Third World War: The Future’s Arrived

13th February 2020

With Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra’s Third World War being reprinted in its entirety for the first time, the Treasury of British comics has commissioned short essays from selected comics critics that examine different aspects of this seminal political series from the pages of Crisis.

Tom Shapira’s first essay in the series can be read here. In the second essay, Kayleigh Hearn discusses how the series predicted, from the 1980s, how the rapacious nature of corporate America would use mascots, slogans, and branding to dehumanise and exploit…

“Forget science fiction, man. The future’s arrived: the greenhouse floods…identity cards…electronic tagging…police video cameras…you never know what the techno-pervs are going to dream up next.”

So says a member of Freeaid’s so-called peace force—a group of troubled, forcibly conscripted teenagers operating in South America—in Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra’s Third World War. Science fiction told us that in 2020 we’d have time travel and giant robots, so it’s a shock encountering a comic like this, originally serialized over thirty years ago, that isn’t just prescient, but exactly right. With its images of “forever wars” benefitting global corporations and sub-tropical forests burning to provide land for future Happy Meals, Third World War was a scalding prediction of late-stage capitalism. The future’s arrived.

Published between 1988 and 1991 in Crisis magazine, a spin-off of 2000 AD, Third World War is set in the then-future of, a-ha, 2000 AD. Among its accuracies is its depiction of young people at the dawn of the new century; its main character, Eve, wasn’t called a Millennial then, but she is one now. A politically conscious, black teenage girl growing up in the shadow of white, western paternalism, Eve is deemed “unemployable” by the country’s youth selection board and forced to join Freeaid. (As an example of the thin vein of dark humor that runs through the book, Eve knows she’s doomed when she tells the board that she’s studying art, English, and sociology.) “I’d always thought things would get better by 2000 A.D.” Eve confesses. “I hadn’t realized they’re getting worse. That it was so late…later than you think…”

