Robot Archie is one of British comics’ most singular and loved characters. In his regular look at classic British comics and the Treasury archive, David McDonald explores the life and exploits of the world’s most powerful mechanical man…

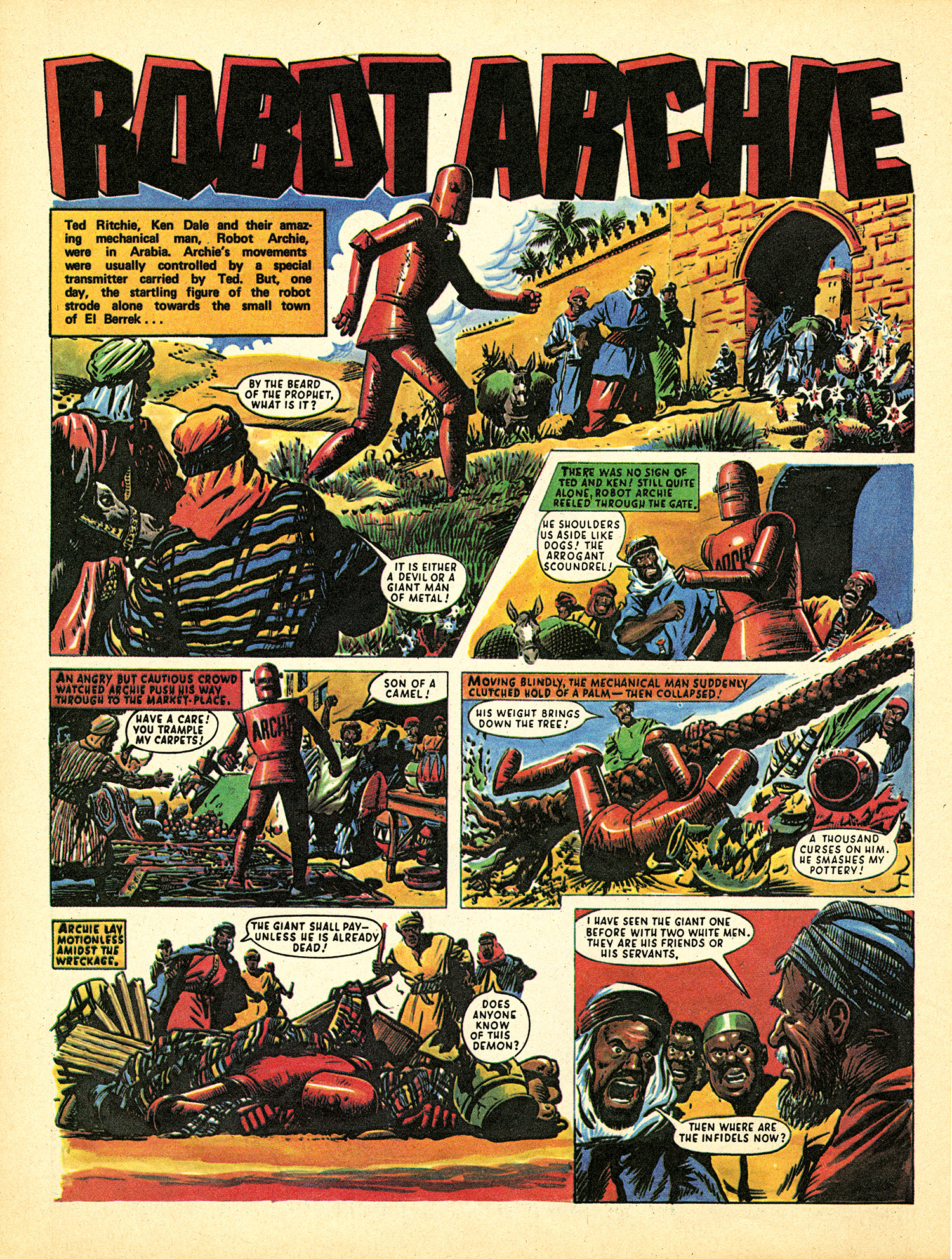

Content advisory: some of the images on this post contain offensive and outdated stereotypes, and are included for the purposes of historical interest.

