An Annual under the tree was a Christmas tradition for generations of kids. In his regular look at classic British comics and the Treasury archive, David McDonald takes a look at the once booming publishing phenomenon…

Annuals are a publishing phenomenon stretching back well over a century. The term ‘Annual’ in publishing covers a lot of different types of books, – almanacs, yearbook and Annual reports, but the ones this piece is concerned with are those titles that one would associate with comic and story papers, traditionally given at Christmas.

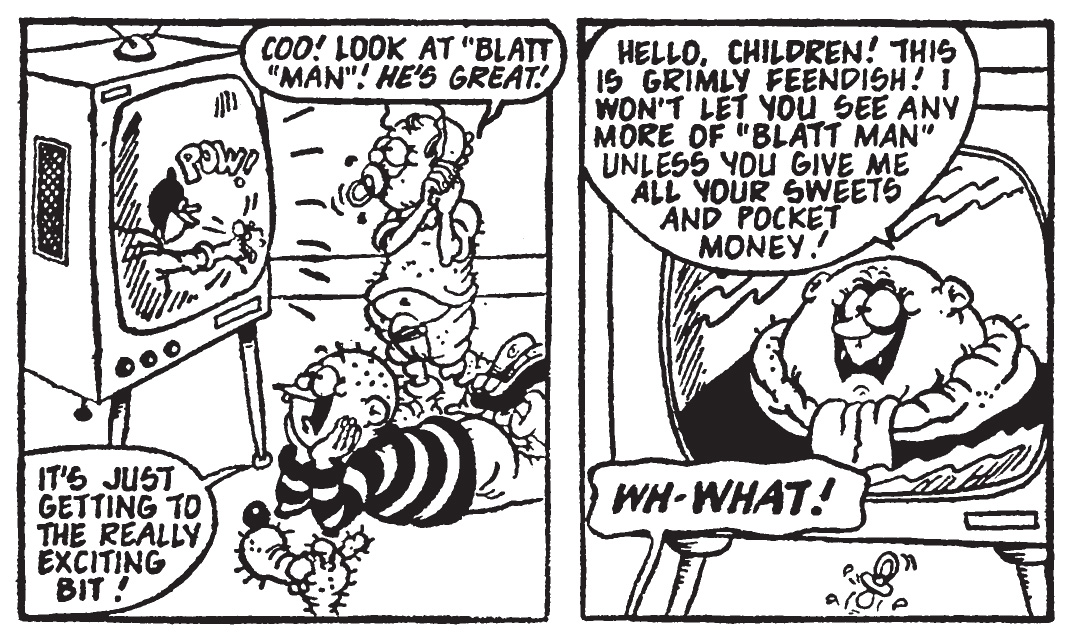

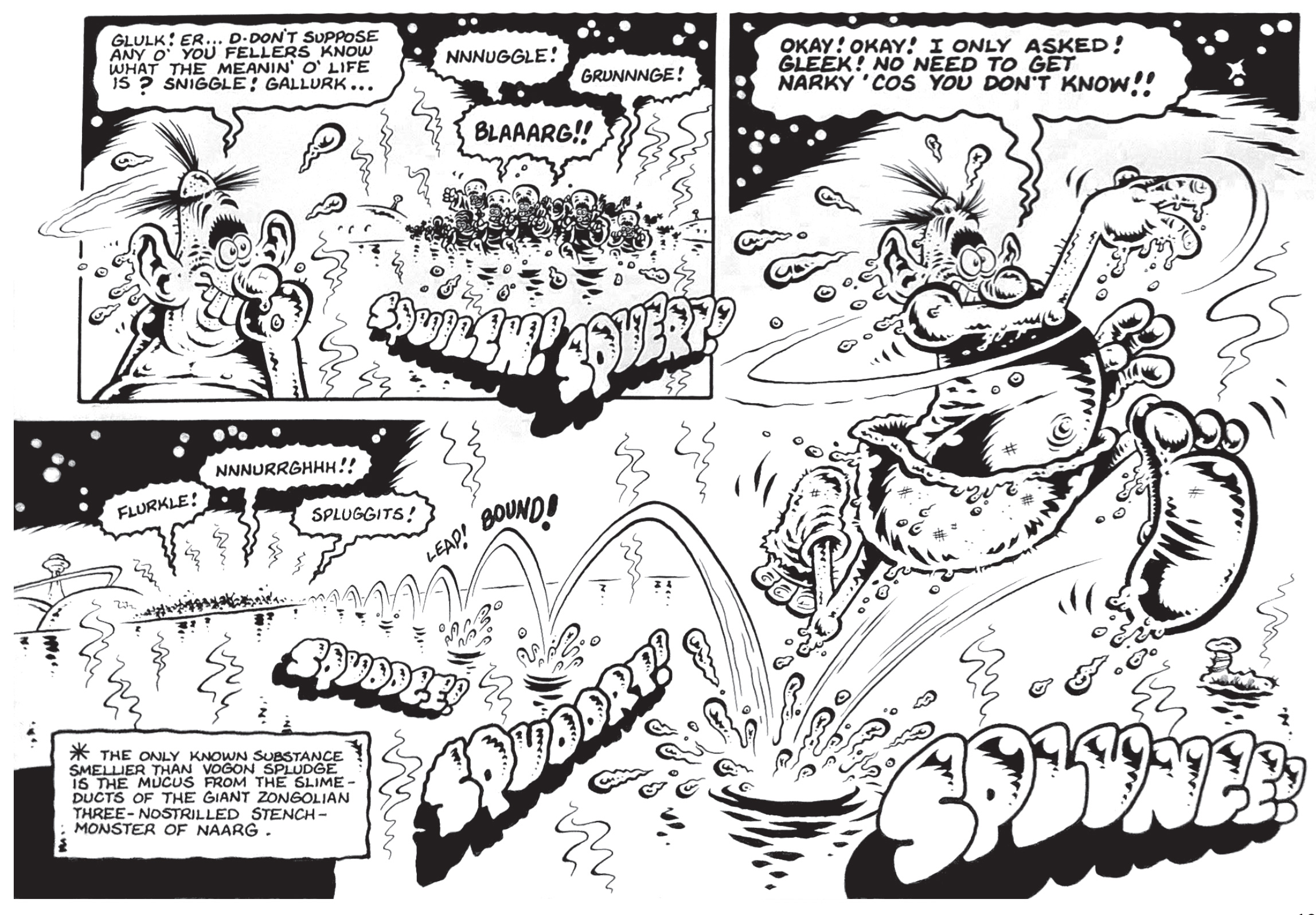

The seventies and eighties were the golden age of Annuals. They were ubiquitous at Christmas, with an Annual on most kids’ Santa list, and for those that did not ask for one they could be sure a grandparent or relative would bring them as gifts.

