“The Mediator Between Face and Fist Must be the Heart!”: police and justice in ‘Megatropolis’ and Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’

12th October 2021

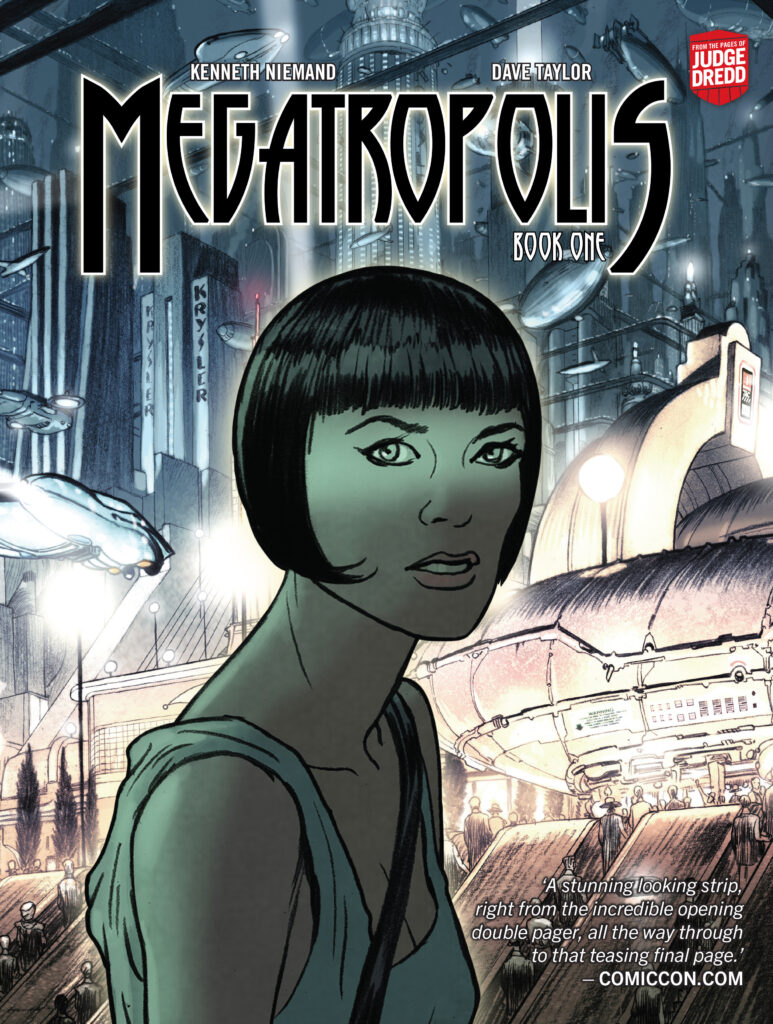

The collection of Kenneth Niemand and Dave Taylor’s stunning Elseworld-style art deco noir Megatropolis is out this week!

Continuing our series of short essays commissioned from selected comics critics that explore 2000 AD and the Treasury of British Comics’ latest graphic novel collections, Harry Kassen explores the deeper connections between the series, which plays on the world and themes of Judge Dredd, and Fritz Lang’s classic 1927 movie Metropolis.

Warning: this article contains spoilers for Megatropolis

Through the years, many of my favorite comics were the ones where creators got to just throw continuity to the wind and have a ball, the wilder the better. This is why I was so pleased to see Megatropolis by Kenneth Niemand, Dave Taylor, and Jim Campbell.

Functioning as a sort of Elseworlds for the Judge Dredd universe, it translates all the things you know and love from Mega-City One into the world of Megatropolis, a sort of Jazz-Age-cum-techno-dystopia that can only be described as the unholy lovechild of The Great Gatsby and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, an inspiration that Niemand and Taylor tout in the title itself.

The influence of Metropolis is undeniable, shaping the city into a chasm interrupted by towering blocks of glass and concrete, with a sky full of airships, criss-crossed by floating highways, all lit up by the twinkle of a million incandescent lamps. Despite this, the story of Megatropolis owes just as much to the context of Fritz Lang’s 1927 film as it does to the content. The city of Megatropolis exists as a physically and socially stratified world, with the rich floating high above in their towers and hovercraft, separated completely from the poor who live below. The cast of characters as well, will be familiar to anyone with a knowledge of the classic Jazz Age and Depression noir tales, with crusading reporters, high society psychics, and corrupt police chiefs. None of this is a particular surprise though. From the title to the marketing to the backmatter design notes, Metropolis is hailed as an influence on the book. Any overlap of aesthetics or premise is virtually promised to any reader at the door. What struck me about Megatropolis is the deeper level on which it integrates the philosophy and themes of Metropolis.