What character has appeared in Lion, 2000 AD, in original adventures in America’s ‘DC’ Comics and in the Netherlands ‘Sjors’ comic too?

It’s none other than one of British comics most successful and well remembered characters, Robot Archie!

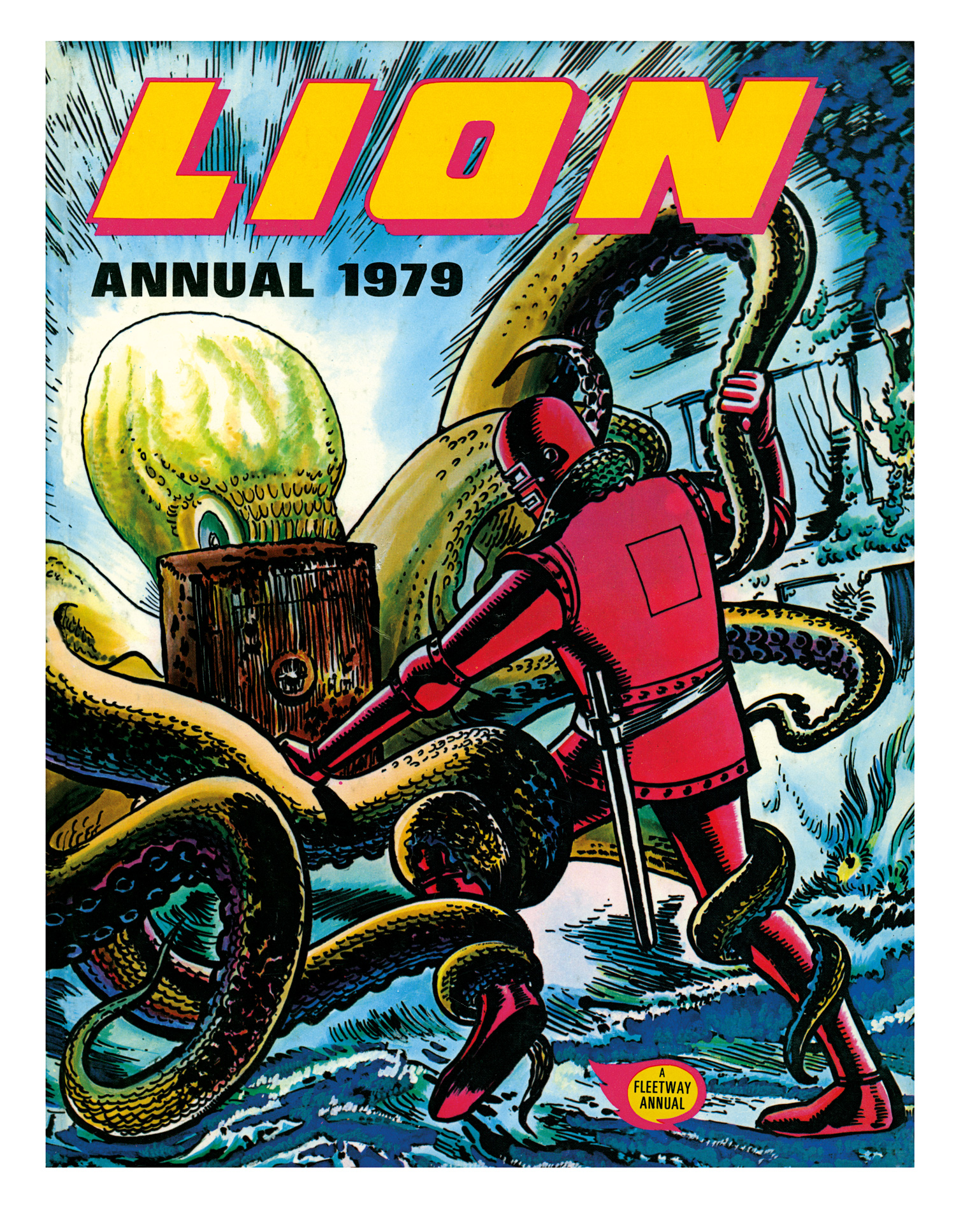

My first introduction to the character was in my older brother’s 1979 Lion annual. The cover with Archie battling a giant Octopus fascinated me, however, the accompanying text story inside disappointed me. I always felt a little short-changed with text stories in annuals, it was supposedly a comic!!

