The Treasury of British Comics archive encompasses not just the largest collection of English language comics in the world but also more than a century of publishing of all kinds. In his regular look at classic British comics, David McDonald focuses not on one title in the archive – but all of them…

Since launching in 2016, the Treasury of British comics has brought us a plethora of classic comic collections from their archive. At the bottom of this very page, you will see it proudly proclaimed that The Treasury of British Comics is ‘The world’s largest archive of English-language comic books’.

I wonder have many ever actually considered how vast this archive actually is?

While we have all been enjoying reprint collections from the sixties to the present, these just represent the tip of the iceberg of material from that era and, in turn, that material is just the tip of the iceberg of the complete archive.

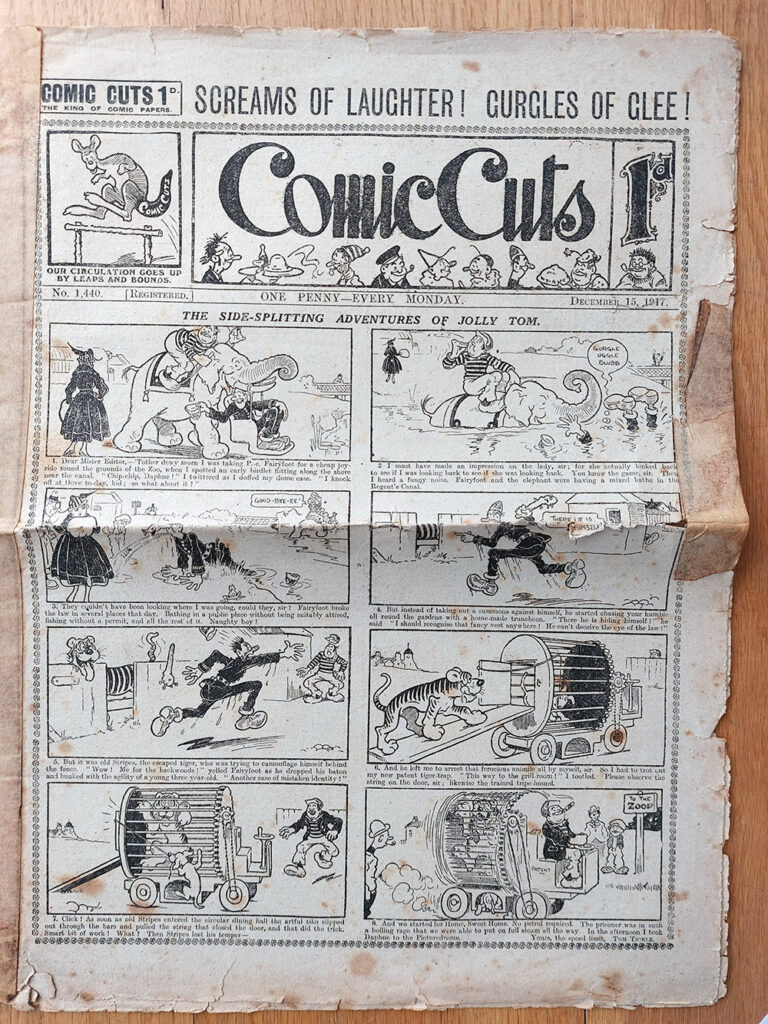

To get an idea of its size we need to go back to the late 19th Century and the burgeoning publishing empire of Alfred and Harold Harmsworth, who first published Comic Cuts in 1890. The Harmsworth brothers were publishing pioneers, taking advantage of the increasing reading ability across the population to launch cheap reading material.

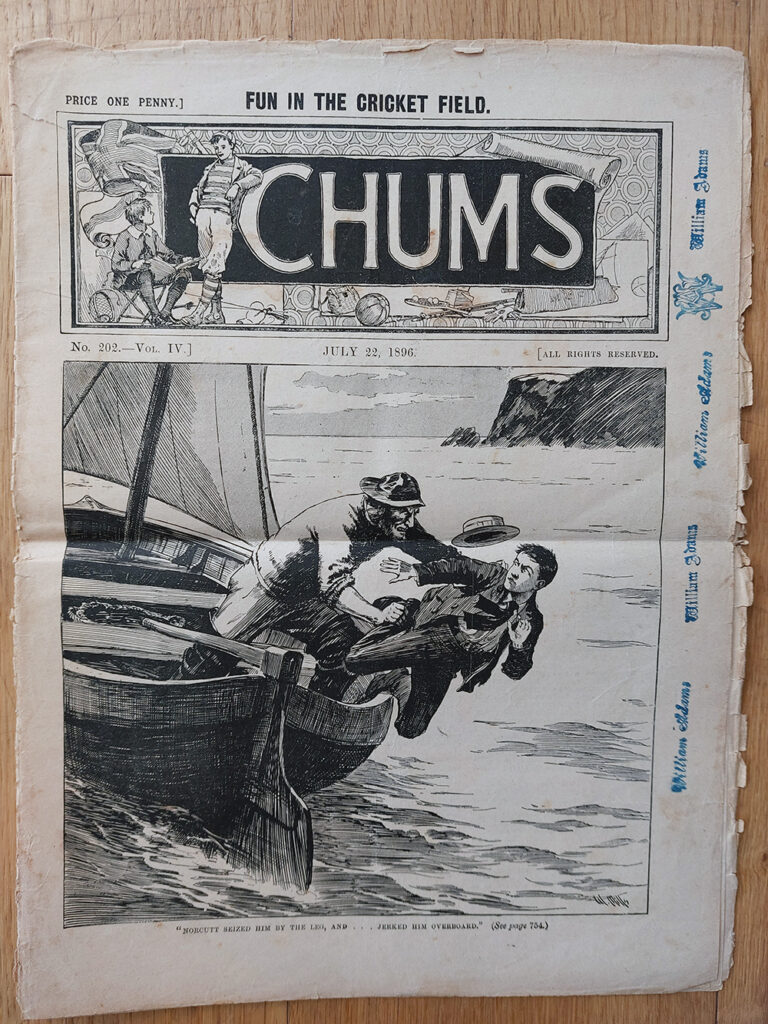

The late 1800s saw them launch titles aimed at various demographics; boys story papers, women’s magazines and even newspapers, the ‘Daily Mail’ being one! A routine issue of The Halfpenny Marvel, issue six in December 1893, was one of their most important releases of the time, but more of that later.

In 1901 Harmsworth consolidated their various publishing interests into a single entity called ‘The Amalgamated Press’ and in 1912 the company moved into a building called ‘Fleetway House’.

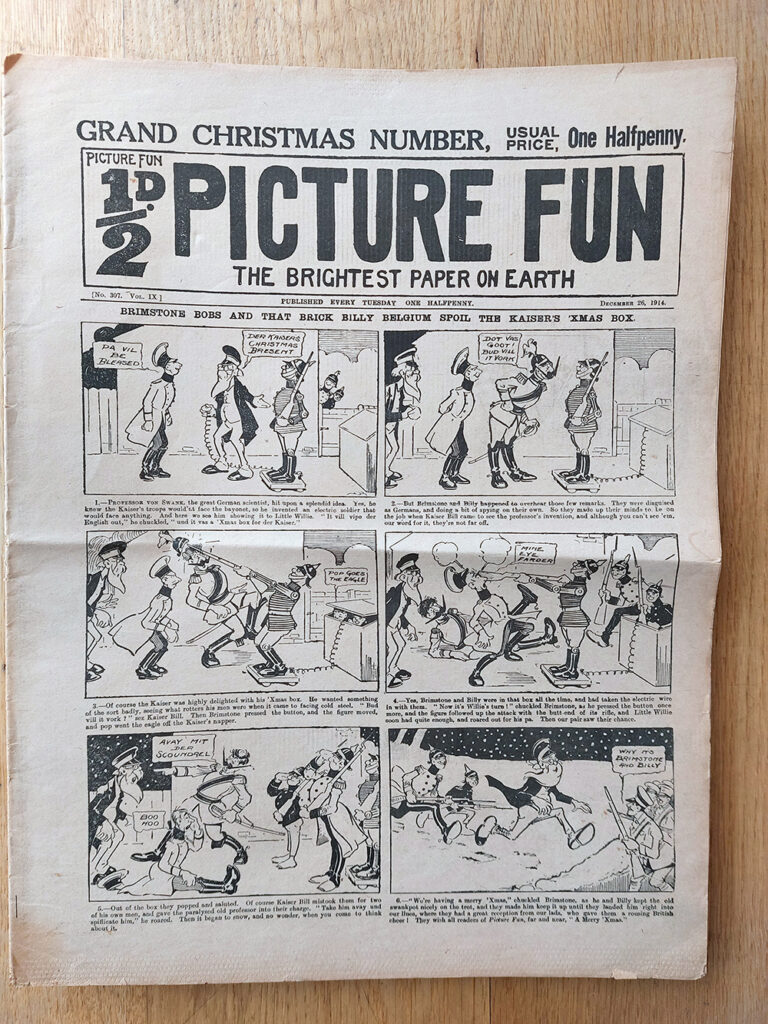

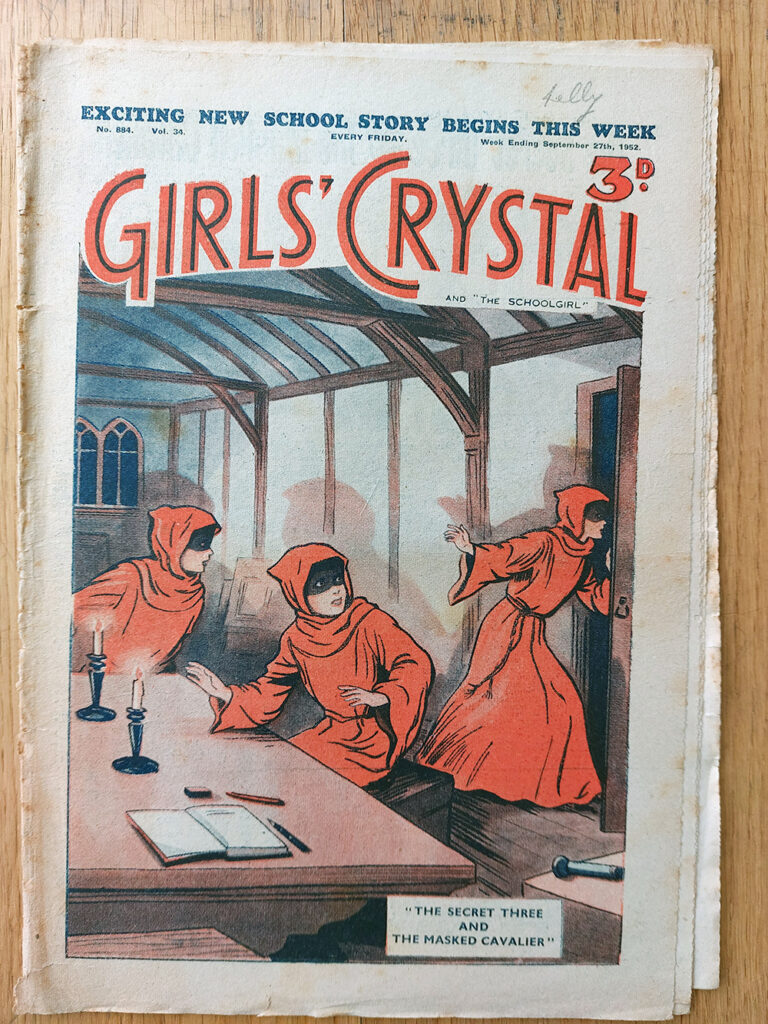

From 1901, The Amalgamated Press launched waves of titles aimed at every demographic, nursery, boys, girls and general interest. There was a range of different formats too, from paperback pocket books to story papers – which contained serialised novels and short stories – to A3-size comics and magazines. Over the following decades titles would be cancelled after reaching their natural end and fresh titles launched that reflected the style and trends of the times.

