INTERVIEW: Rob Williams and Henry Flint on Judge Dredd: The Small House

28th September 2018

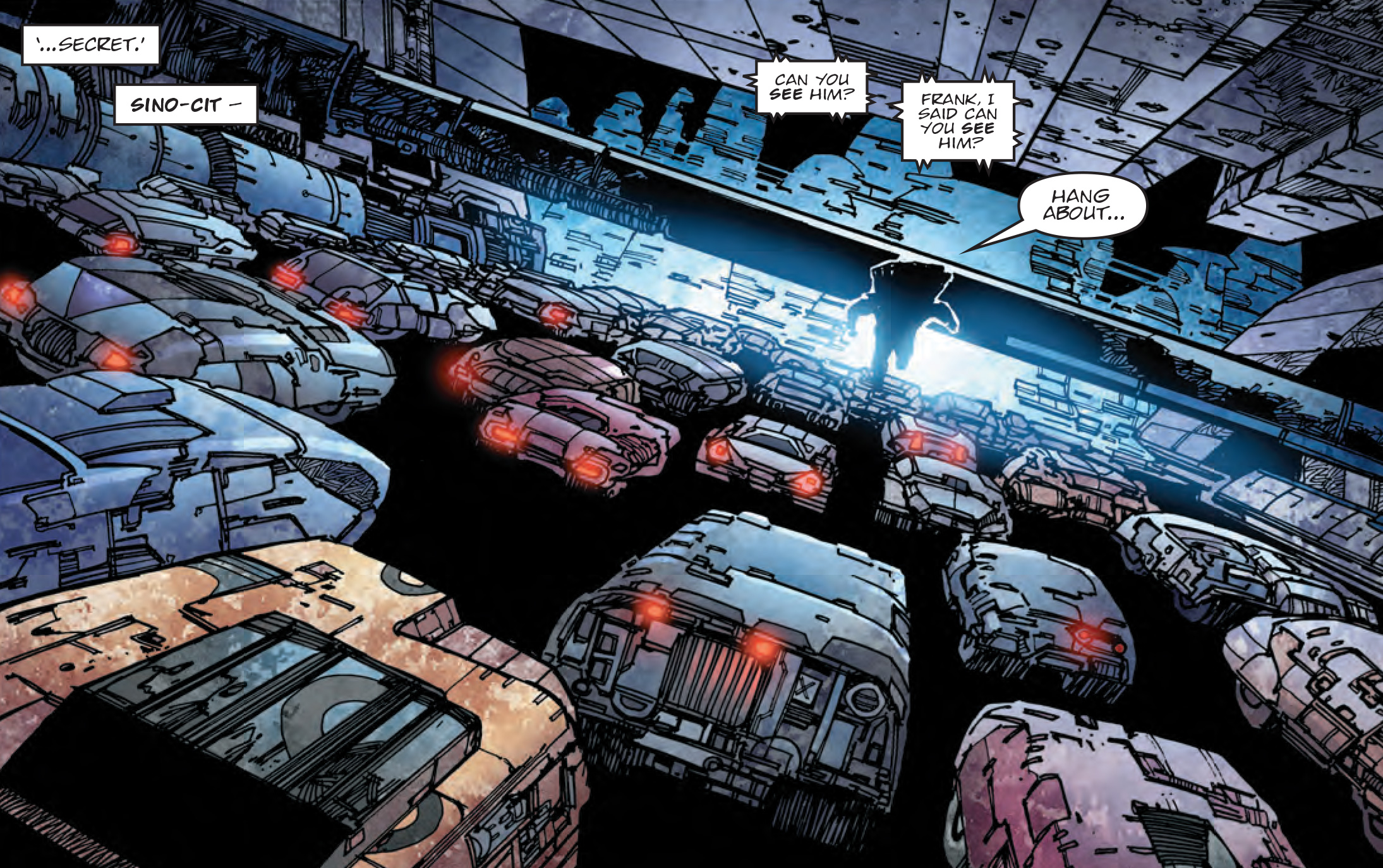

The landmark 2000 AD Prog 2100 is out now and features a new 10-part Judge Dredd epic, ‘The Small House’, with Rob Williams and Henry Flint returning to long-form Dredds for the first time since they wrapped up their incredible Titan saga.