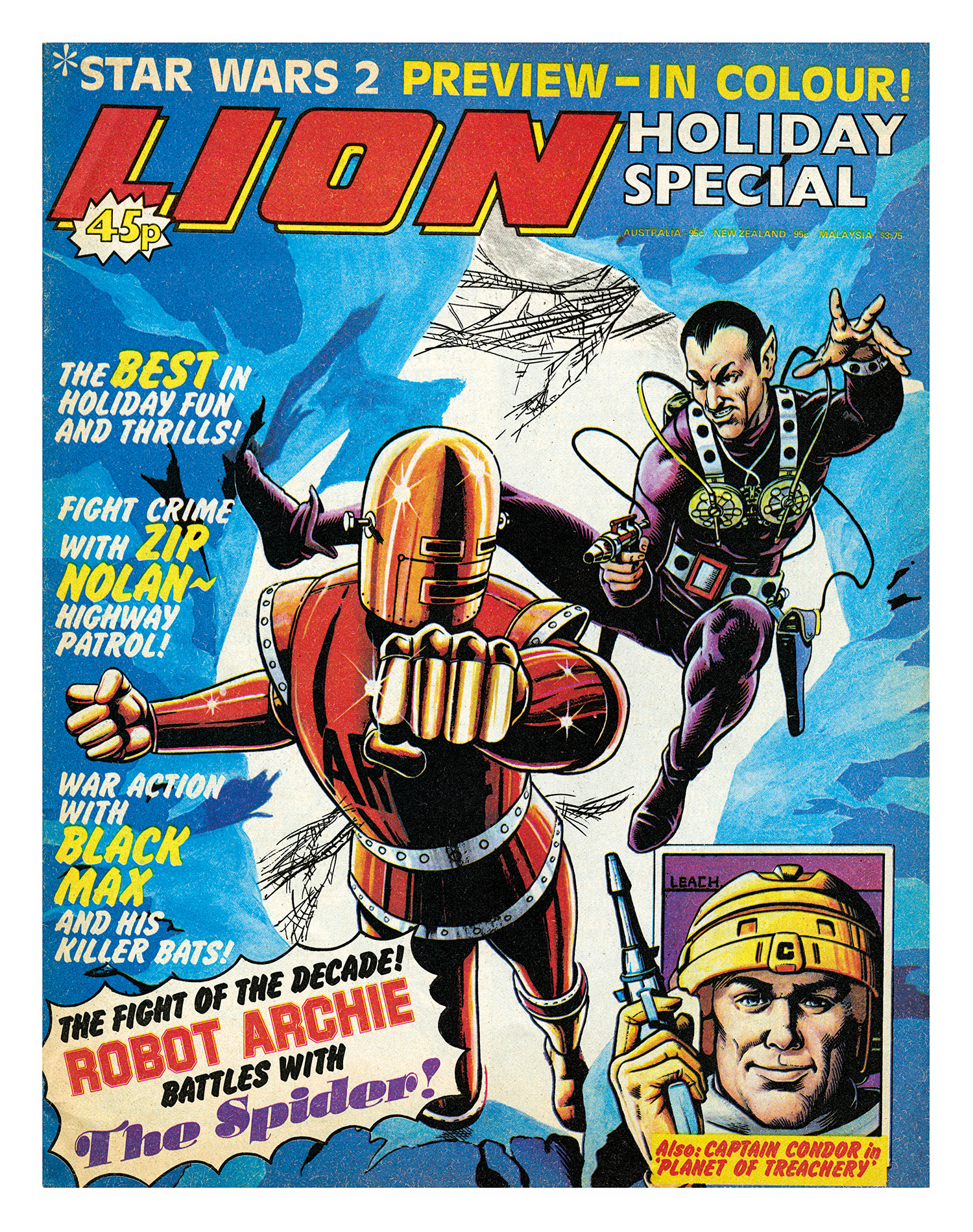

During the early eighties, Archie cropped up in various annuals and specials, including the 1980 Lion special with an amazing Garry Leach cover. That special was edited by Richard Burton- who would later edit 2000 AD. It’s well worth tracking down for the Archie v Spider story, which is probably the last new story featuring the characters for nearly a decade. It also has some Steve Dillon illustrations on the Captain Condor text story too which was possibly his first work for IPC.… but I digress, back to Archie!

From reading his adventures in the annuals and specials, I was hooked. A great character, sometimes in search of an equally great story. That great story landed in a surprising place in 2000 AD prog 627 in 1989. I’m getting ahead of myself a bit though, what of Archie’s origin and his ‘comic life’?