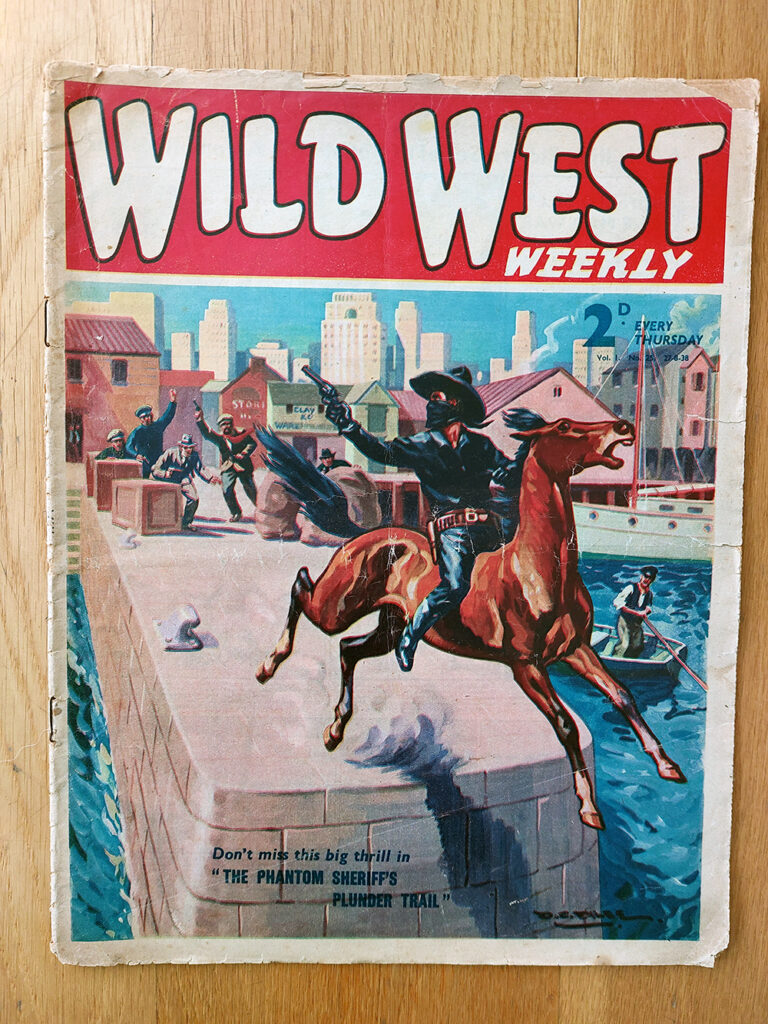

The publishers were not averse to jump on current trends, launching Film Fun in 1920. This coincided with the rise in popularity of cinemas. Similarly, Radio Fun was launched in 1938 when the radio stars were starting to enter the kitchens of houses around the UK and Ireland.