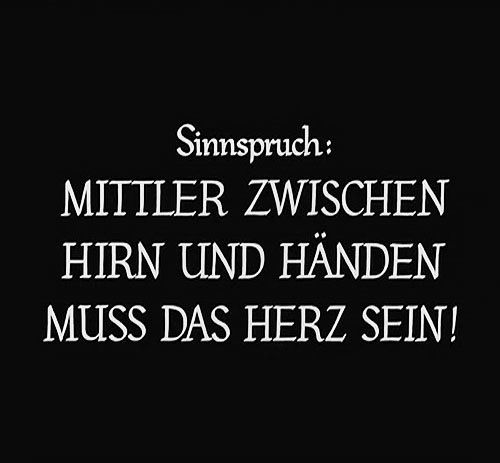

Metropolis is a movie that wears its themes on its sleeves. It opens with an epigraph, pictured above, stating its moral, a line that is often repeated throughout the movie, and serves as the film’s closing line. The basic conflict of the film is that Freder Fredersen, son of the leader of Metropolis, sees the squalid conditions of the working class, and seeks to change them, but at the same time the working class rise up and wreak havoc, as a mass of angry people with no direction. It’s more complicated than this, obviously, but the solution comes about when Freder steps in to mediate between the workers and his father, the master of Metropolis, since they clearly cannot live without each other, but also cannot come to terms unassisted. This is a message and political philosophy that is at best harnessed by liberals to support incrementalist attitudes and policies of reform, and at worst channeled by fascists as evidence that society dissolves without their ironclad hold on culture and labor, and rigid insistence on traditional and ritual practices.

Similarly, from what I understand, Judge Dredd as a franchise does little to conceal its messages. Dredd stories, and Niemand’s Dredd stories in particular, do little to conceal the strip’s core message – that policing is a problematic institution and needs to be dismantled. Due to the overwhelming number of Dredd strips, I’ll let this point stand on its own.

What interests me in all of this is where Megatropolis is on this axis. It follows a traditional noir plot, focusing on Detectives Joe Rico (our Dredd stand-in) and Amy Jara as they investigate the rampant corruption in the city government and police force, as a mysterious vigilante murders their suspects. While this is very different from the story of Metropolis, it aligns itself time and time again with the idea of a mediator or a middle way. The very fact that the book focuses on the police as its heroes, with both the corrupt city leaders and the vigilante targeting them framed as being in the wrong, demonstrates where its values lie. Even the labor leader John Clay, the only non-criminal member of the lower classes with any significant narrative presence, is shown to be hostile to the police, and somewhat suspect as a result.

The clearest manifestation of Megatropolis’themes is at the climax of this volume. Rico and Jara are at a high society party where they believe the vigilante robot known as “Judge Dredd” will attempt to assassinate the corrupt mayor. When Dredd makes his appearance, he grabs the mayor and moves to throw him to his death, but is stopped by Rico, who engages it in a debate over the law. Dredd’s position, that it’s been programmed to believe, is that any law that protects criminals is corrupt. Rico’s stance is that the law has to be pure, even if the people who uphold it and benefit from it are corrupt. This line of reasoning short circuits Dredd, who then submits to execution by other cops on the scene. In scenes following this confrontation, we see that Rico is now the head of a task force tasked with cleaning up Megatropolis, and that Dredd’s creator is using Rico as a model for what Dredd was missing: a conscience.

This is clearly a different position than the usual stance Dredd comics take on policing, and while it doesn’t map neatly onto Metropolis’ conflicts, its ultimate resolution is very similar, to say the least. As I said before, comparing this comic to Fritz Lang’s movie is the obvious move, but the degree to which Niemand and Taylor have recast the source material in the mold of their inspiration is fascinating, and a sharp way of manipulating the material to drive at certain questions. Will the series continue to espouse the reformist-at-best philosophy of Metropolis or will it attempt to interrogate those ideas in future volumes? I couldn’t tell you now, but wherever it goes, I’m excited to see what it does.

Harry Kassen is a writer and comics critic, currently working as the Features Editor at Comics Bookcase, where he created the recurring ‘Comics Anatomy’ feature. You can find him on Twitter at @leekassen, where he shares his thoughts on comics, food, and everything else.

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.