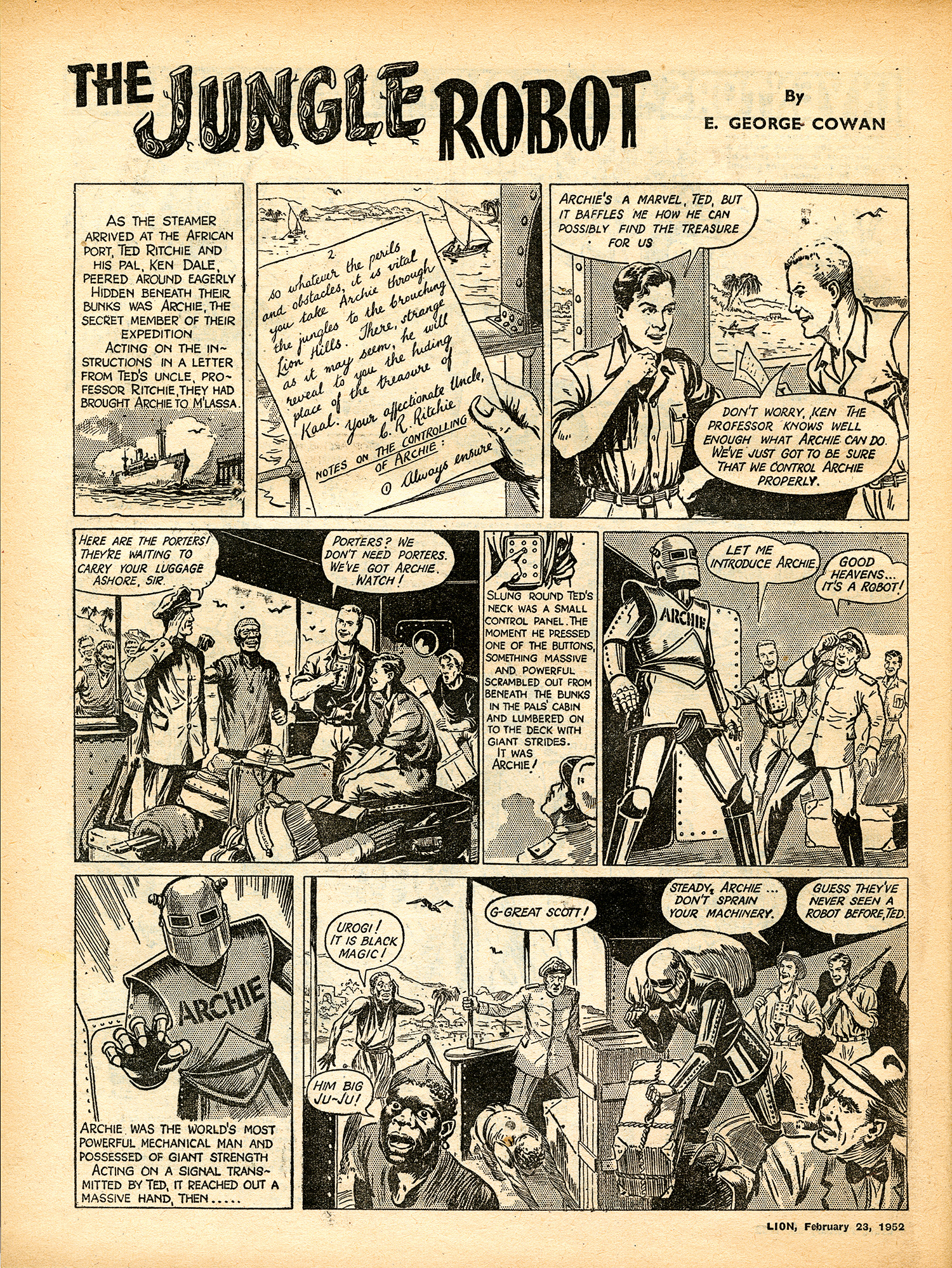

While Archie may have been one of Fleetways more popular characters, it took him a while to evolve into the swaggering and brash character that helped him become so well remembered. The character appeared in the first issue of Lion back in 1952 as the ‘Jungle Robot’ created by writer Ted Cowan and artist Alan Philpott. Archie, having been built by Professor CR Richie, was in the possession of the Professor’s nephew Ted Richie and his friend Ken Dale.

Archie was no more than a remote-controlled toy, operated by Ted Richie via a control pad he had in his possession. His first adventure only lasted six months, and it would be another five years before Archie returned to Lion in 1957, this time as Archie – The Robot Explorer. The new series continued much the same as the first tale, jungle adventures, on the trail of some lost treasure or villainous native. The next evolution in Archie was the addition of artist Ted Kearnon in 1958 who would become the character’s main artist until the end of the series.

Kearnon was an excellent draughtsman, who could draw literally anything the script threw at him. His depiction of Archie is the definitive one that we all now associate with the character.