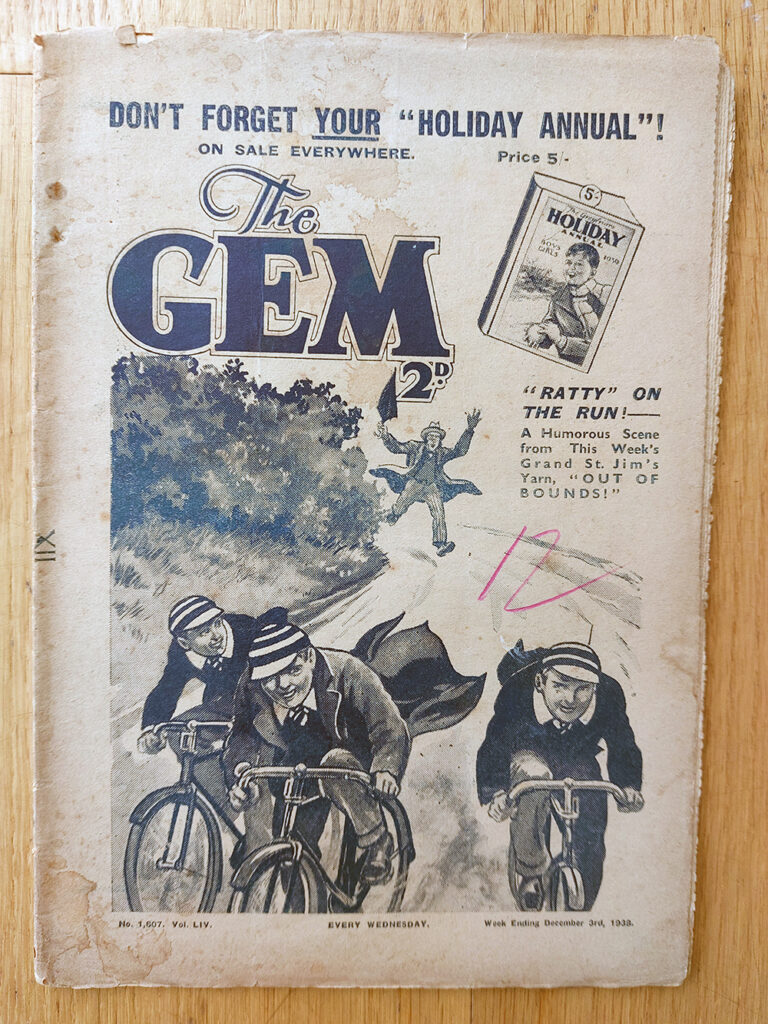

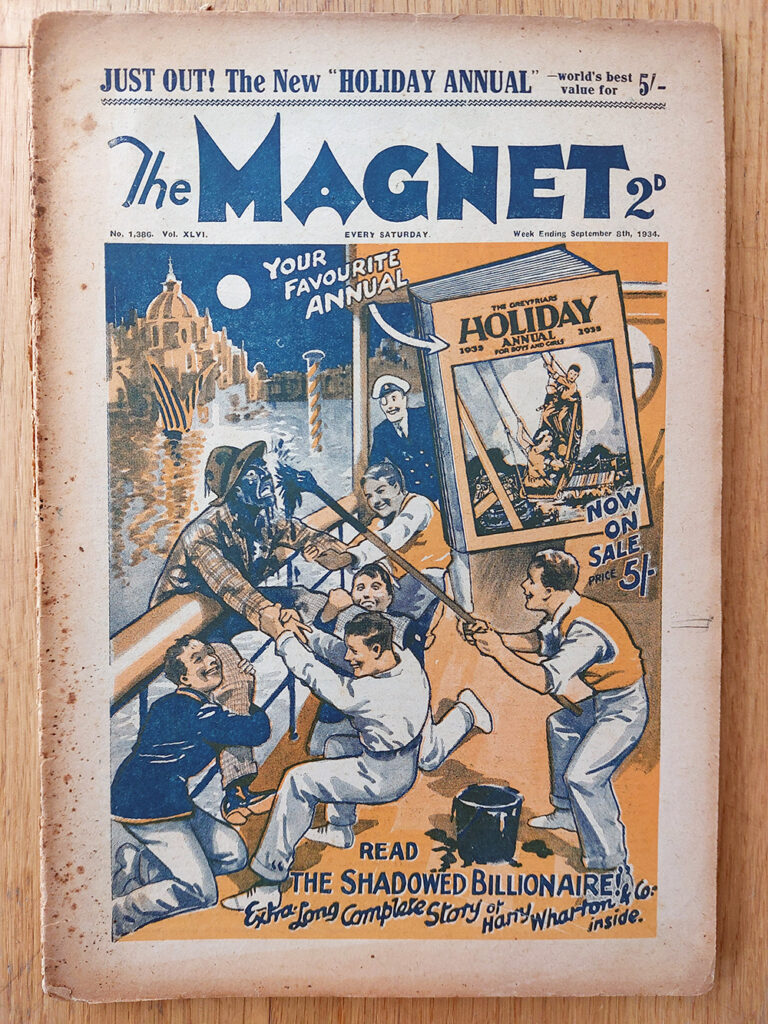

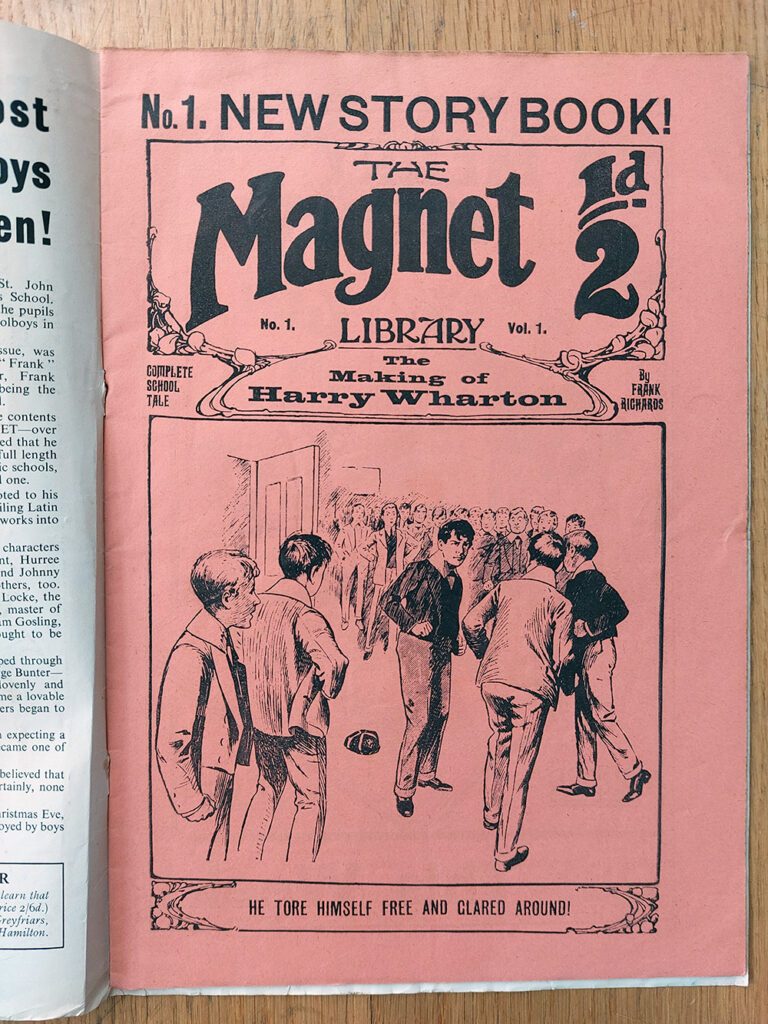

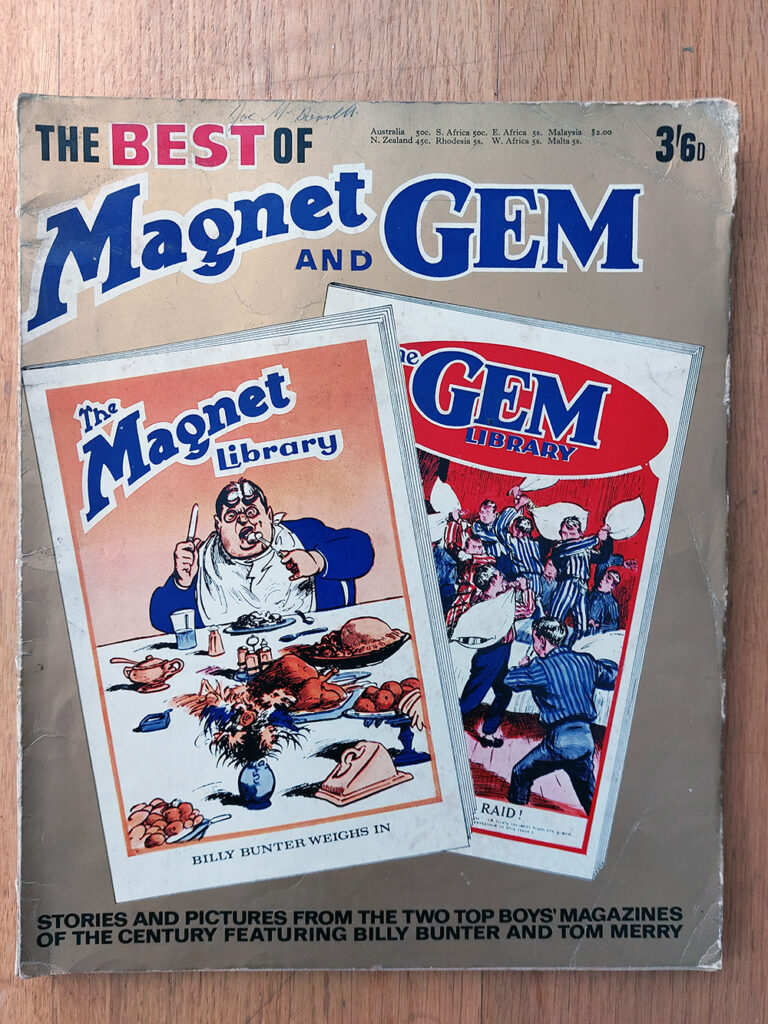

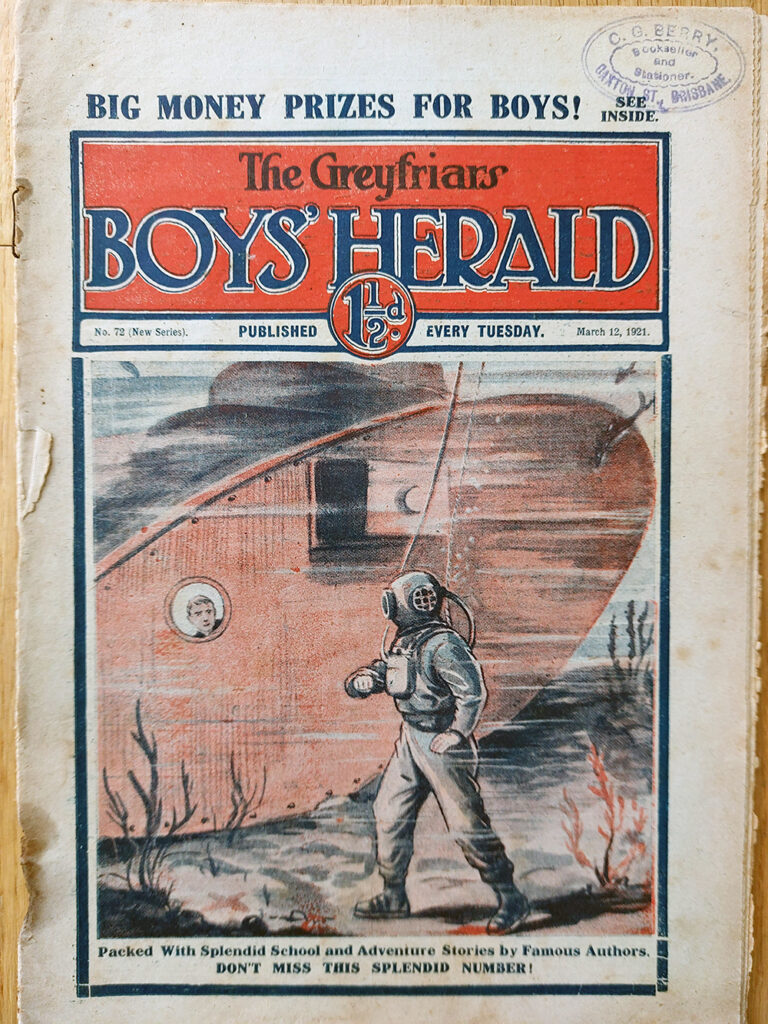

‘Billy Bunter’, ‘Greyfriars’ and the phenomenon of boarding school stories, which was a firm middle class aspiration for many, proved a great selling point for big-selling titles like The Gem and The Magnet when they launched in 1907 and 1908. ‘Bunter’ creator and author Charles Hamilton built his reputation on these titles as the world’s most prolific author. Boarding school stories also appeared in girls’ titles like School Friends/Schoolgirl. ‘Bunter’ and ‘Greyfriars’ also made the leap to the new mass media with adaptations for radio and television.

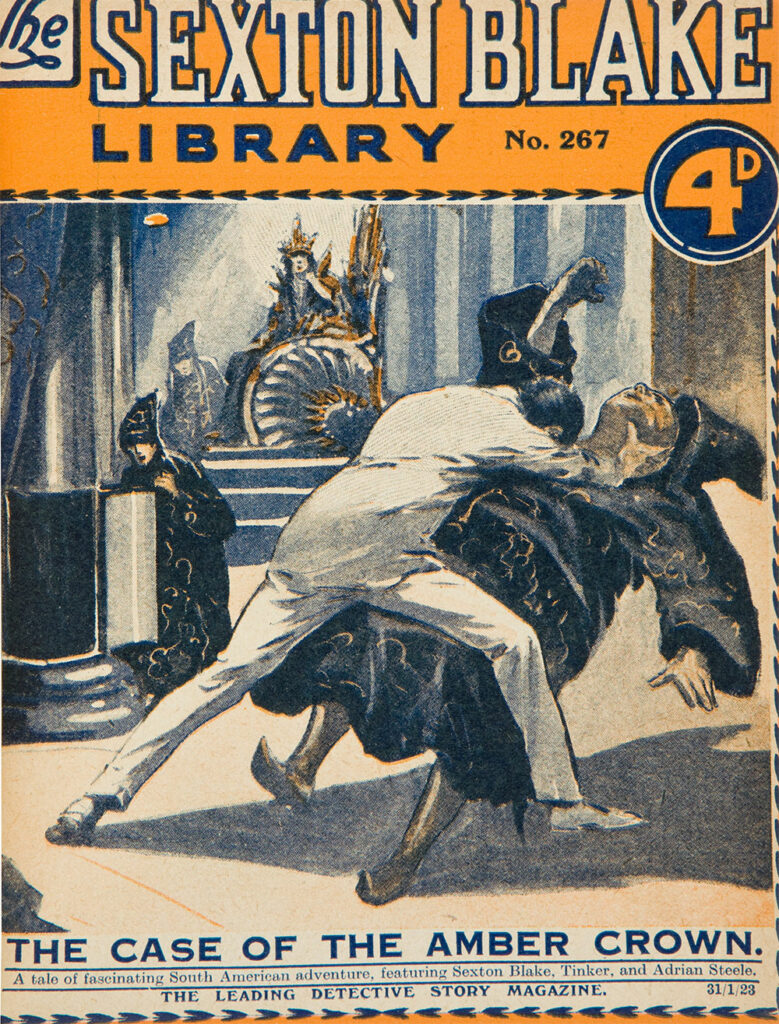

Going back to issue six of the Halfpenny Marvel from 1893, the importance of that issue was the introduction of The Amalgamated Press’s most important character and major asset for the first half of the 20th Century: Sexton Blake.