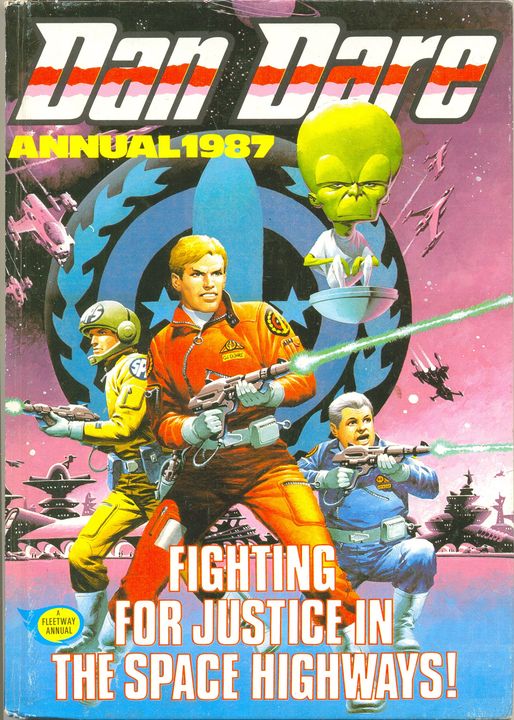

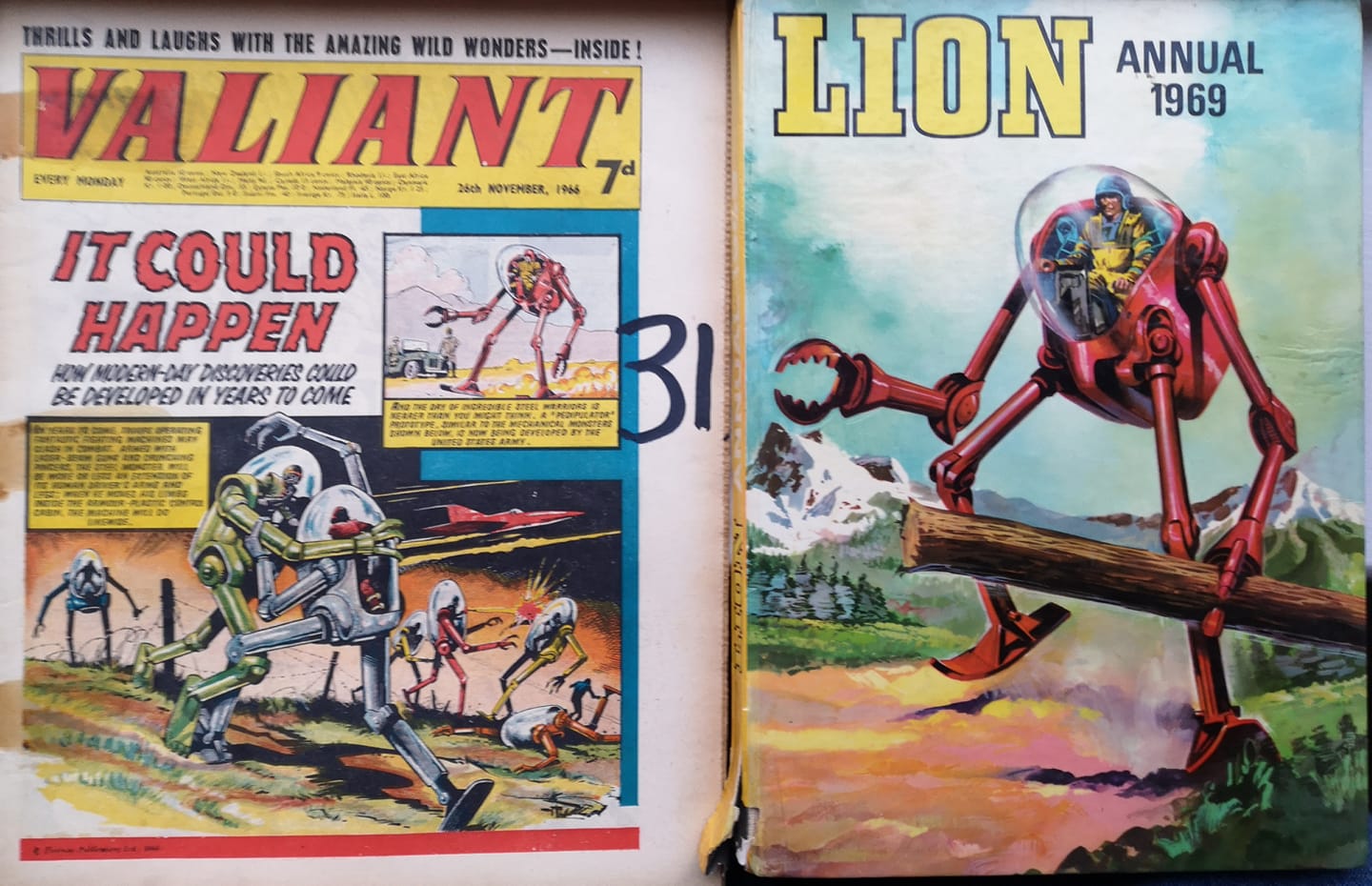

Annuals would go on sale late summer or early autumn, dated the following year, e.g., Lion Annual 1973 would have gone on sale in early autumn 1972. Firmly geared to be a Christmas buy, they were heavily promoted in the weekly comics and in newsagents and toy shops too. Posters and flyers would be sent to proclaim on the shop windows that Annuals were now in stock. Once Christmas was over, whatever Annuals were left in stock were out of date and would be heavily discounted and sold.

Some Annuals do turn up on occasion with no year printed on the cover. It’s possible that these were published without a date for overseas markets, like South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, giving the titles extra shelf life in case of any shipping delays.