Re-titled ‘Robot Archie’ in 1959, the final stage of Archie’s evolution happened in early 1966 when the Professor fitted him with a ‘mechanical brain’ and a voice box. Why this wasn’t thought of before is a mystery, but it was the final piece in the character, and with a masterstroke. Over the following year his personality emerged. He was brave, but also impulsive, vain, boastful and full of his own importance, which made for some great stories and interactions with his ‘owners’ Ken and Ted.

The post 1966 stories are the character’s golden age. The jungle settings were less frequent, and Archie had lengthy time travel adventures along with battling various monsters, both mechanical and traditional!

The addition of personality and a voice completely changed the stories from having Ken and Ted being in control of Archie and their adventures, to trailing behind Archie with his newfound bravado and overconfidence.

Archie continued in Lion until the title was cancelled in 1974. The seventies were tough on older comics. Lion and its stablemate Valiant were cancelled giving way to newer and brasher titles like Action and 2000AD. This wasn’t the end of the character though. In 1975 IPC in conjunction with Swiss publisher Gevacur published ‘Vulcan’ (titled Kobra in German). Vulcan was smaller than the traditional Fleetway size comic and reprinted some of Fleetway and IPC’s best-known characters. While the format and paper were quite flimsy, the printing was far superior than the newsprint that was used on most IPC comics. So stories like The Spider and The Steel Claw looked their best.