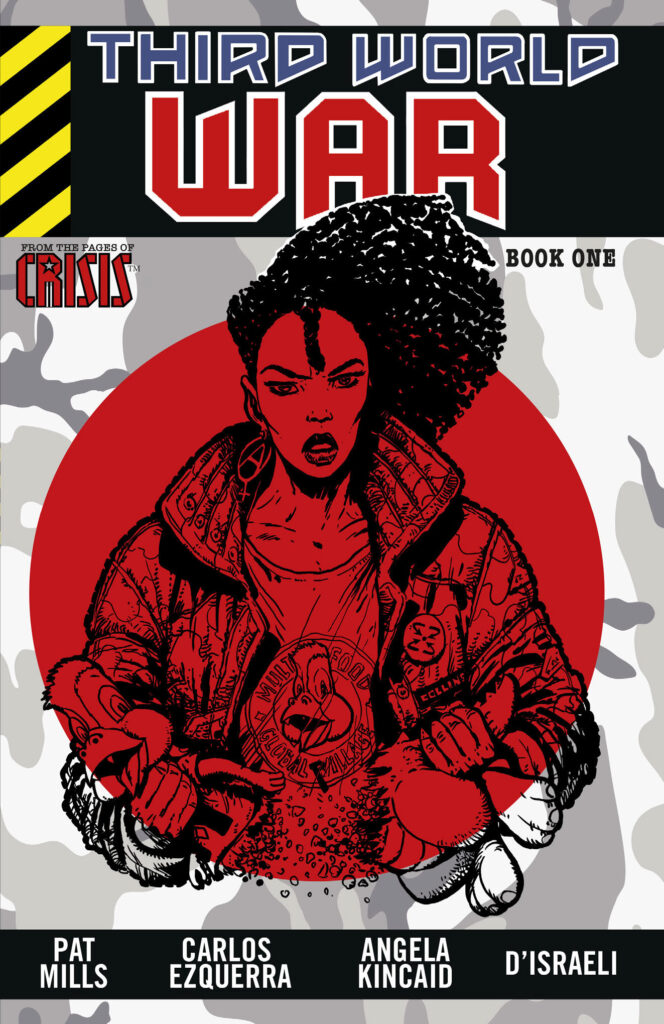

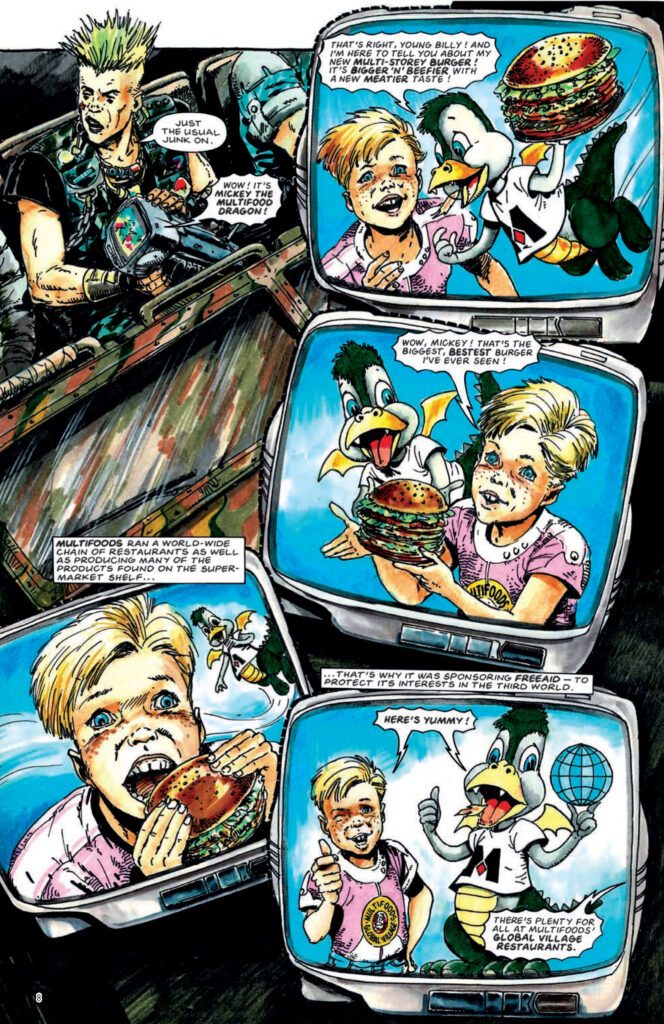

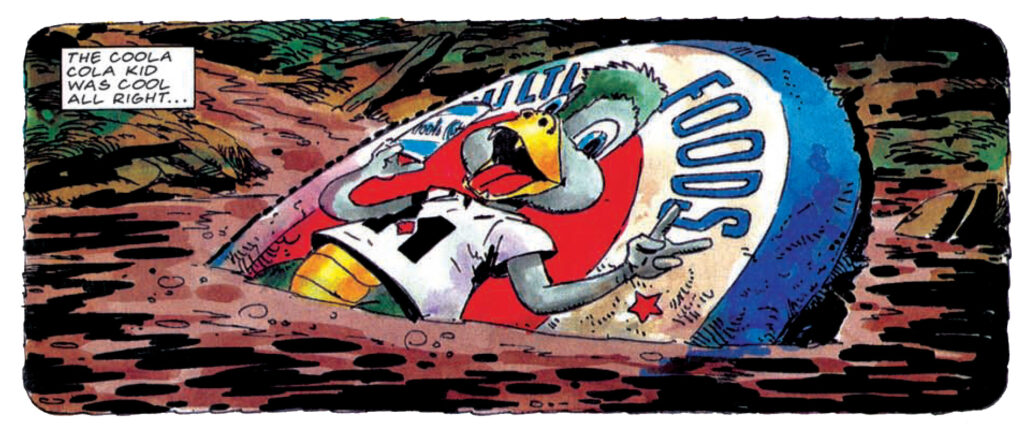

Eve and the rest of her Freeaid team—consisting of a punk, an eco-pagan, an evangelical, and worst of all, a volunteer—are sent to win over the hearts and minds of the South Americans who are being forcibly displaced and culturally annihilated for the sake of western corporations. One such corporation is Multifoods, a fast-food empire represented by its impish, ghoulish mascot, Mickey the Multifoods Dragon. A glance at the cover of this new Treasury of British Comics release of Third World War shows us a blood-red Eve ripping apart a Mickey plush toy, her Multifoods Global Village t-shirt fixed with a slash of a pen—Multifoods Global Pillage. Like the rest of her generation, Eve distrusts soulless mascots, empty slogans, and the back-breaking, environment-destroying corporations behind them. The headline writes itself: “Are Millennials Killing the Mickey the Multifoods Dragon Industry?”

Self-expression is one of the few weapons Eve has in a world that wants to bulldoze free-thinkers like her and replace them with pasty white faces in army fatigues. Like the P that transforms “village” into “pillage,” words of protest are scrawled all over the book, on every available surface: walls, planes, bodies. This is a distinct part of Third World War’s visual identity; Mills and Ezquerra (along with artists Angela Kinkaid and D’Israeli) synthesize the art and text—incorporating everything from Chumbawamba song lyrics to Lorraine Schneider posters into the pages. The unique reading experience that results is apparent from the very first page. Our eyes are first drawn to Eve and her internal monologue. But then we notice her “Meat is Murder” button and the “WHAT TO DO IF YOU’RE SELECTED” Freeaid poster completed by red graffiti: “PANIC.” Third World War is a book that demands to be read. It’s a manifesto, a polemic, and a protest sign, with layers of dense storytelling in a compact volume of two-hundred pages. Like a chicken bone caught in your throat, it’s impossible to ignore.