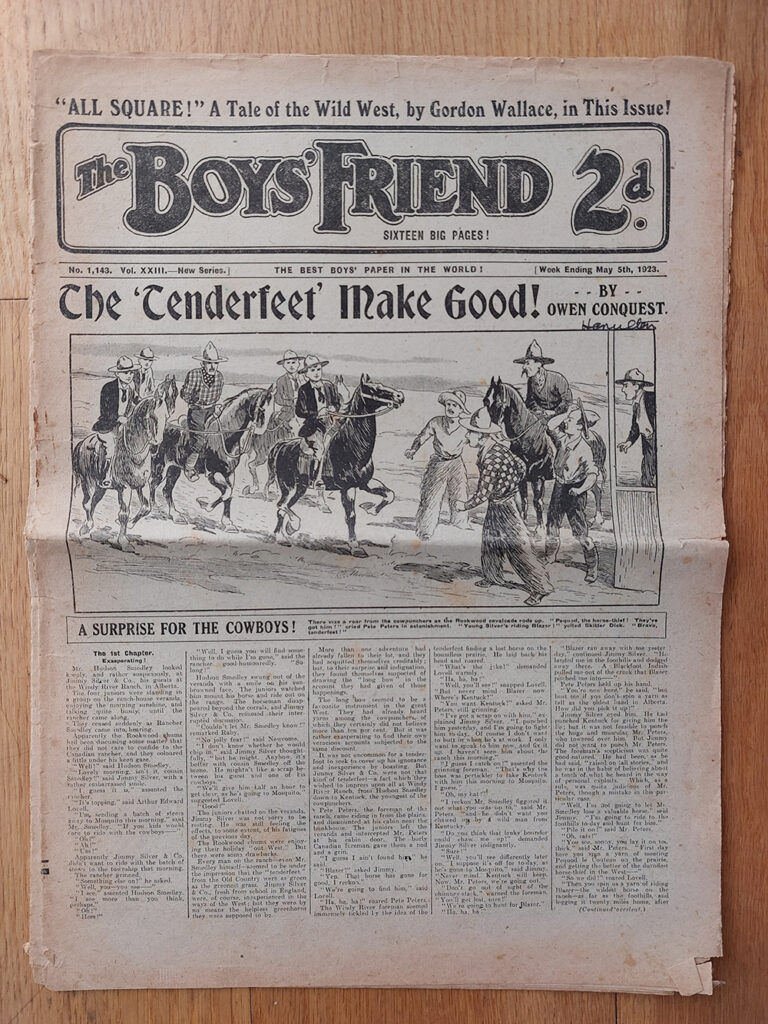

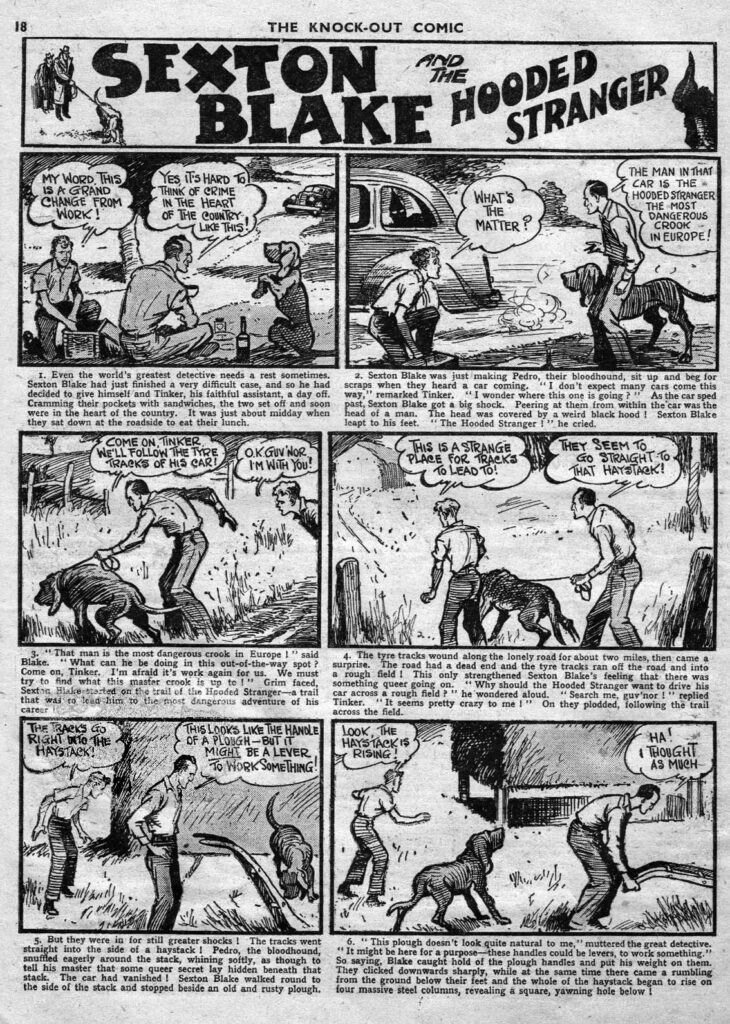

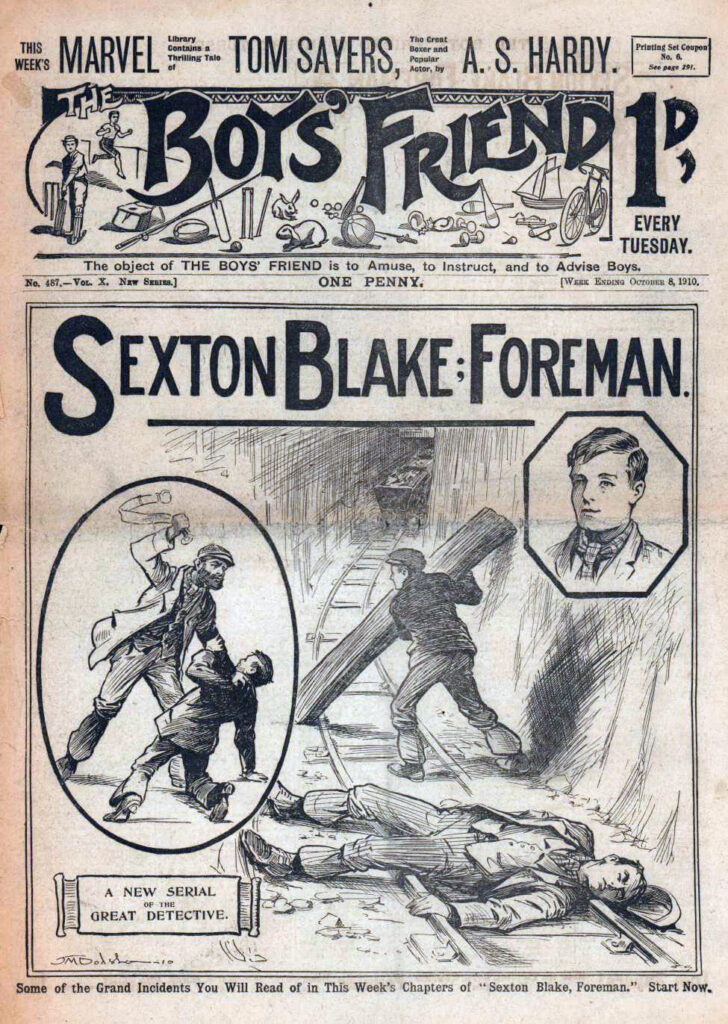

Blake was the star of the Union Jack story paper, but he also appeared in Illustrated Chips, The Boys Friend, Marvel Library, Sexton Blake Library and many others. These were all text stories, but he would later appear in Knock-Out and Valiant in comic form.

Blake was big business for AP, with his exploits selling in the millions and also transferring to stage, radio, and screen. Blake was also one of the longest characters in print, published from 1893 to 1970 (there are reprint titles after 1970, but these were not published by IPC).

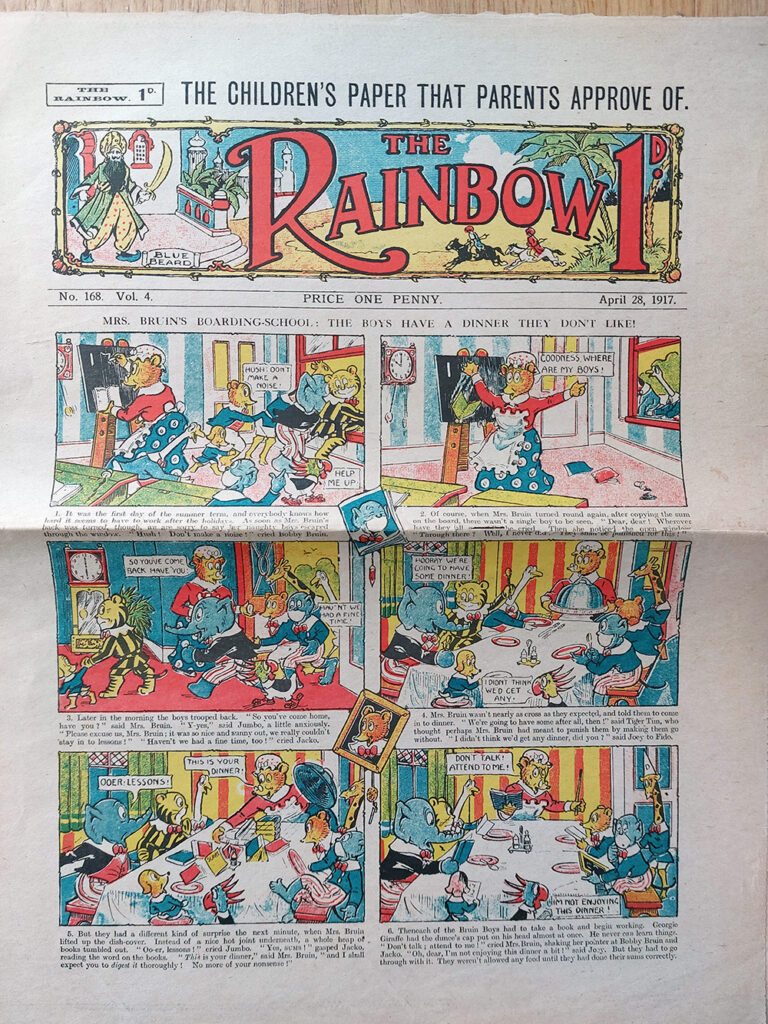

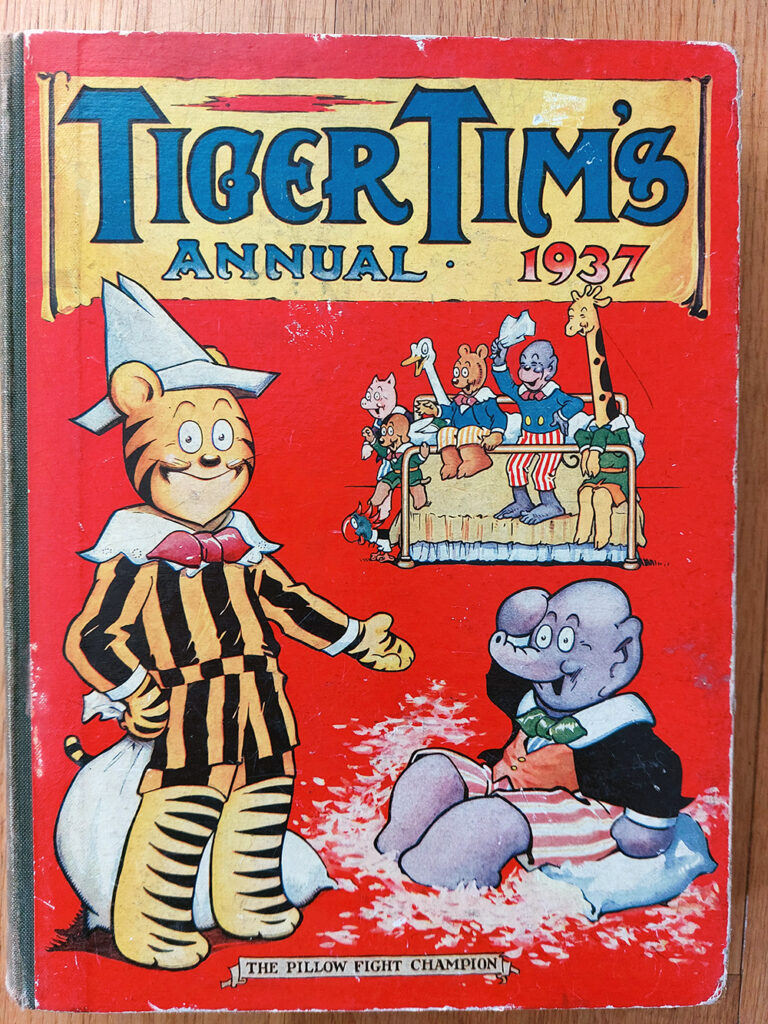

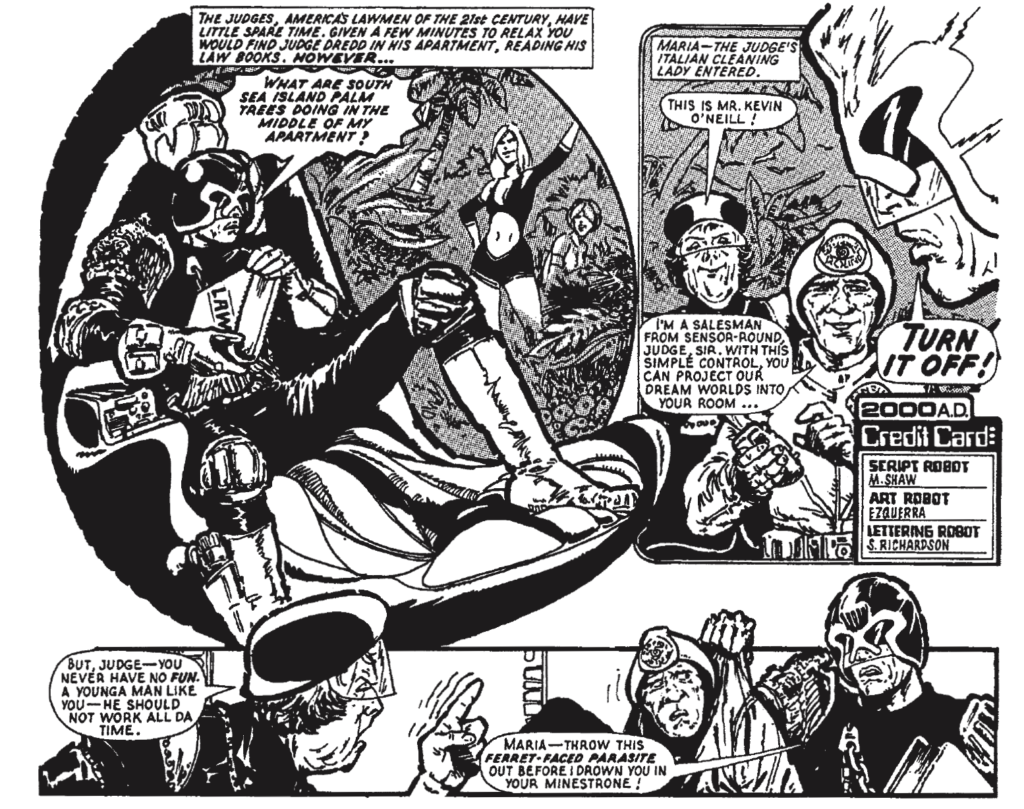

However, while Roy of the Rovers and Judge Dredd are catching up, they all have a bit to go before they beat the longest-running character in the archive – the nursery character Tiger Tim, who first appeared in the magazine The World & his Wife in the late 1800s, then in Rainbow and Tiger Tim’s weekly, right up to the 1980s in Playhour.