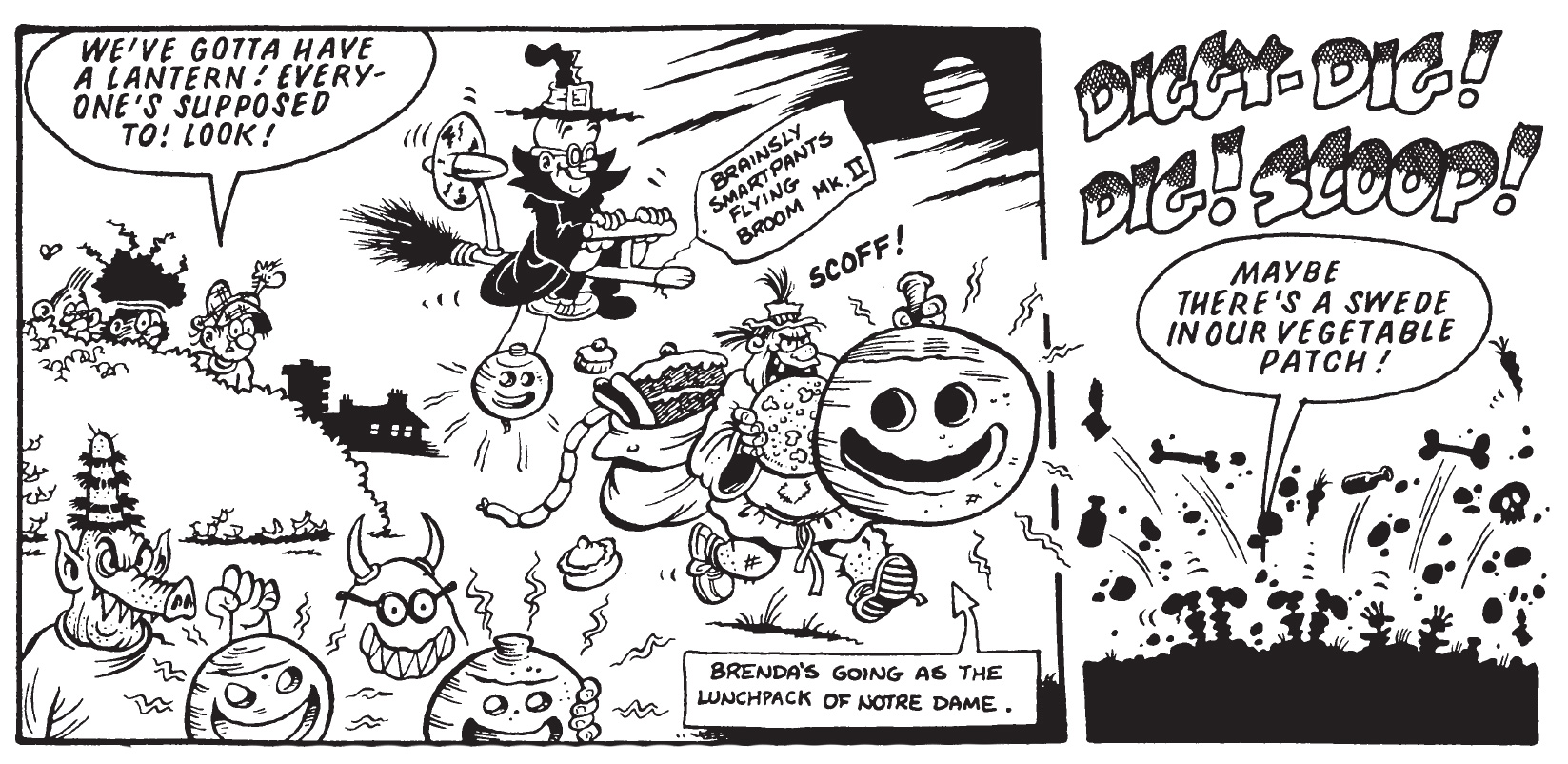

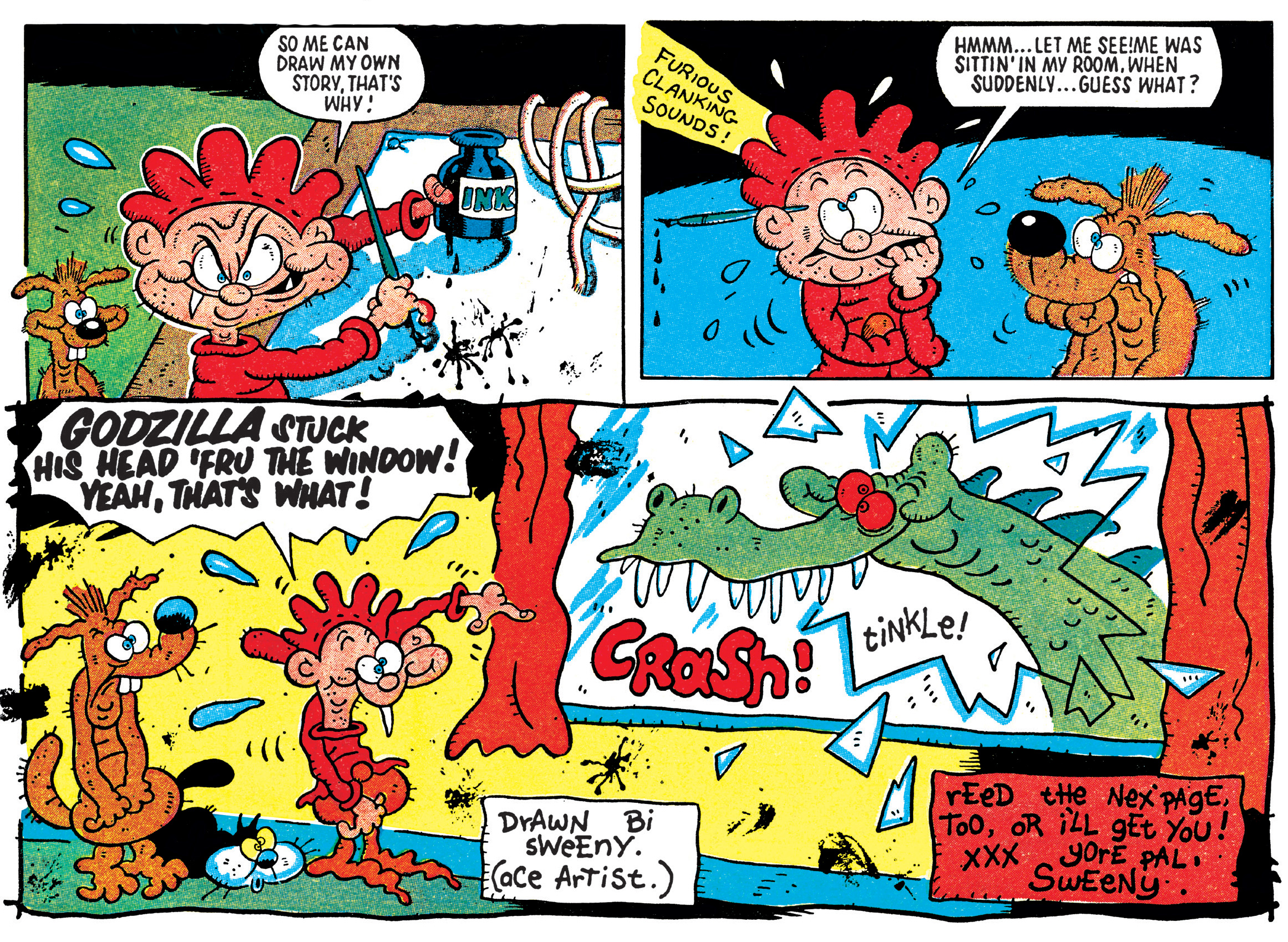

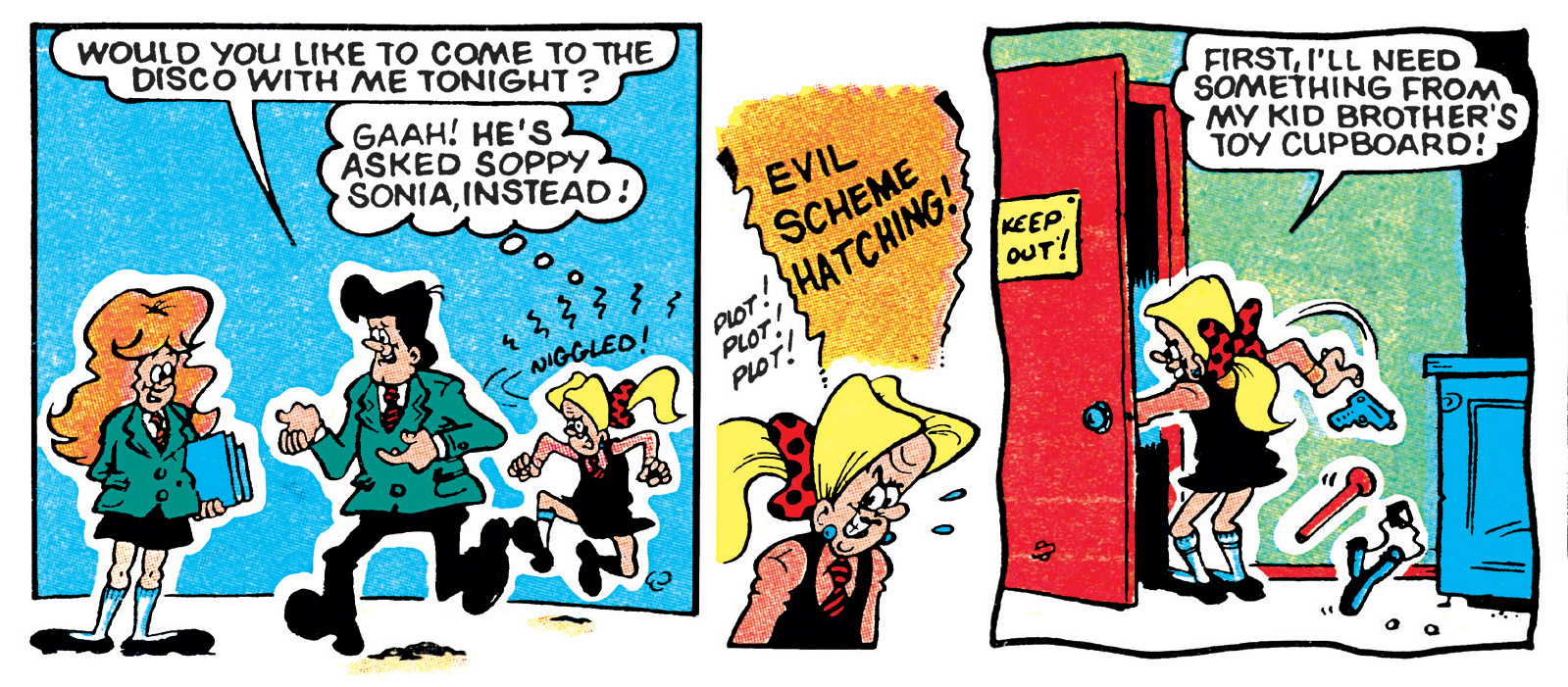