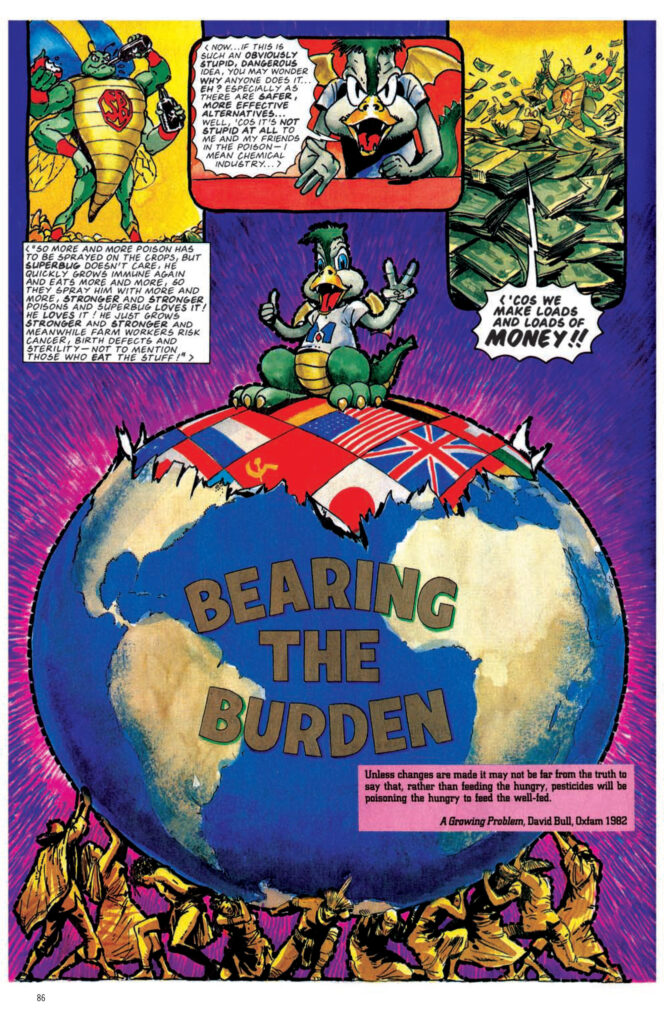

Third World War is an eye-opening book, as it shows death squads, mass graves, and other atrocities that are the bitter, pesticide-poisoned fruit of western imperialism, and dares the reader to look away. It’s an immensely heavy read, but its strength is that it never feels like a lecture; Mills and Ezquerra say what they need to through their characters instead of to them. Eve is a fallible, human lead, but she possesses a durable integrity and keeps a diary that is a document to everything that happens to her—the truth, not propaganda spewed from the mouth of a cartoon dragon. She isn’t in a platoon of strawmen, either; a lesser creative team would have reduced them to predictable stereotypes (Ivan the punk, Trisha the evangelical, etc.), but they’re shockingly believable in what they do and how they relate to each other. Think of them not as The Breakfast Club, but The Breakfast Sandwich Club, perhaps. Unfortunately, like so many other young people conscripted into meaningless wars, they’re grist for the Multifoods mill.

And, once again, we’re in the shadow of the dragon. Mickey the Multifoods Dragon is inescapable in Third World War, appearing on every tv screen (even the pirate channels!), peering at us over a folded page flap, or splitting a globe apart like juicy orange slices. It’s not a small detail that the Multifoods mascot is a beast known for its greed and rapacious appetite, or that he shares a name with the real world’s most monopolizing mascot. (And how fitting is it that the opponent of a fast-food dragon is named after the woman who first ate fruit from the Tree of Knowledge?) Ezquerra is a visual master, turning Mickey from cute to sinister with a flick of his pen.

If there’s one thing Third World War is missing—simply because Mills and Ezquerra aren’t oracles—it’s the internet; only Twitter could make that universe worse. But Mickey is a recognizable enemy in our current social media age where mascots and trademarks seem more alive than ever. Cartoony brands pretending to be just like you when they’re the smiling façades for corporations where the junk food they produce is the least of their sins? Mickey would love ‘em. Multifoods dehumanizes everyone it comes in contact with, from the vile lieutenant that seems to transform into Mickey while arguing with Eve, to Mrs. Garcia, a woman resettled by Freeaid who then commits suicide via immolation as protest, and becomes known only as “the hamburger lady.” In Third World War, meat is the message.

I hope I haven’t made Third World War sound too hopeless or cynical. That would be a disservice to its wit and depth, or its striking visuals (green-haired Ivan skateboarding in front of an inferno, firing his gun in the air, is just one image that sticks with me). It throbs with the kind of anger that’s usually accompanied by gamma radiation, but it’s a call to action rather than despair. With its depiction of endless war, blood-sucking corporate mascots, and a trapped generation of young people, Third World War creates a world recognizable as our own. The future’s arrived—time to do something about it.

Kayleigh Hearn is the Reviews Editor for Women Write About Comics, and has written for PanelxPanel, Shelfdust, and The MNT.

Third World War is available now in paperback from all good book and comic book stores, online retailers, and the Treasury of British Comics webshop in paperback and limited hardcover editions.

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.