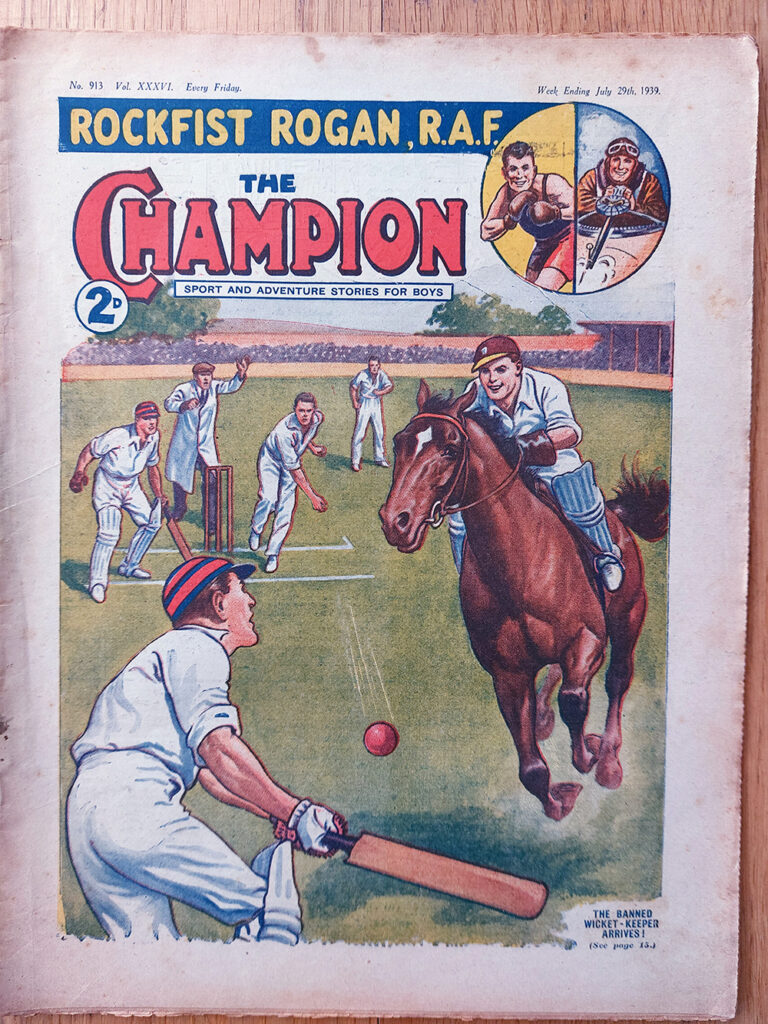

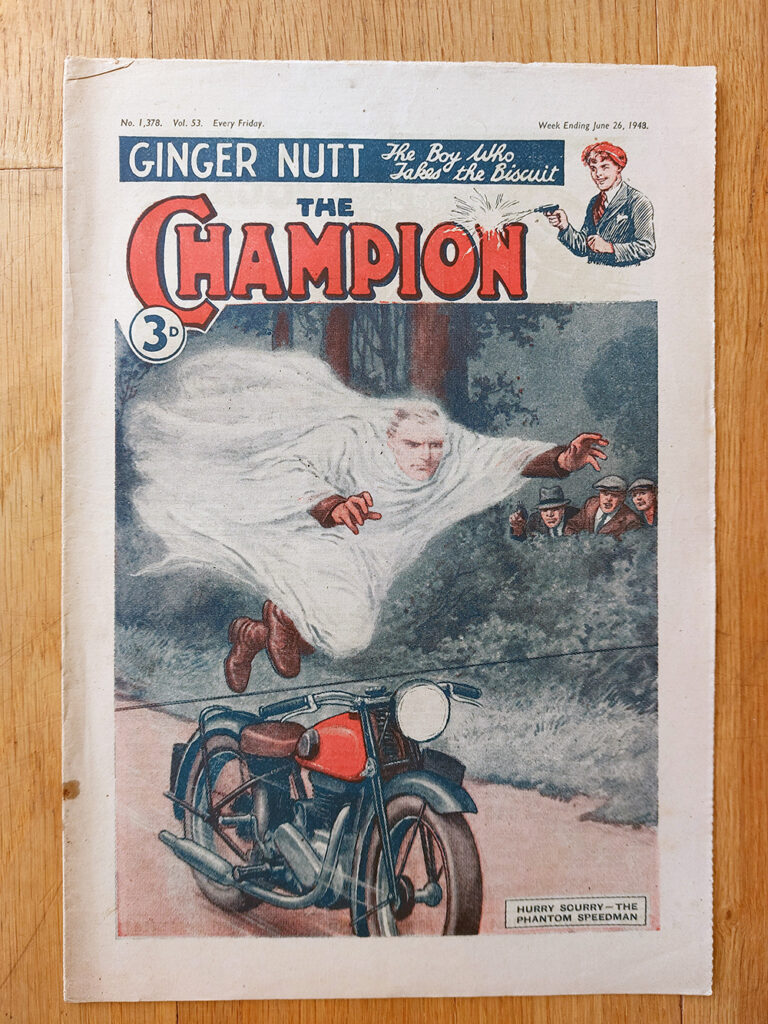

Wartime brought its own difficulties to the publishing world. From 1939 to 1946 the story paper ‘Champion’ went from 28 pages to 16, lost its colour cover, was reduced in size by a third, and increased in price by 50 per cent! Paper shortages and inflation meant Champion did well to survive the war; other titles were cancelled, but AP did re-launch War Illustrated to some success, which had also been published during the Great war.

Along the way, The Amalgamated Press absorbed other companies like ‘Traps Holmes’ ‘Cassells’ and ‘J.B. Allen’, and then in 1959, The Amalgamated Press itself was taken over by the Mirror Group and renamed ‘Fleetway Publications’. Fleetway saw a range of new titles, reflecting the changing times.; Buster and Valiant were launched, Lion and Tiger were updated, and titles like Knock-Out and Radio Fun were cancelled.

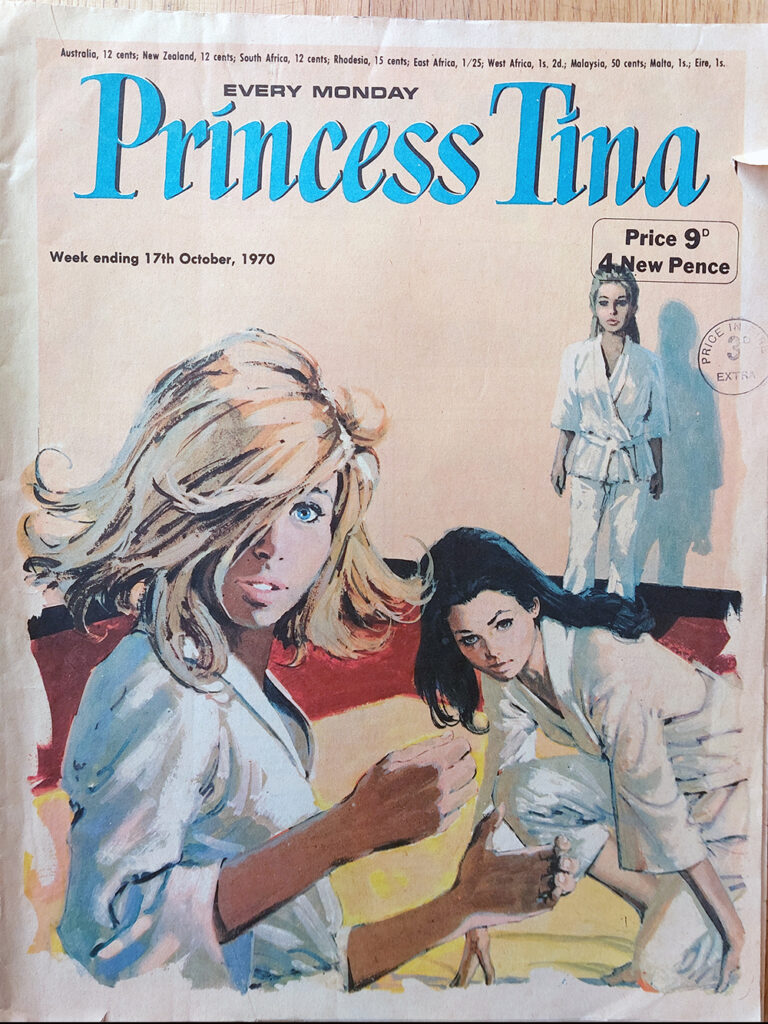

Picture libraries started in the fifties and, under the Fleetway banner, expanded to be an important part of the publisher’s output in the sixties and seventies. Romance titles that had started in the fifties also found success in the sixties, morphing into the girl’s teen magazines like Pink and Mirabelle in the seventies.