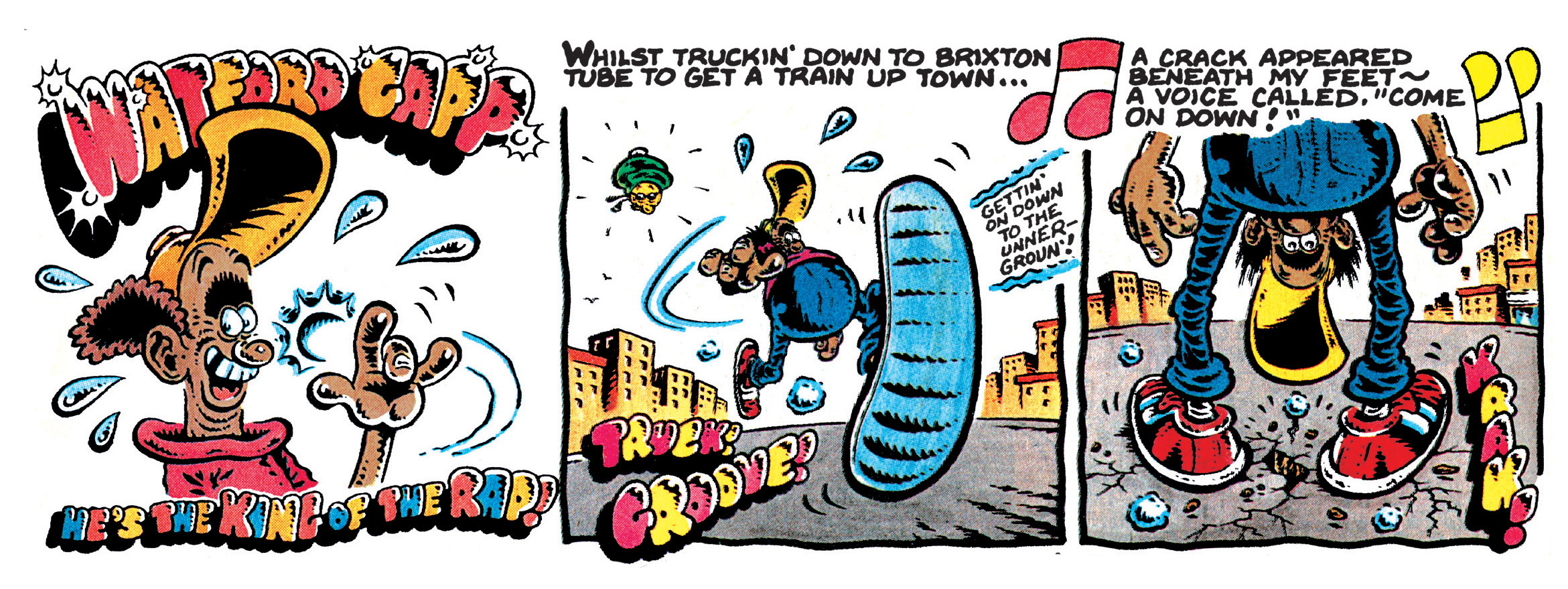

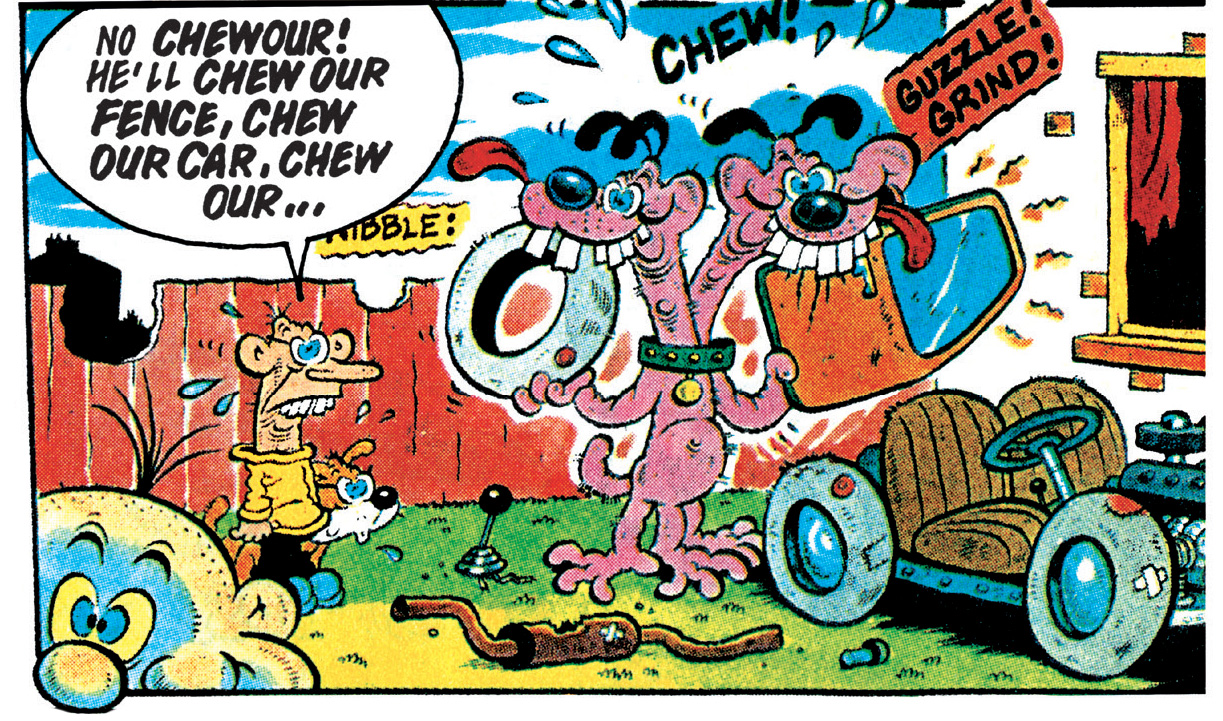

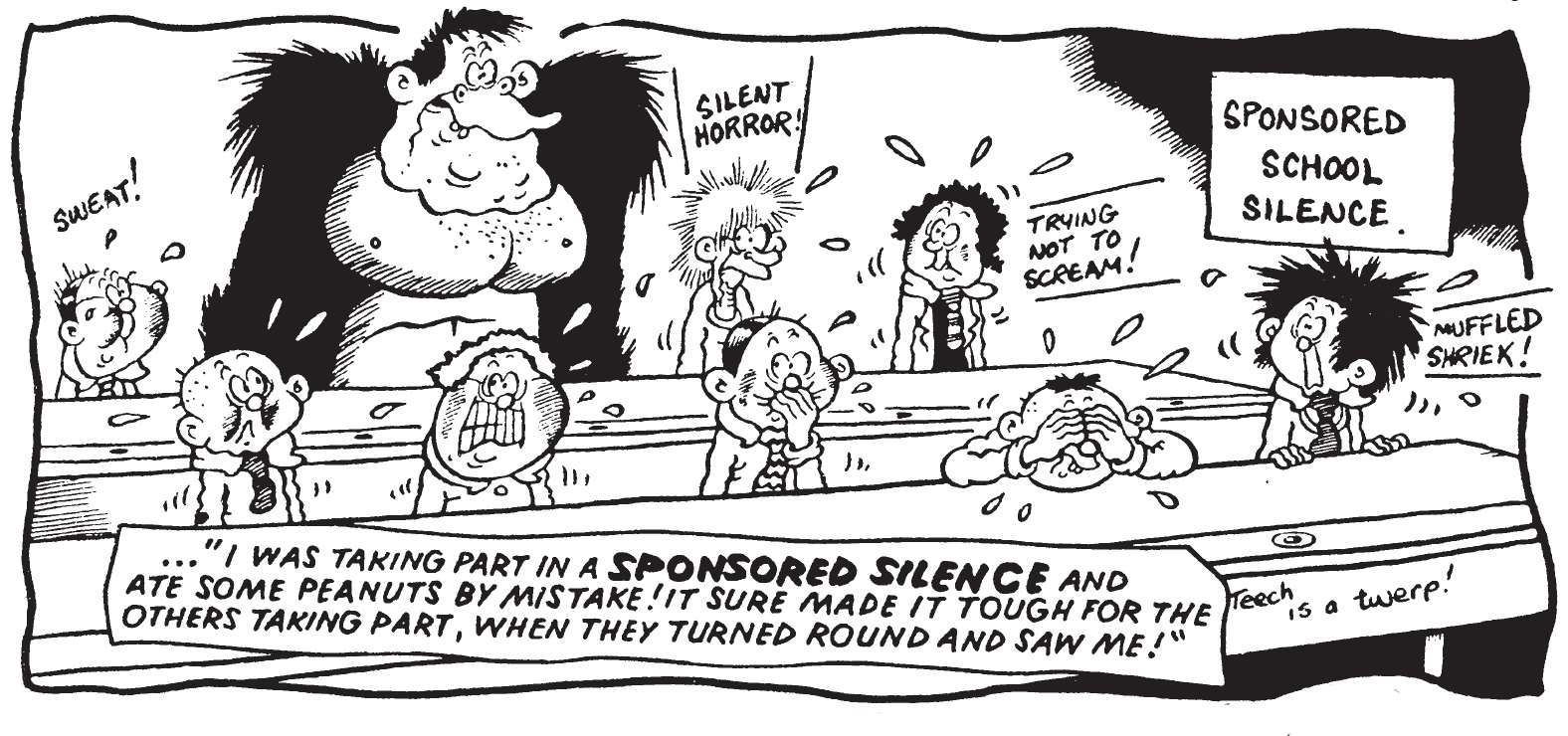

The format of the Annuals was generally uniform, hardback and A4. Colour was sporadic and depended on the publishers, some having a full colour section with the rest all black and white. Some had spot colour throughout of blue or green and some were even full colour.