“There is a very big moment in Dredd’s world coming. We’re dealing with it here. But I can’t say any more than that” – That’s just one of the things writer Rob Williams had to say about events in ‘The Small House’ in an interview you can find in Prog 2100.

It’s a series that promises to tie up many of the threads from Williams’ Dredd work that have been in play from Trifecta, Titan, and Enceladus. It could well be the biggest thing to happen to Dredd, The Justice Department, and Mega-City One since Day of Chaos, following up on the mysterious secret team that Dredd’s been running in the background for the last couple of years.

In the pages of Prog 2100, Richard Bruton chatted with both Rob and Henry about what we can expect from ‘The Small House’, but there was so much more than would fit in the pages of the Prog. So here we offer something of a ‘DVD extras’ section, with all the fascinating stuff that didn’t make it into Prog 2100, where we talk all things Dredd with Williams and Flint…

What do you think it is that keeps Judge Dredd so fresh through the years and leads to each new generation picking up the strip?

Rob Williams: It’s probably the different voices and visuals and the weekly nature of the strip. Necessity means that new stories keep rolling through, largely by different people using the template set by Wagner, Grant, Mills and co. And it’s sci-fi that allows you to reflect the our current world. The news is always a fresh source of material for Dredd.

[With ‘The Small House’] I wanted to do a Dredd that confronts the nature of the Judges. The fact that we’re telling stories about what is basically an authoritarian regime. if you’re going to portray these characters as heroes – and the Judges are, sort of – I think you have to be honest about, well, fascism too. It’s a fine line. There’s a lot of real-world politics that I felt, needed a bit of refection in Dredd’s world. Fascism’s on the rise. We probably have a responsibility if we’re being creators of Dredd to show that there’s a cost.

‘The Small House’ features the return of a certain tea drinking Judge, but you’ve also got the separate storyline with another character that’s become hugely popular, the magnificently bad SJS Judge Pin, in your Dredd stories with Chris Weston, the Bolland to Flint’s McMahon, as they were recently described. What’s happening with Judge Pin?

RW: Chris and I have future plans for Pin. We know the end of that story. We just need to get Dredd there. She’s a really intriguing character. An SJS serial killer who’s been working unknown for years. So many Judges die on the streets, she can cover her bodycount and no one is aware.

Rob, the Titan saga (Titan & Enceladus) was your first big solo outing on Judge Dredd, although, of course, you’d both already been heavily involved in MC-1 (and with Henry) with Low Life.

RW: Yeah, I think it’s something you have to build to. Dredd’s initially very daunting to write. You feel the weight of all those great stories you grew up reading, and also it is so very easy to see him, and write him, as a robot – which leads to very limited stores. After writing him for a while I kind of felt like I was ready to write a story about the man. Which is why it was called ‘Titan’ – that’s referring to Joe, and that’s what Aimee Nixon wanted to rip down. To destroy his legend and prove to him that he was just a killer using the badge and uniform as an excuse. I’m not entirely certain Aimee wasn’t right about that.

Also, Titan was originally going to be a Low Life story about Aimee dealing with life up in the prison. But I thought it was a lot more interesting if it was a Dredd and Aimee turned out to be the bad guy. Which was her journey all along.

You’ve both been involved in the creation of various 2000 AD characters over the years, including Dirty Frank and Aimee Nixon, who both played a major role in Titan. How does that creative process work?

RW: Low Life came about because, if I remember right, Matt Smith asked if I’d like to do an undercover Judge Wally Squad strip. I wanted to make the lead character a hard-edged female – someone who’s ‘super’ power was that she was a great liar. Henry drew her with this broken nose, which was perfect. Dirty Frank showed up on a whim as a background character. Henry drew him to resemble Alan Moore. But Frank just had energy on the page from day one. He sort of demanded more room in the story. That was totally unplanned.