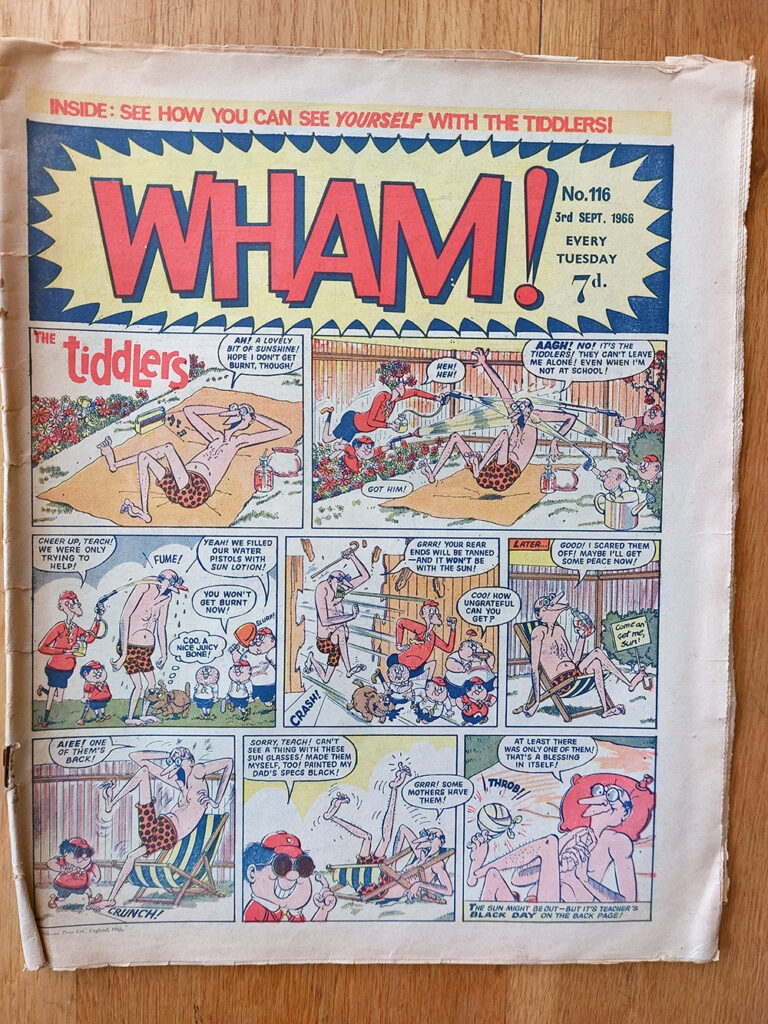

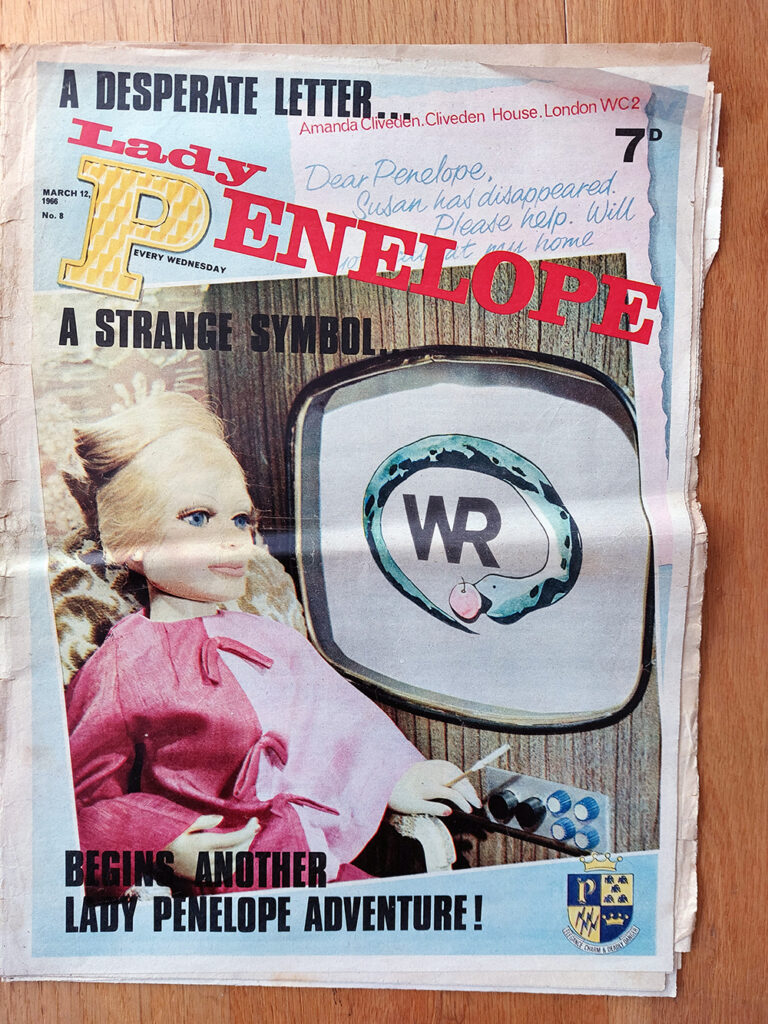

The Mirror Group also purchased the publisher ‘Odhams’ (which itself had previously bought publishers ‘Hulton’ and ‘Newnes’), creating the company IPC in 1963. The merger with ‘Odhams’ brought its Power line of comics like Smash, Pow and Wham into the archive. Later in the sixties, some of ‘City Magazines’ comics like TV21 and Penelope also became part of the archive.

In 1968 all the various entities publishing comics owned by IPC, such as Fleetway and Odhams, were consolidated and renamed IPC Magazines. At this stage IPC was reckoned to be the biggest publisher in the world.

