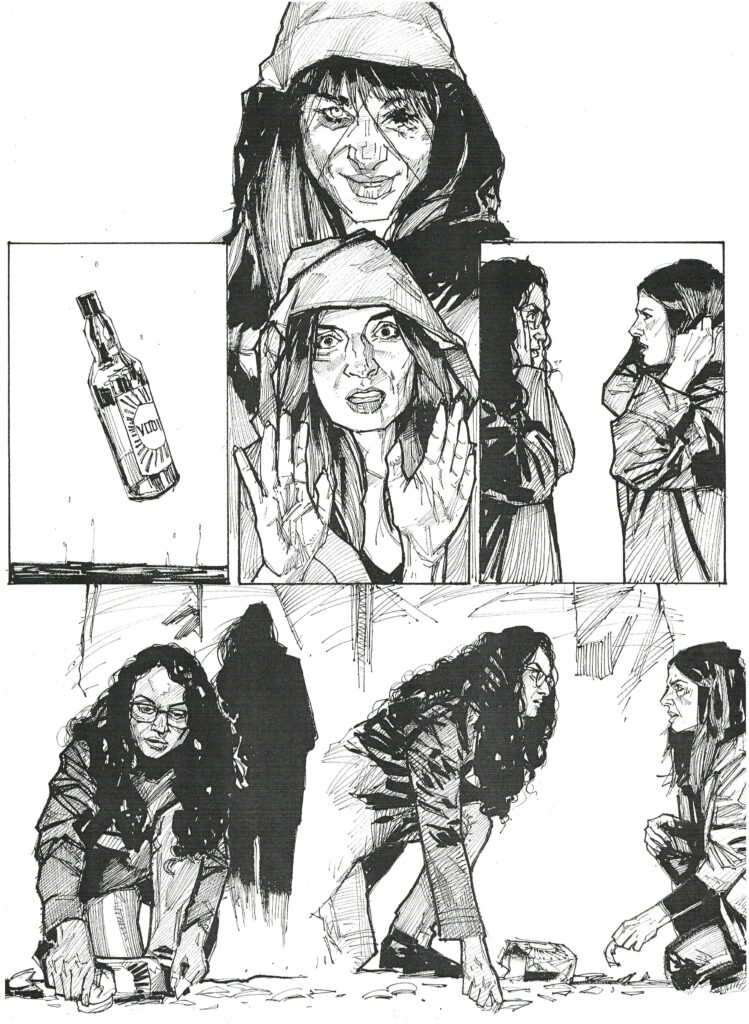

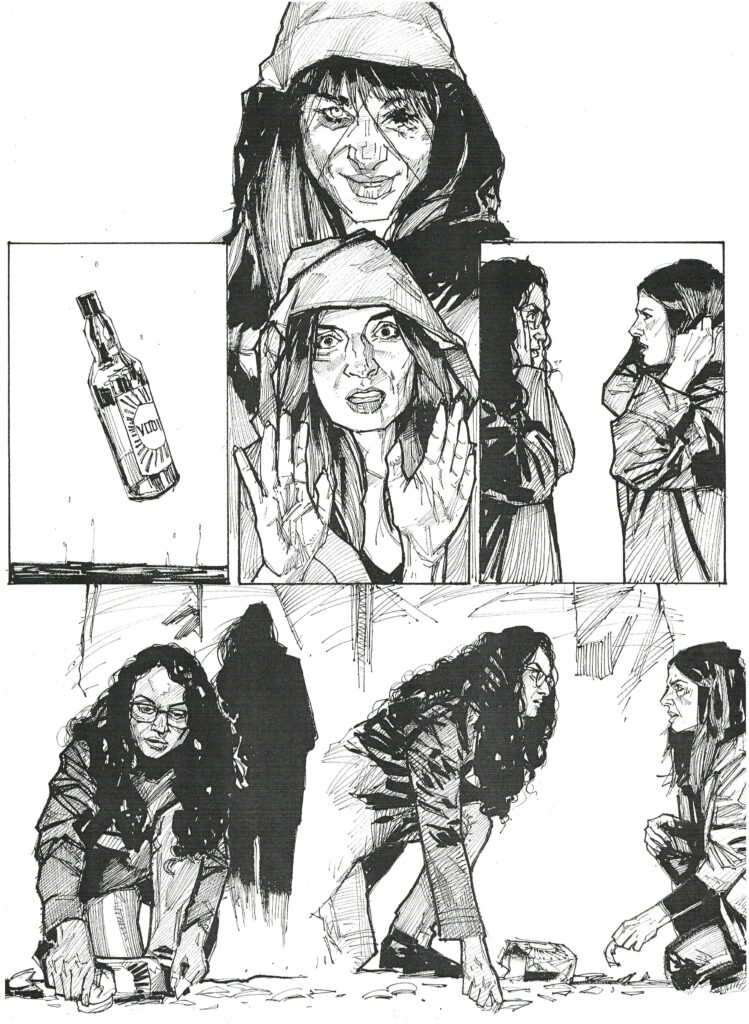

This is what Simon calls ‘rough layouts’!

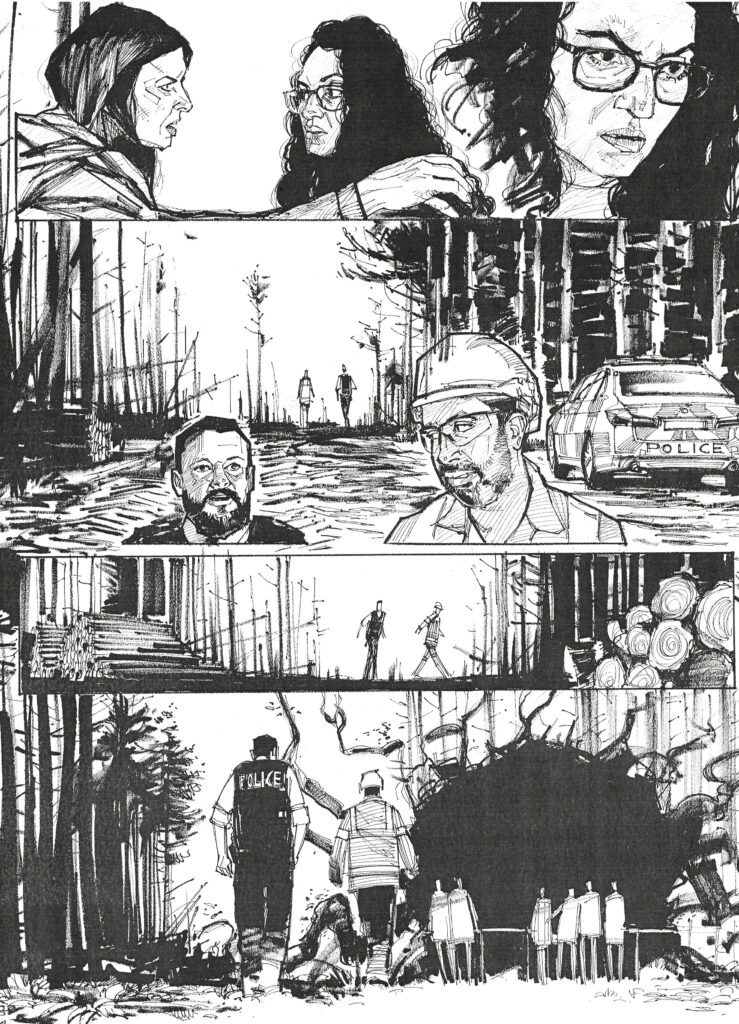

And the finished B&W!

Now, you mention the process of doing watercolour roughs with your work – we get to see some of these in the forthcoming Thistlebone Book 1 collection (above) and I can confidently speak for readers when I say that it’s amazing to see the quality and style of your watercolour roughs.

In fact, I know a lot of artists who would see these roughs and consider them print ready in many ways.