Titan and Enceladus was also the final arc in the Aimee Nixon chronicles you began back in Low Life. How long ago did you envisage this ending for the character?

RW: I’d never intended Aimee to end up dying up on the Enceladus moon or part becoming an alien ice spider creature. Weird where stories go. Aimee was always The Big Man – the Low Life’s mystery big bad. I always had her journey to be she eventually realises that she’s far more a criminal than she is a hero. So her going to Titan made sense. Enceladus came about because I had the image in my head of her coming back to Mega City One for revenge on Dredd and the Council, and I needed to work out a way of doing that. The best characters usually tell you where the story needs to go.

Henry’s art on Titan really was just superb, with a Hershey who just bristled with pissed off authority in practically every scene. And then there’s the fabulous colouring throughout, including those really striking pages shot through with red emergency lighting. And that image on Dredd on horseback – a nod to Miller’s Dark Knight?

RW: I think Henry said to me at one point that he fancied drawing Dredd on horseback. I’d written a sort of “phantom” horse into my Dredd story ‘The Man Comes Around’ that RM Guera drew so beautifully. So bringing the horse back at the end of Enceladus – like a symbol of Dredd at the very end – that felt really exciting. Taking Dredd to some primal, guttural place. The subjective walls of reality kind of crumbling a bit.

Henry Flint: I prefer Ronin to Dark Knight. That’s his real masterpiece. There’s a horse in that one too!

Henry, with a story such as Titan (and ‘The Small House’), how do you approach it?

HW: I know Titan is a thriller so I can throw away my cartoony style. Rob writes Dredd with a bit of noir I think it’s fair to say. ‘What would you do if you were Dredd’ type thing. So mood, lighting and lot’s of what-the-hell-do-I-do-now close ups are very important.

Having worked with a lot of Dredd writers over the years, how do you describe Rob’s writing of the character?

HF: Rob is a great writer to work with, not only the where-will-this-go plots but also the emotional description of panels which fires me up. You could read his scripts without artwork and enjoy them just the same. I need to know what happens in this current story arc so pretty much gripped when an episode pops up in my email.

How does the creative collaboration work between you and Henry?

RW: I send the script to Matt Smith. Matt usually offers a note here and there – and they’re usually very good ones as Matt absolutely knows Dredd’s world. But for the most part he doesn’t meddle too much. I think, as we’ve been doing this for a while now, there’s a degree of trust. Then it goes to Henry and often the next time I see it is when it’s in the prog. Matt and Henry have both been doing this so long now, there’s a wonderful machine-like quality about it all. And it works.

Rob, your Dredd writing career began in 2007 and, as with all new writers on Dredd, your first excursions into MC-1 were short pieces. Since then you’ve also been responsible for longer form tales, specifically Titan. Is there a different writing mindset you need to get into when doing short and long Dredds? The economy of storytelling?

RW: The short ones really lend themselves to three act structure. You need a strong high concept. Pages 1-2 will be setup/the world in flux. Pages 3-4 is a goal that needs achieving and obstacles in way. Then a twist, and then a resolution. I enjoy writing them. they’re tight. Get in, get out, no fat on the bones.

Longer ones, the structure can get more fluid, but I do try and stick to that basic template in those six pages. The one regret I usually have is that you have to cram so much into a 6-page Dredd that each page ends up being five or six panels and you don’t get the chance to let the visuals breathe as much as you like. But I do think it’s a page count that leads to a lot of bang for the reader’s buck. You can often get what would be a 20-page story in US comic formats into a 6-page Dredd.

I think the most interesting Dredd stories usually say something about him. If he’s just the cipher/robot – OK, you can have some fun. But there’s not going to be the same character depth or resonance. Wagner did both things so brilliantly, and still does. He can do that fun, quirky, madness of the city thing and he made Dredd this three-dimensional man who could sometimes surprise you. It’s what’s going on below the surface with Dredd that makes him fun to write. Because he’s immensely stoic, and may just offer one word in dialogue but he’s feeling all these things beneath.