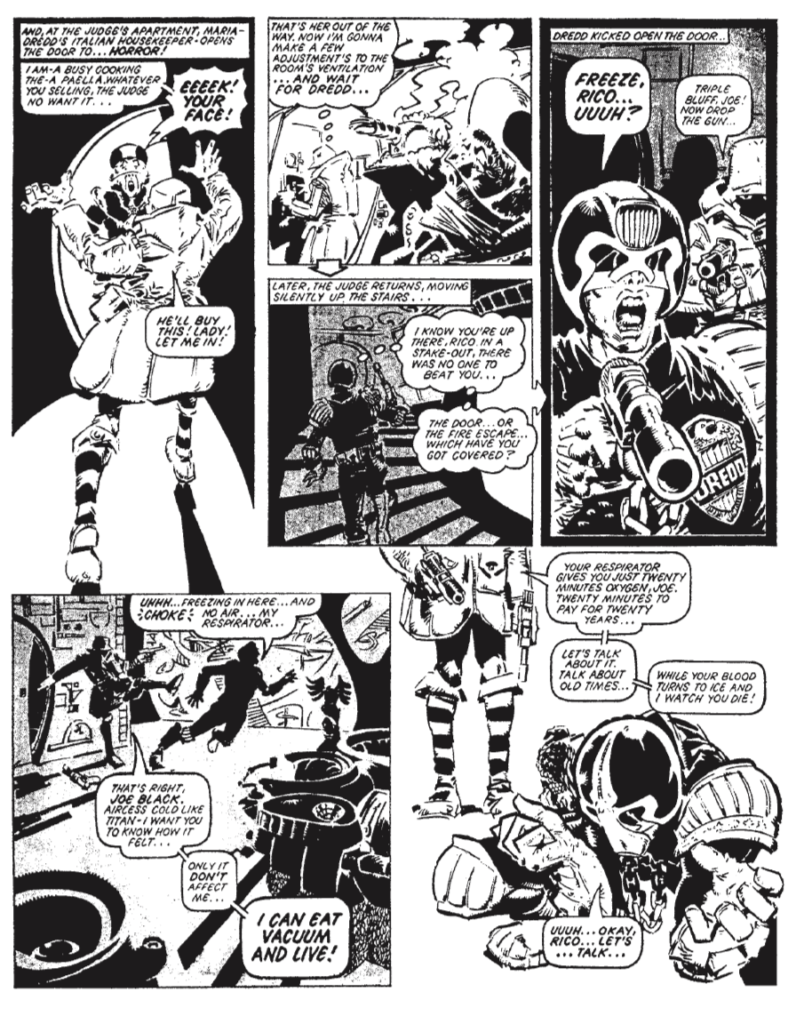

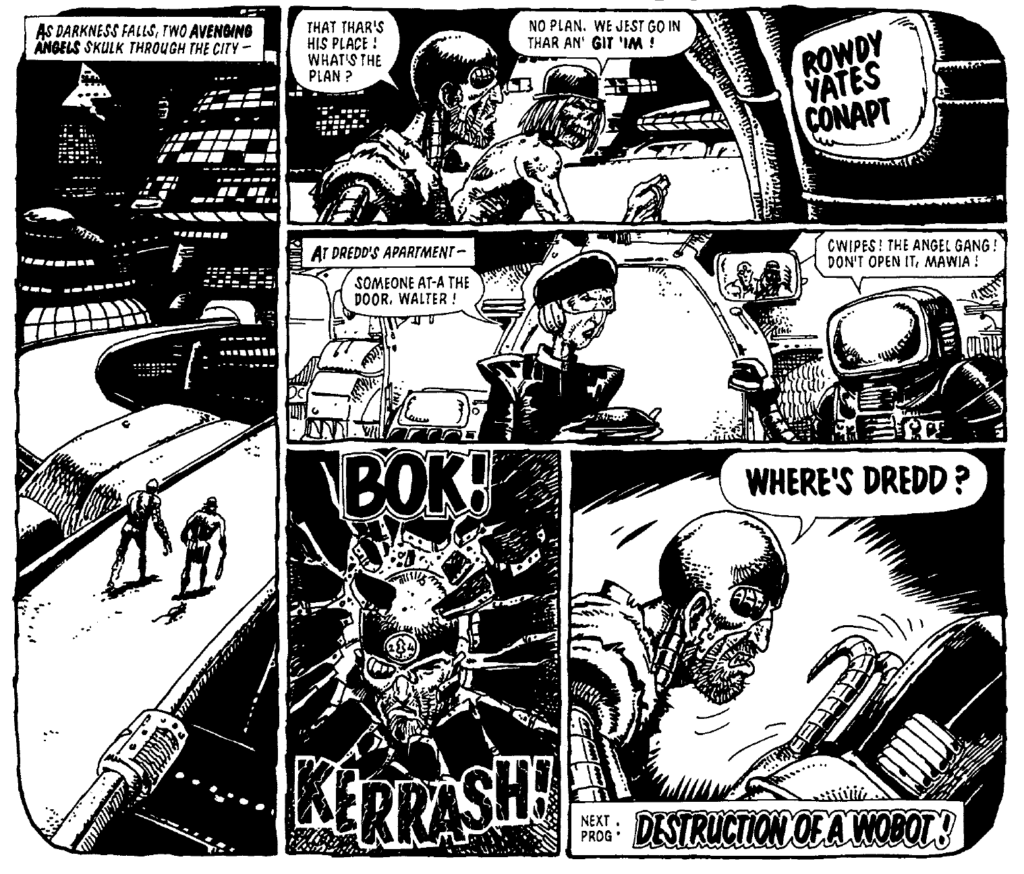

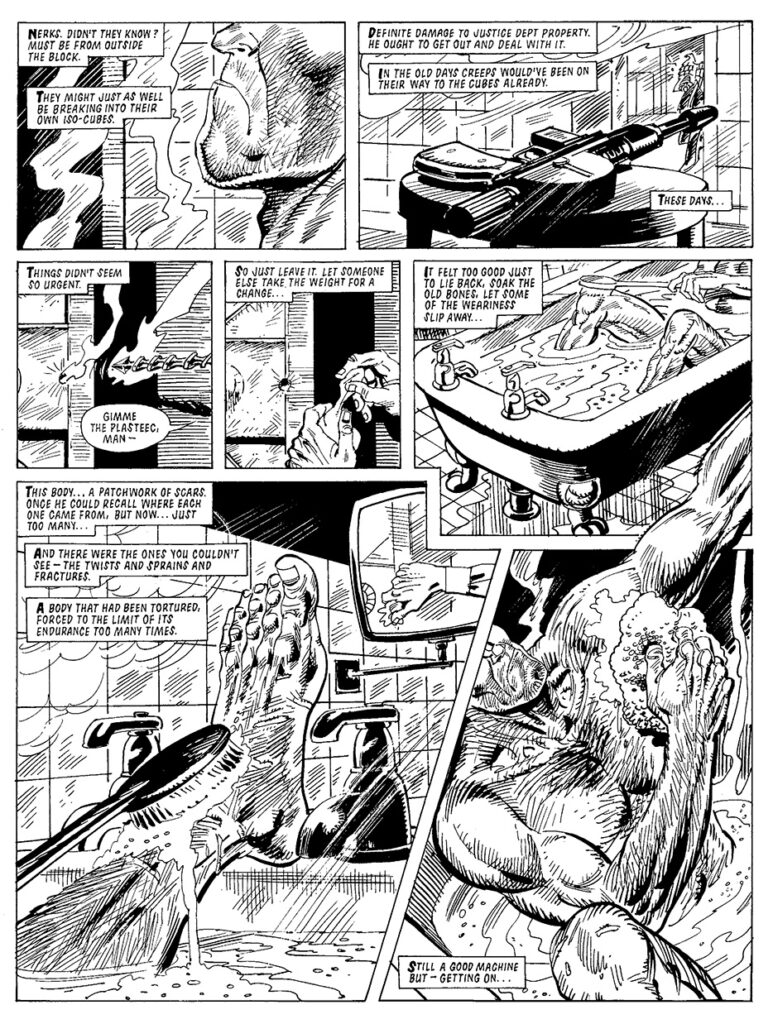

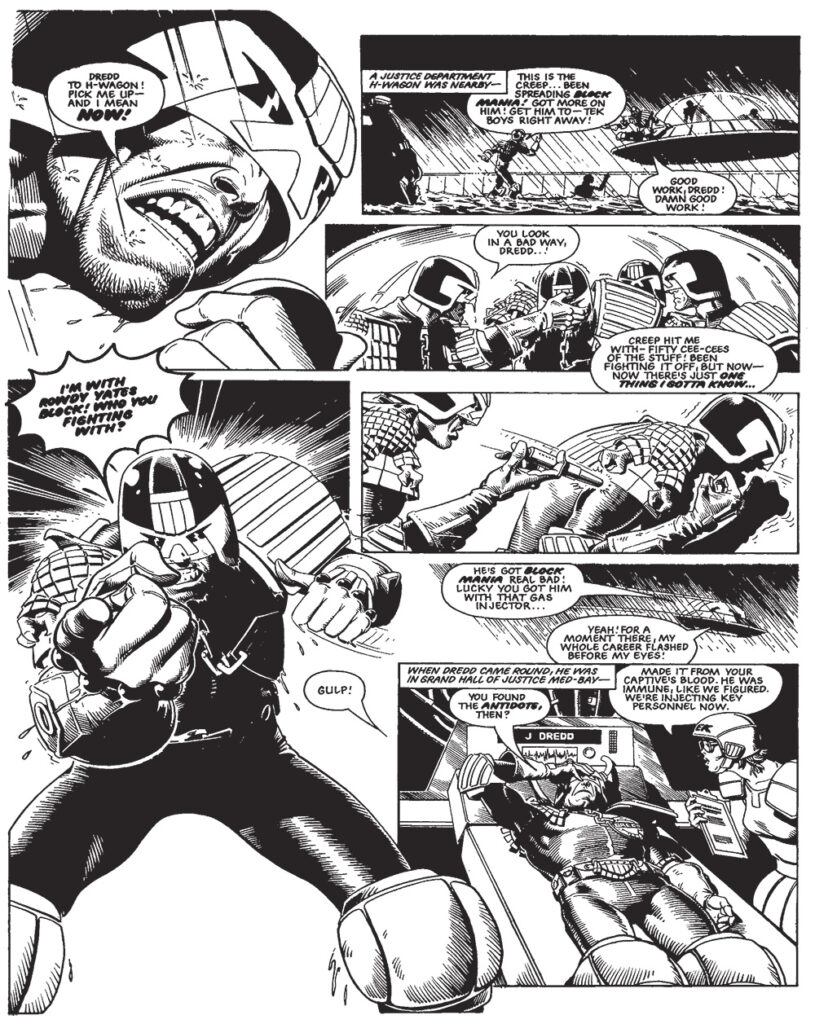

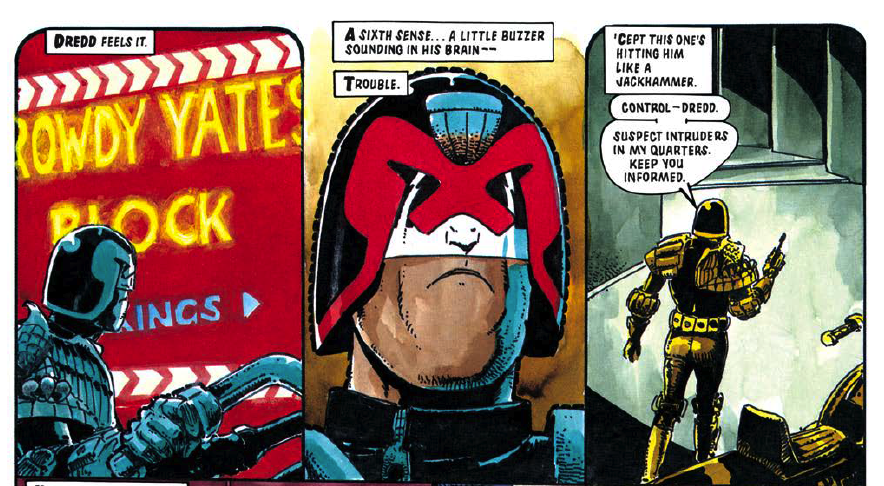

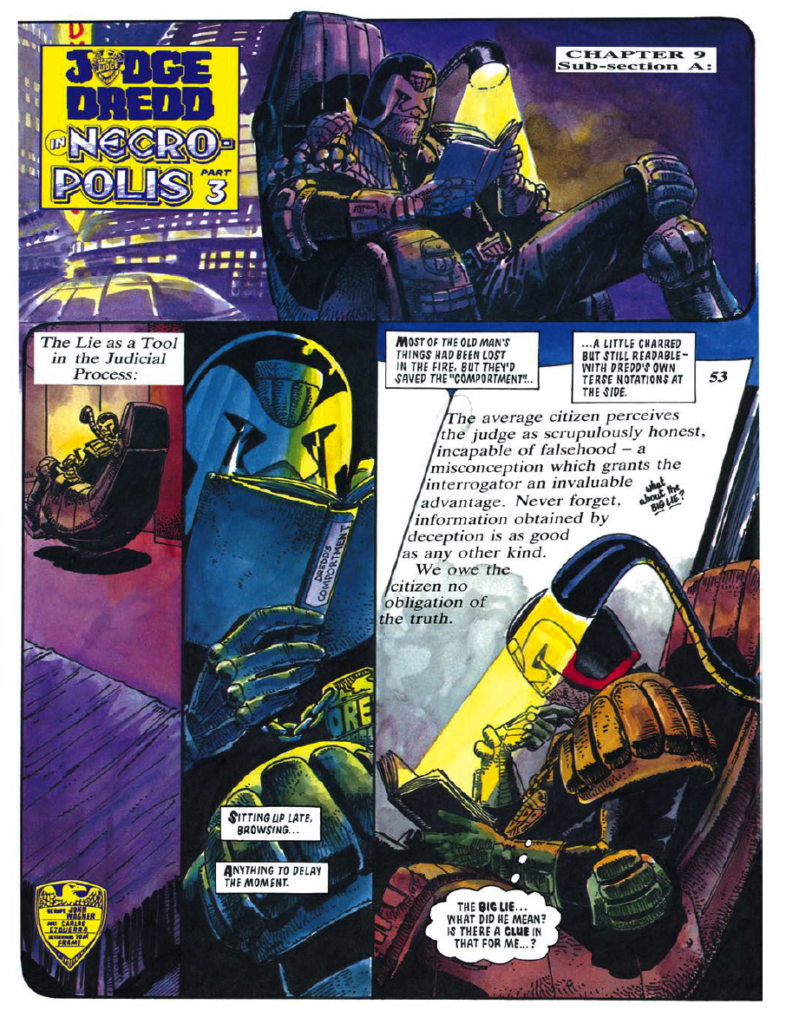

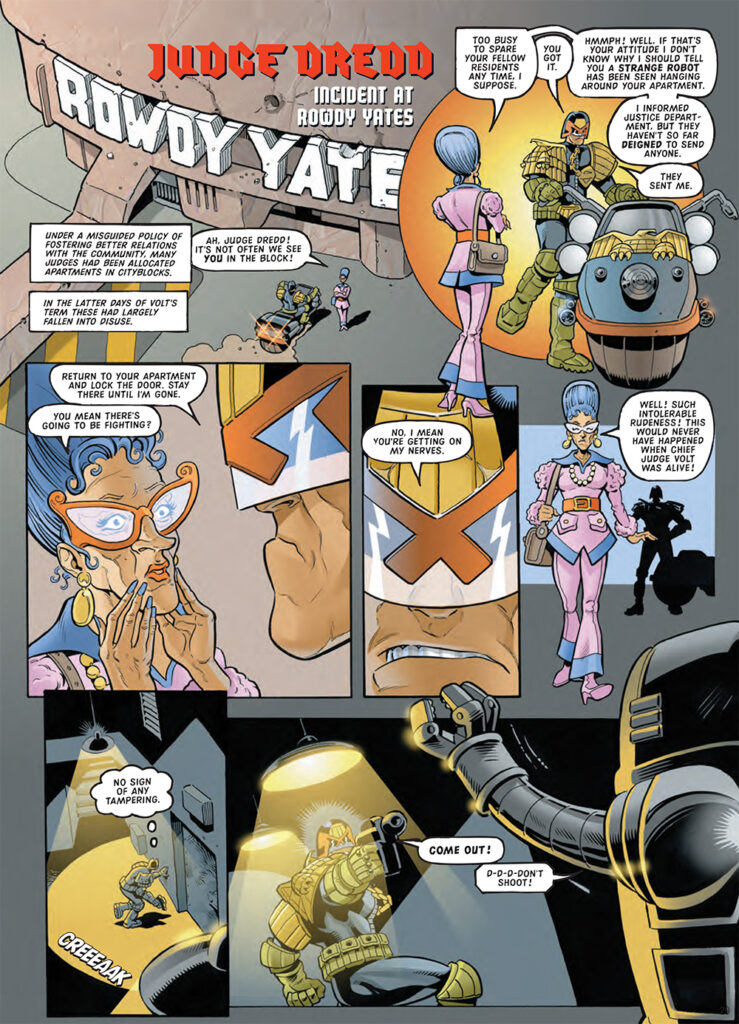

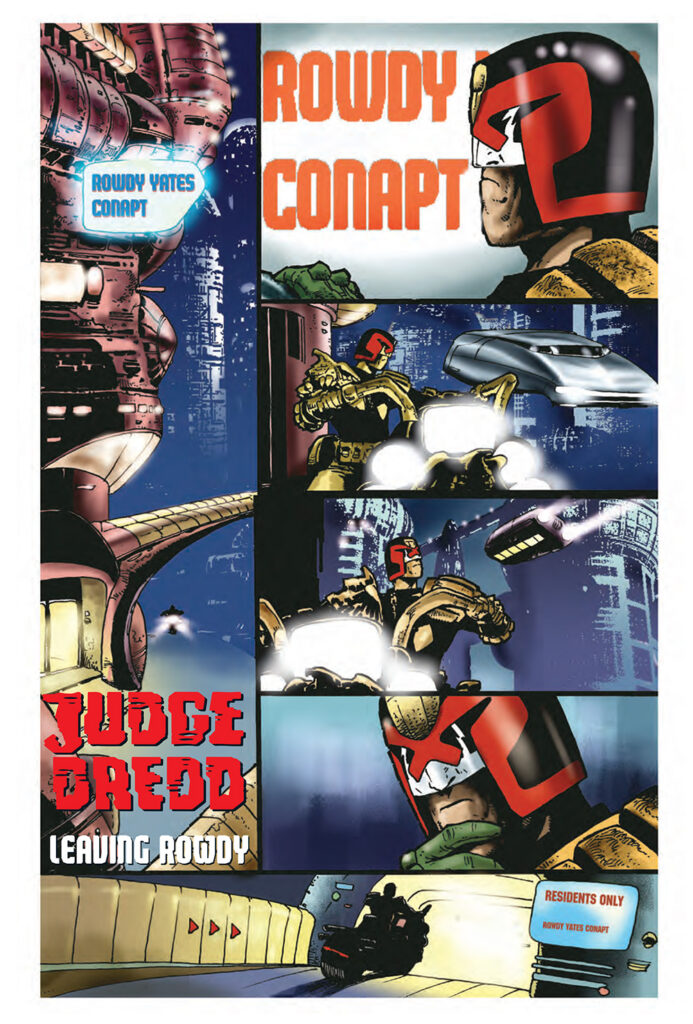

IPC Magazines brought another slew of titles to the archive, with a line of humour and girls’ titles starting in the seventies, as well as Action, Battle, 2000 AD and Starlord. The seventies are seen as one of the golden ages of British comics.