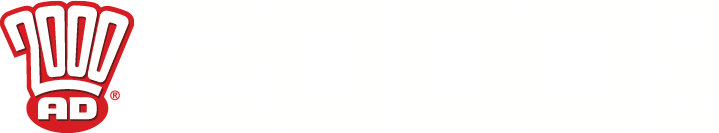

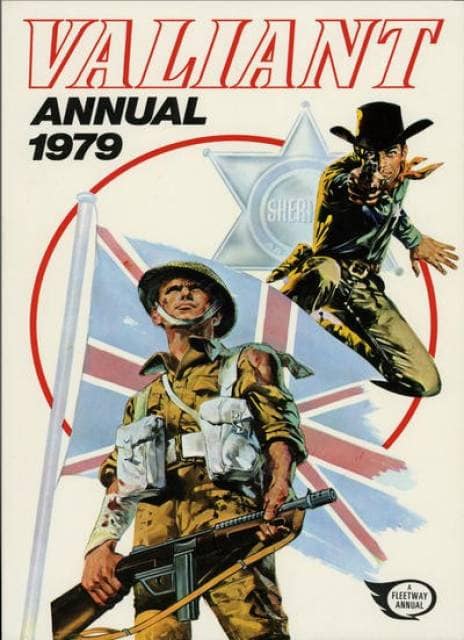

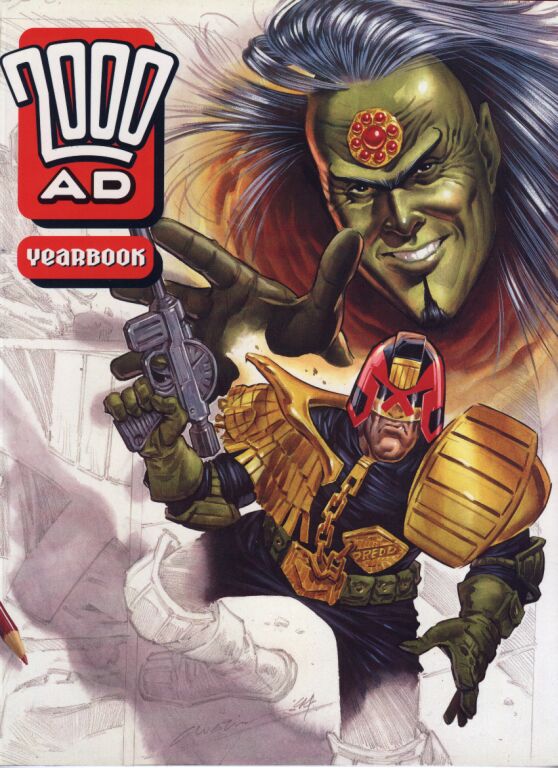