That’s why artists like Henry, Chris Weston, and D’isreali are godsends for the writer in this world – so much of writing Dredd is subtext. He says one thing and we know he wants to beat you death below the surface.

Would you agree that, by having these short form Dredd tales, the comic manages to avoid the issues of overly complex continuity found in the Marvel/DC universes and makes it easier for new readers to simply jump into the world of Dredd without hours of extensive research?

RW: Matt Smith’s very good at holding it all together. Dredd’s fairly glacial in continuity shifts but they do happen. And the turnover of new stories by new teams necessitates a ‘you only have to know the basic setup to get this.’ We don’t, by and large, have the big writers’ room conversations regarding Dredd’s world. The only time I can recall something of that was when Day of Chaos happened and Matt sent me and a bunch of Dredd writers some documents that stated Wagner was about to kill off the majority of the city and our stories would need to reflect that. And even that can be summed up pretty quick.

One advantage of the short form Dredds, I’d imagine, is that you don’t necessarily have to concern yourself too much with what other writers have going on. No matter what the disaster that may befall Dredd in a mega-epic storyline, he’ll still always be out on the streets stopping the petty crims and dealing with the weird shit that MC-1 throws up.

RW: That’s largely true. It’s a combined effort from a number of writers. John Wagner still rather owns that world. The big moves are his to make. And rightly so. I remember wanting to blow up Titan at the end of Titan and Matt wasn’t sure because “John might have plans for it.” i argued that the ending needed the stakes. That other writers have to be able to move the world forward somewhat, and we did it. Again, Matt’s the arbiter. He keeps it all running smoothly, week on week.

But, when it comes to creating long form Dredd tales, the writer’s job is a lot harder, I think. With several writers contributing Dredd stories at any point, the bigger storylines have obvious ramifications and require careful planning. And one thing I think happens is that you all carve out your own little Dredd empires, so to speak – there’s Michael Carroll with MC-2, the Sov Sector, Judge Joyce, Judge Dolman and you seem to be casting something of a ring fence around Titan, the SJS Dept, SJS Judge Gerhart, SJS Judge Pin, Judge Smiley and much of the Wally Squad

RW: There’s no ring fence as such, i think it just happens naturally. We all have our own characters and we know them and they suggest certain storylines. Gordon Rennie has a few too. Again, it’s sort of Matt’s role to ensure that no one steps over any lines. If I did have a story idea regarding, say, Dolman, I’d certainly drop Mike a line to run it past him.

Rob, one of your highest profile Dredd tales thus far was ‘Closet’, which garnered a lot of mainstream media attention for its storyline. How did the storyline come about – wake up one morning with the image of Dredd fitting right in at a gay club, perhaps?

RW: I felt that gay culture hadn’t been properly represented in Dredd’s world and needed to be. I wanted to do it in a respectful way, and that was pretty scary to write, as I’m not gay and didn’t want to fall into lazy stereotypes. But i also didn’t want it to be over-earnest. It needed to have the Dreddworld sense of comedy and satire. So that was the line to balance. I think we did it pretty well. The idea of a gay club where people just dress as Dredd was sort of a knowing wink at how bondage-y the Judges can look. The fetishism of the big macho male figure. It drove some rather small-minded readers crazy, which was nice. But at its heart it was about this one kid trying to come to terms with his sexuality. And Dredd and the Judges didn’t arrest anyone for being gay. They arrested people for impersonating Judges.

When did you first discover comics, and what were the comics that made you fall for the artform?

HF: My first comic was Jack and Jill when I was 3-4 years old then later had a big thing for Buster, Whoopee and Whizzer & Chips, I’d buy them and others alternately. Then went through a MAD magazine phase and after that got into European and underground comics, incredibly difficult to get any information about in those days. No computers back then you see. It wasn’t until a visit to Forbidden Planet when I was 14 that I discovered American comics and thought perhaps I’d been going in the wrong direction. No idea why I fell for comics, they just made sense.