Archie appeared in Vulcan in full colour in what could be termed new material. It had been published previously, but in Dutch in the Netherlands! Archie was reprinted extensively in the sixties in the Netherlands, and when material from the UK ran out, Dutch artist Bert Bus produced new strips, some of it based on the original British material. It was these strips drawn by Bus that were reprinted in Vulcan, and while Vulcan only lasted 60 issues (the first thirty were only distributed in Scotland as a market test), the German language version Kobra lasted over 160 issues.

From 1976 onward, Archie was limited to his yearly outings in the Lion annuals and specials. He does make an early appearance in 2000 AD as one of Tharg’s droids in the story Tharg and the Intruder in Prog 24, drawn by Kevin O’Neill. His appearances finally came to an end in Lion Annual 1983, the last Lion annual.

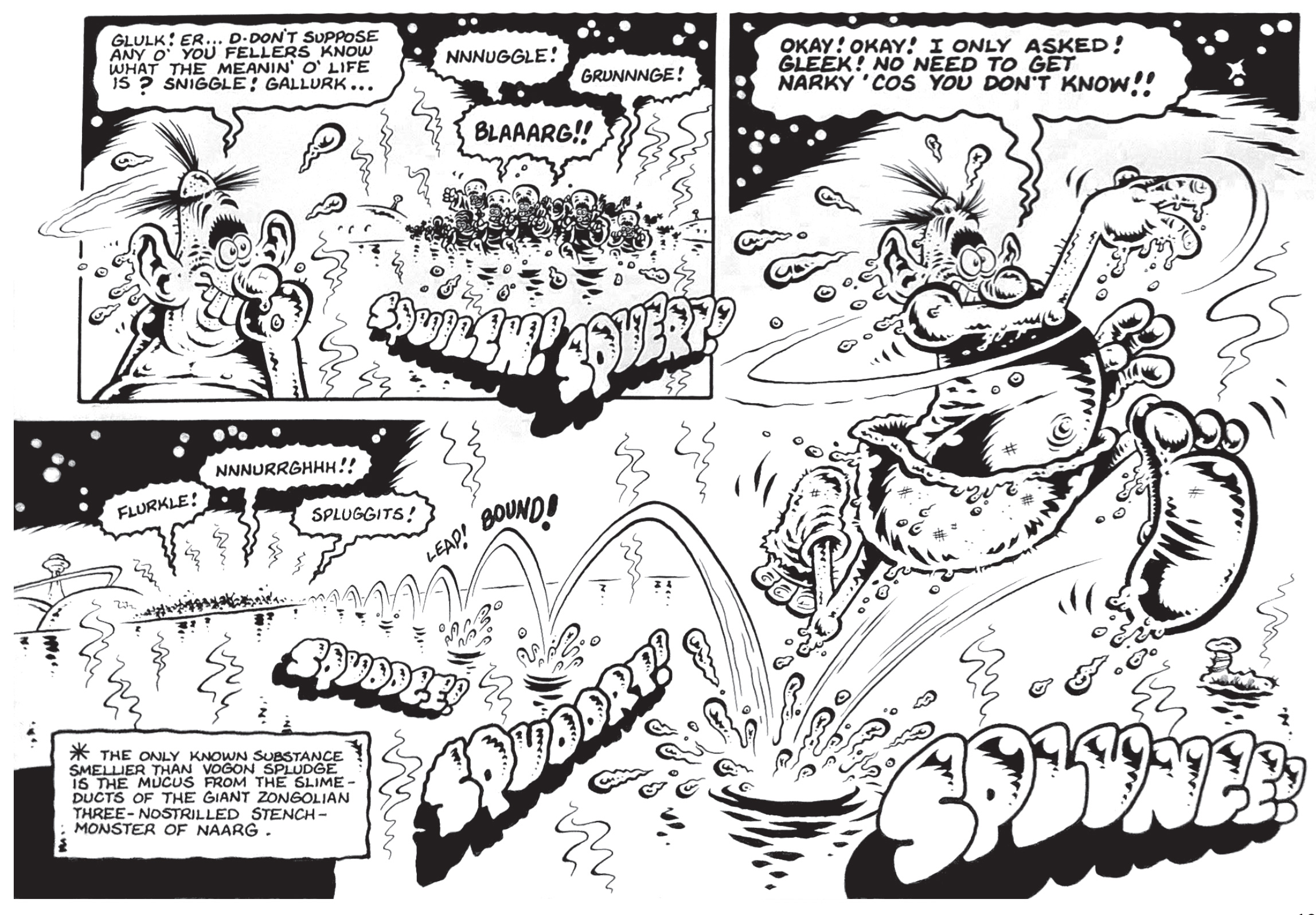

Back to 2000 AD Prog 627 in 1989, Archie crash-landed into one of 2000 AD‘s most popular series, Morrison and Yeowells Zenith! Zenith was a uniquely 2000 AD take on the superhero genre. Zenith was a spoilt selfish popstar, and a reluctant superhero. Archie appears in the third series of Zenith, and his transformation is so out there it works brilliantly. He is now a member of a supergroup, Black Flag, an aficionado of ‘Acid House’ music, self-styling himself as ‘Acid Archie’. His character essentially stayed the same as he appeared in the late sixties, and the new characteristics could be seen as an extrapolation of his personality growth in the sixties and seventies.