SD: Ha! Thanks…there is an energy to them which I like and often find hard to transfer to the final artwork. These roughs are a vital part of the overall storytelling. This time, due to the problems outlined above, I did the complete story in rough form before I started to save a bit of time, while we were all in isolation. This really helps me to be able to shift the storytelling visually and tonally at critical times so that it doesn’t look all the same. This is quite a problem with episodic storytelling in 2000 AD. Episodes can look great individually but when they are collected, there is no variation in tone so it all looks a bit ‘samey’.

When it comes to your art here, you’re doing so much on each and every page. But there’s a few specific things I wanted to ask about.

Firstly, something I noticed when it was first published, but seeing it in full in the collection really brings it home to me – it feels as though there’s so much of the art through the first series is predominantly based on a horizontal full page width panels…

SD: Ah yes, I do tend to approach my layouts quite cinematically so this horizontal panel width is a useful solution.

Similarly, there’s very few pages with anything like a nice, neat grid going on and a lack of solid, rigidly defined panel borders, adding to that organic feel of a page, allowing the flow of the background to continue.

SD: I also try (and Tom is great for giving me the space) to do an overall image and then place the panels on top of it. This kind of gets around having to do a background for each panel, to show where the characters are.

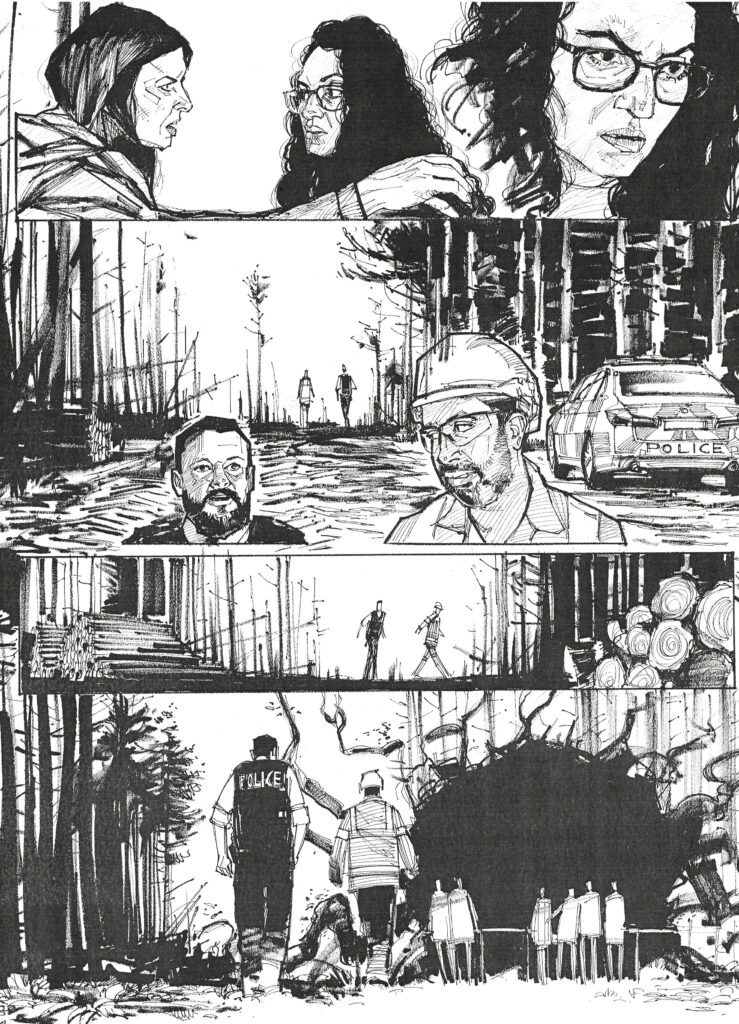

More of those ‘roughs’ – not too rough at all!

And the same page with finished B&W.