RW: I honestly can’t remember. Someone gave me some DC comics – All-Star Comics with the JSA (I still have the issue, although the cover never survived) and an Adam Strange Justice League issue. A Neal Adams Green Lantern that, again, has lost its cover. A neighbour from up the road would give me her son’s Victor book for boys every week when he’d finished reading it. I’d read Roy of the Rovers, Whizzer & Chips, and eventually 2000 AD. I sort of always remember loving comics.

And similarly, when did you first pick up a 2000 AD?

HF: It was Prog 1, 2 and 3, then a big gap. Mum thought it too violent, tee-hee.

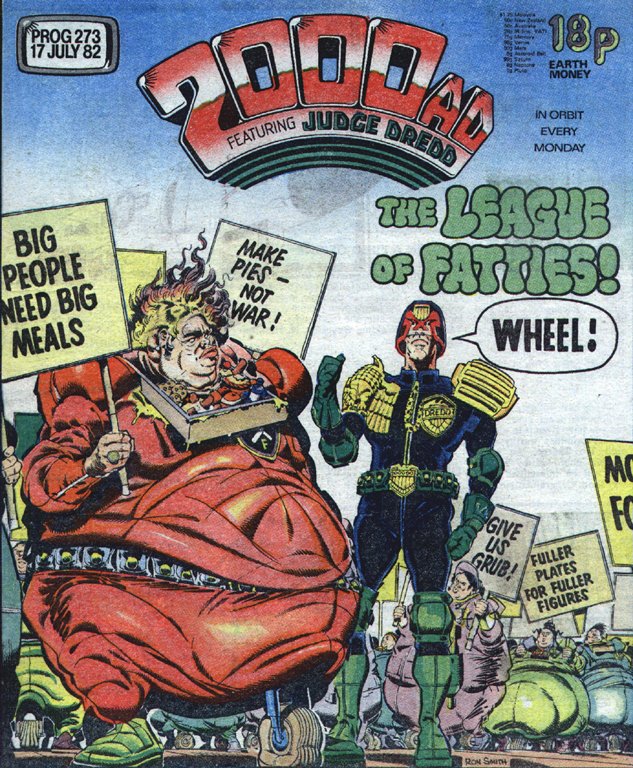

RW: My first weekly ordered Prog was the Ezquerra one with Dredd and the Fatties ‘Umm. Synthi-sausage’… What was that? ’83. So I can’t say I was there at the start. My mate Martyn was getting Starlord and I have very vivid memories of reading Ro-Busters and Strontium Dog round his house.

What was it about 2000 AD that really turned you into a fan?

HF: You know those little boxes which read ‘Thrill 4’ with a picture of a gun or a dinosaur underneath, those. A perfect hook! Massimo Belardinelli and Kevin O’Neil were my favourites in the early days.

RW: The enormous amount of hyper-violence. That’ll turn a 12-year-old’s head.

Was there a moment you thought “one day I’ll be in 2000 AD rather than reading it”?

HF: Yeah, when Liam Sharp started drawing for the comic and I thought wait a minute he’s only a few years older than I am.

RW: It was never my plan really. I was a freelance journalist in my mid-twenties with no real definite thought of trying to write comics for a living. I sent off a couple of Future Shock ideas. Got turned down. But growing up, it never struck me that it was even possible to be a comic writer for a living.

Can you give us a little insight into how you broke into comics?

HF: I first worked at King Rollo studios colouring animation cells. Then a few comics for Tundra which saw print in Heavy Metal magazine. Then worked for Marvel UK on Death’s Head and four issues of Kill Frenzy which never saw print due to Marvel UK’s cut backs. Then with a reasonable portfolio moved onto 2000 AD.

RW: I went to my first comic convention at Bristol because I lived there at the time. Saw an advert in the local comic shop. Probably Forever People up on Park St. I’d written a script for what would become Cla$$war. Full script, no pitch. I had no idea. I gave that to Com.X at the convention and a few months later they rang and said they wanted to publish it. After Cla$$war came out, I was at a comics drink up in London and Andy Diggle was there. He said “you should be writing for 2000 AD.” That was my way in.