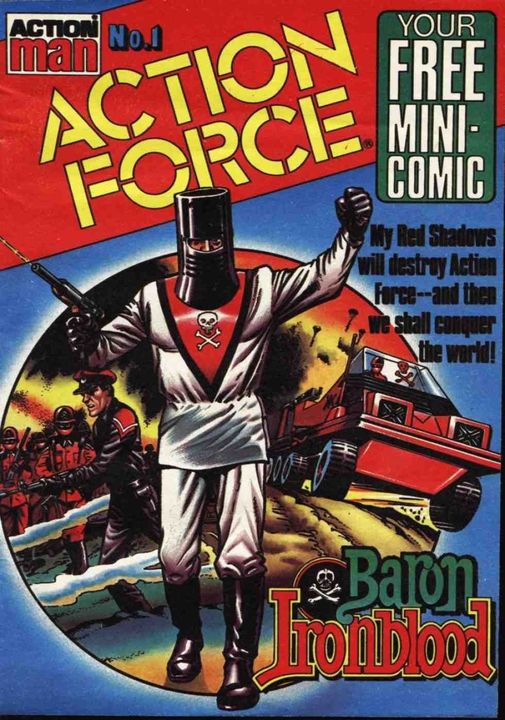

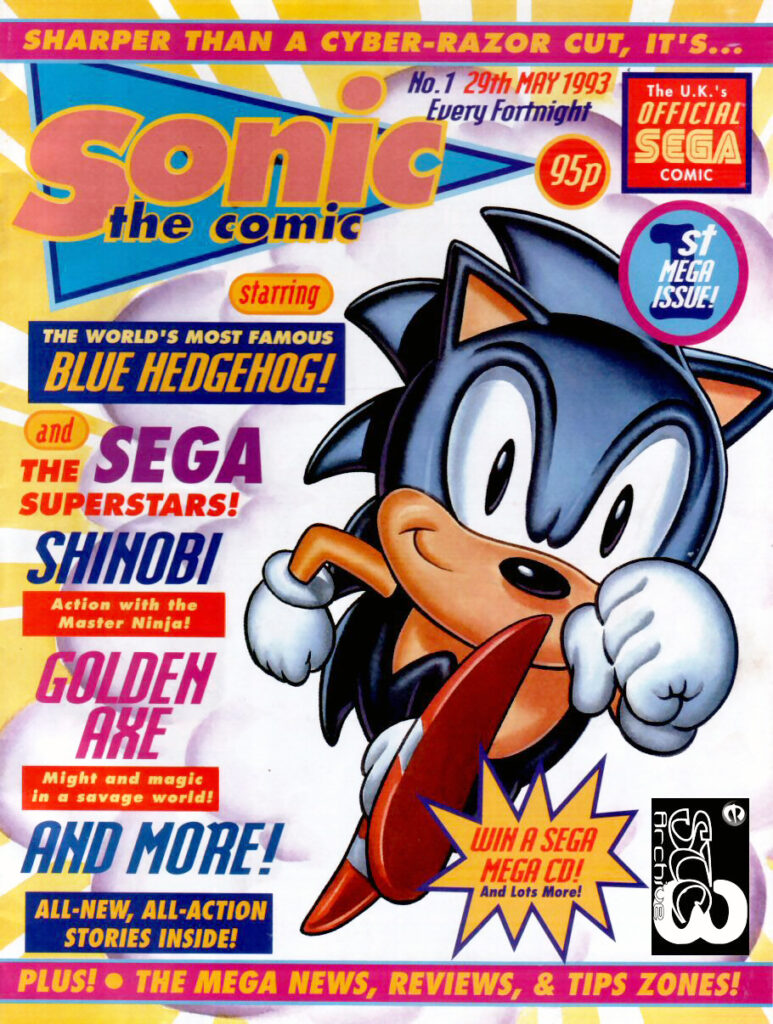

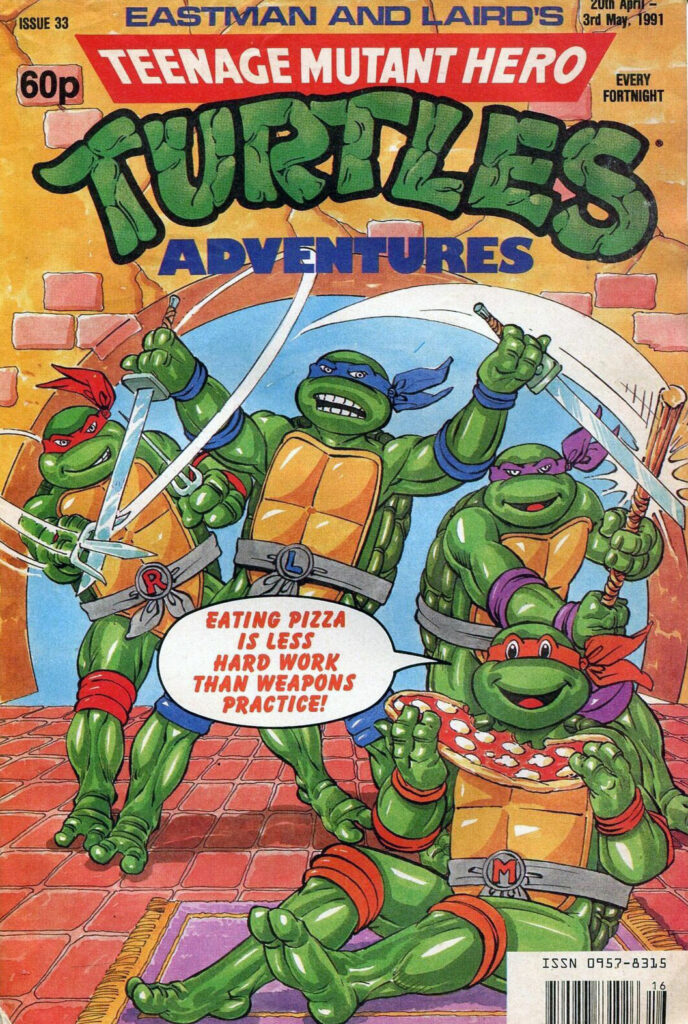

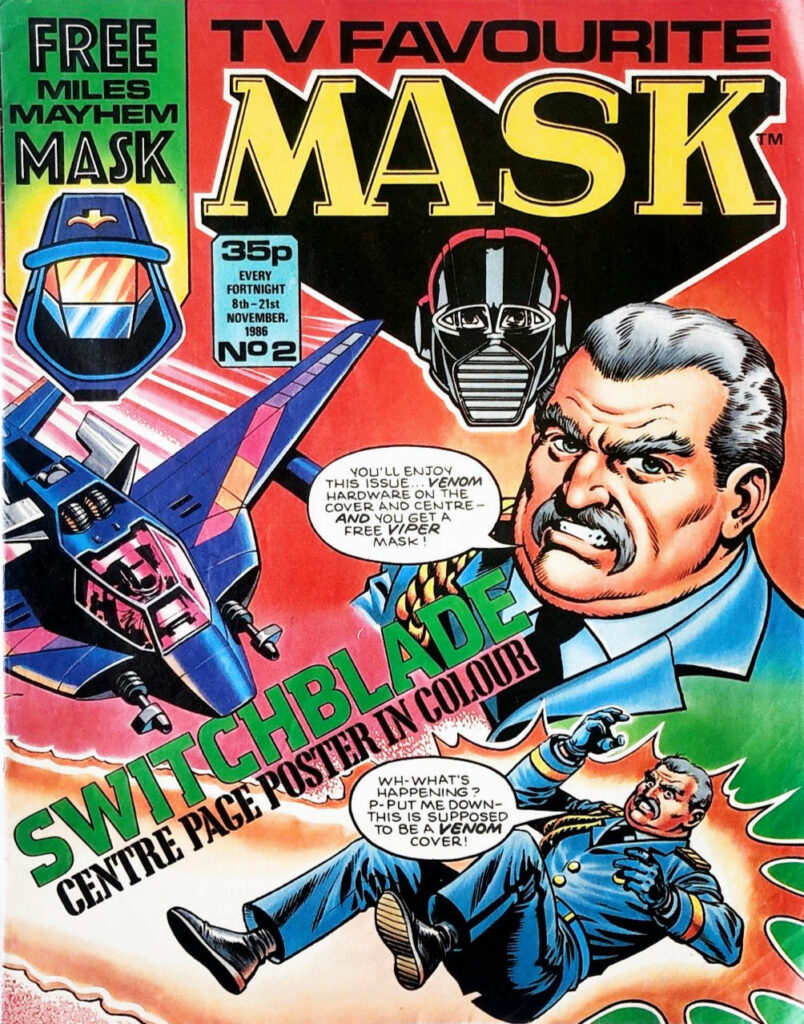

The late eighties and nineties are well documented for the decline in the traditional British comic market, but it did bring a new type of comic to the archive. Licensed comics like Action Force, Mask, Sonic the Comic and the million selling Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles are all there.

To get a grasp on the actual amount of material contained in the archive, consider five of the titles with the longest longevity in the archive over the last century or so: 2000 AD, Comic Cuts, Illustrated Chips, The Champion, and War Picture Library. These have a cumulative total of nearly fifteen thousand issues, and an estimated quarter of a million pages!

That figure is only for five titles, the true number of individual titles in the archive is in the hundreds – and this is not just comics and story papers, but also includes non-fiction, magazines and novels.

The actual page count is in the millions.

The importance of this archive goes far beyond the very enjoyable collections of classic characters’ adventures.

A major part of the archive is from a time before the proliferation of the smartphone, the internet, television and even radio. Print was the social media, the Google of its day. So, in addition to the sterling adventures, laughs and romance contained in the archive, there is also a glimpse into social attitudes and norms, political mood and the changes in them over the decades. It gives a fabulous insight into the war efforts and how it was used as a very effective propaganda tool. It also charts changes in technology and fashion, social mobility, race relations and, my favourite, the ads!

The archive is bursting with over a century of iconic characters and stories, but there is so much more, and I look forward to seeing what else the custodians of the archive bring to us in the future.

Further Reading:

- Friardale.co.uk is an excellent resource on Story Papers, especially anything ‘Bunter’ related

- The Blakiana section of Mark Hodder’s site, mark-hodder.com, has everything you need to know about ‘Sexton Blake’

- ‘Judge Dredd’ writer Mike Carroll has great infographics on the various mergers of AP/IPC/Fleetway on his Rusty Staples blog

- ‘The Fun Factory of Farringdon Street’ by Alan Clarke is an excellent book on the history of AP

David McDonald is the publisher of Hibernia Comics and editor of Hibernia’s collections of classic British comics, titles include The Tower King, Doomlord, The Angry Planet and The Indestructible Man. He is also the author of the Comic Archive series exploring British comics through interviews and articles. Hibernia’s titles can be bought here www.comicsy.co.uk/hibernia. Follow him on Twitter @hiberniabooks and Facebook @HiberniaComics

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.