Simon, your career in comics has been dominated by your fully-painted style, on strips such as Sinister Dexter, Black Siddha, Stone Island, Missionary Man, Judge Dredd, Ampney Crucis, and Slaine for 2000 AD. But, unlike a lot of your contemporaries, you haven’t (as yet) been lured across the pond, with, as far as I know, just a single JLA graphic novel, Riddle of the Beasts, for DC Comics. Is this a deliberate decision on your part? Is it a case of fitting in very well at 2000 AD?

SD: I love 2000 AD and can’t see any reason to go elsewhere. To be able to do fully painted artwork on a weekly comic is almost unique I imagine. I cherish the simplicity of my working life for 2000 AD too…get script, do painting, deliver pages, have a beer with the editor… it’s something that I can’t imagine happening elsewhere. I have no interest in superheroes so that’s why I haven’t painted them. However, US comics in the late ‘80s and early 90’s were incredible. A lot of painted artwork and diverse and crazed ideas but that seems to not be the case now. To be honest, I don’t read comics regularly anymore…apart from Hellboy that is. Some of the current artwork on the US titles is incredibly beautiful though and I love love LOVE looking at it…Jock, Ben Oliver , Otto Schmidt etc but I have zero desire to do that stuff myself.

However, your work in comics is just part of what you do artistically. You’ve worked on storyboards for TV and videos for Muse and Tori Amos – what was that like, did you get to live a little of the rock and roll lifestyle?

SD: That was a while ago and they were just fun things to do really. I like music so it seemed a natural thing to do. I like not being defined as just doing one thing. I designed Oscar Isaac’s tattoo in Annihilation and painted the poster for Ben Wheatley’s last film and these jobs were a joy to do. Working with people I really admire is a real bonus.

You’re also a well-established and award-winning painter, with full memberships of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists and the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. Where did your love of portraiture come from?

SD: My father was a painter so I have always had art around me and portraiture always fascinated me. Comics are beautifully throwaway but usually the character is king over the artwork side of things. Painting, for want of a better word, proper paintings was something I natural moved into as there is a little more gravity and longevity to it all. I’m currently vice-President of the Royal Portrait Society (RP) and really like having these two strands to my creative output. Boo Cook and I have a folk-horror style music project called Forktail too (that Tom contributes to also) so that completes my unholy trinity of creativity.

Was it something that was always there and informed your comic style, or did comics come first?

SD: I have worked for 2000 AD for 27 years this coming September…I know…terrifying! So that came first. The two differing disciplines do often cross-pollinate…usually composition-wise more than anything.

Finally, what can we expect from you after this series of Thistlebone? Are you already planning series three? And what other delights on the comic page (or anywhere else!) can we look forward to?

TCE: As for future projects, I have several exciting things on the go at the moment but nothing I can talk about just yet. I would love to do more Thistlebone as it has been so rewarding to work on. I’m just waiting to see how everything settles into place after the upheaval of the last year.

SD: We haven’t really talked about it. I have a lot of painting commissions and projects that have been piling up that I must turn my attention to but never say never.

And with that, we leave Tom and Simon busy plotting how best to fill our dreams with Folk Horror imagery and nightmarish creations.

Thistlebone Book One is out on 29 April. Thistlebone: Poisoned Roots starts in 2000 AD Prog 2221 – out 3 March from wherever great comics are sold, including the 2000 AD web shop.

And finally, it wouldn’t be fair to just show you Simon’s beautiful process pages in those small versions, so here they are in all their glorious and gorgeously disturbing glory, complete with a potentially small spoiler with the final page of Part One of Thistlebone: Poisoned Roots… (So only read on if you’ve already seen Poisoned Roots part 1 in Prog 2221…)

Roughs (Hah!) – Page 2, Part 1 of Poisoned Roots

Finished B&W – Page 2, Part 1 of Poisoned Roots

The roughs (seriously, roughs???) – Page 3, Part 1 of Poisoned Roots

Finished B&W – Page 3, Part 1 of Poisoned Roots

Oh C’mon Simon? Roughs, really??? – Page 6, Part 1 of Poisoned Roots

Finished B&W – Page 6, Part 1 of Poisoned Roots