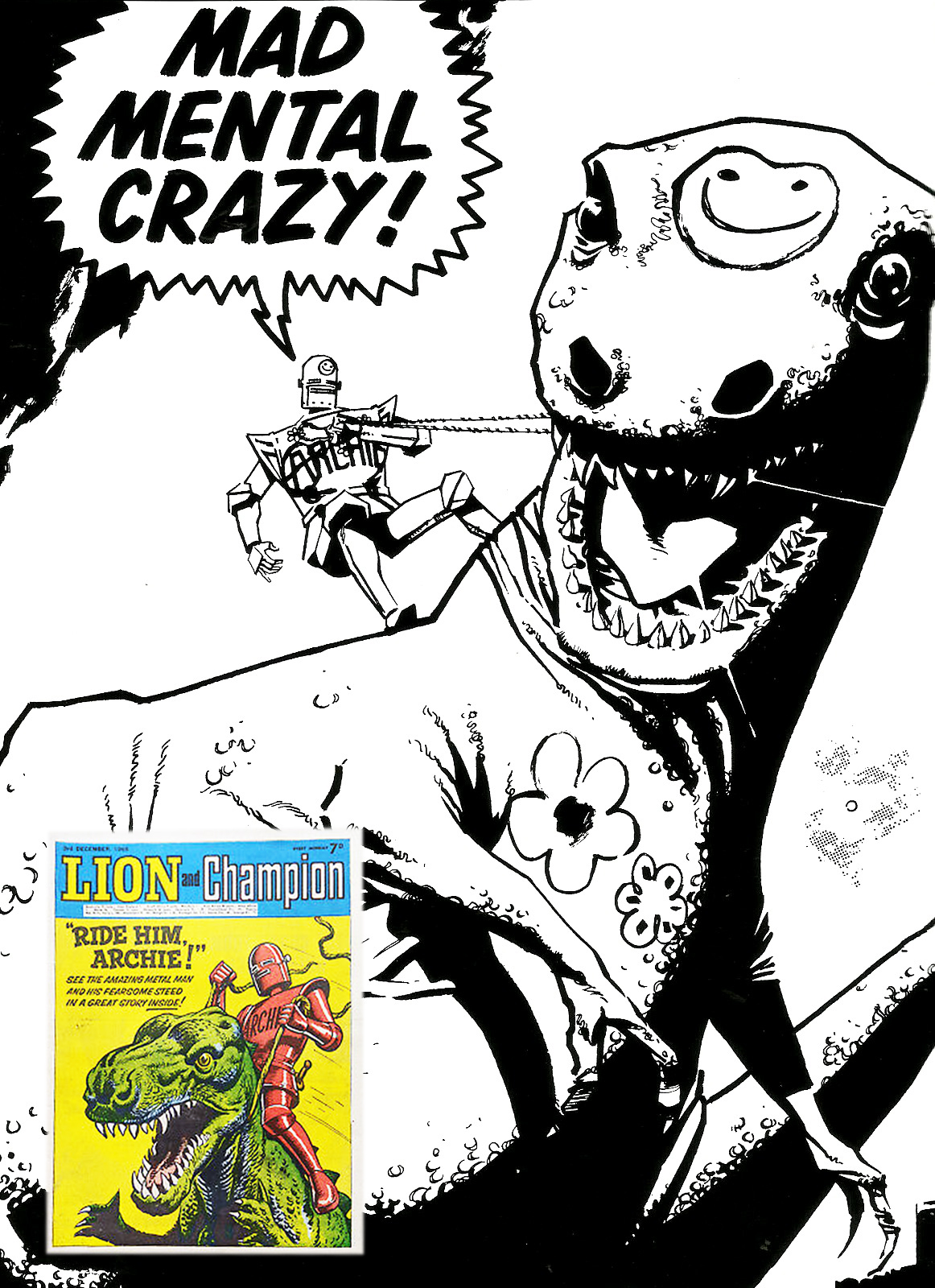

Archie played a central part in Zenith Phase Three and continued to crop up in later Zenith stories. One of his most memorable scenes is when he appears riding a flower adorned Tyrannosaurus Rex in Zenith! It was inspired by the cover of Lion (3rd December 1966) in the story Robot Archie and the Jungle Menace. A back cover poster of Archie that appeared in Prog 647 by Steve Yeowell raised my hopes that Archie was getting his own series in the Prog, but alas it never materialised.

During this time Archie also appeared in a new story in the Classic Action Holiday Special in 1990. This is a new story, but Archie is firmly in his 1960’s character, with some great art by Sandy James.

Due to the break-up of IPC’s comic assets in the mid-eighties into Fleetway and IPC Media, it turned out that when Archie was appearing in Zenith and the Action Special, Fleetway didn’t actually own the character! This break up in the mid-eighties meant that IPC Media owned Archie. Through various mergers and acquisitions, DC Comics in the US and IPC Media were part of the same company. Due to this association, DC published some of IPC Media’s assets in the US in the 00’s under the ‘Wildstorm‘ imprint. The titles they published were Battler Britton, Thunderbolt Jackson and Albion.

Albion was written by Alan Moore, Leah Moore and John Reppion, with art by Shane Oakley. It featured Archie on the front cover of issue one! Albion told the tale of how all of the various IPC, Fleetway and Odham’s characters had been incarcerated by the government in Cursitors Doom’s Castle and of Penny Dolmann’s efforts, with the help of a reconstructed Robot Archie to release them.

Since Albion, appearances of Archie have been few, although he continues in print in India. It’s also worth pointing out that Archie has inspired other Robots, Android Andy in Captain Britain and Tom Tom in Jack Staff are good examples. A broken-up Android Andy appeared in the first issue of Albion!

Rebellion’s acquisition of the old IPC/Fleetway comic assets now means Archie is back in the House of Tharg. He has been in comic wilderness now for a while, is it time for a return of Acid Archie?

C’mon Tharg you know it makes sense!

David McDonald is the publisher of Hibernia Comics and editor of Hibernia’s collections of classic British comics, titles include The Tower King, Doomlord, The Angry Planet and The Indestructible Man. He is also the author of the Comic Archive series exploring British comics through interviews and articles. Hibernia’s titles can be bought here www.comicsy.co.uk/hibernia. Follow him on Twitter @hiberniabooks and Facebook @HiberniaComics

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.