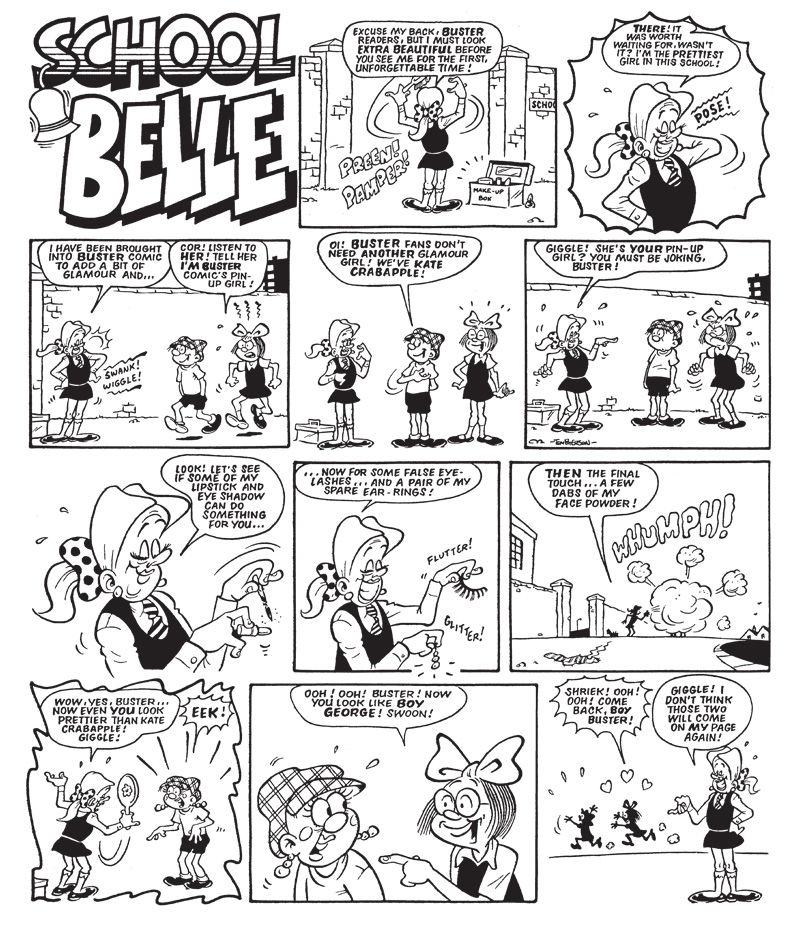

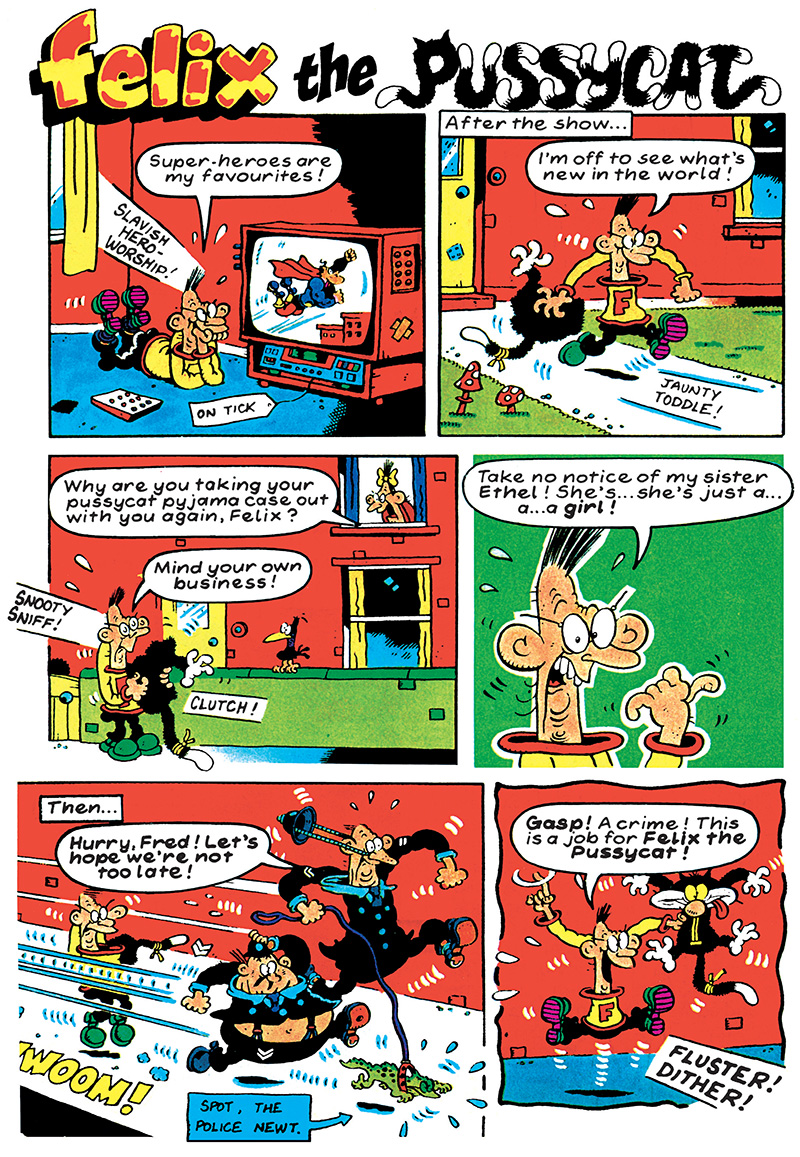

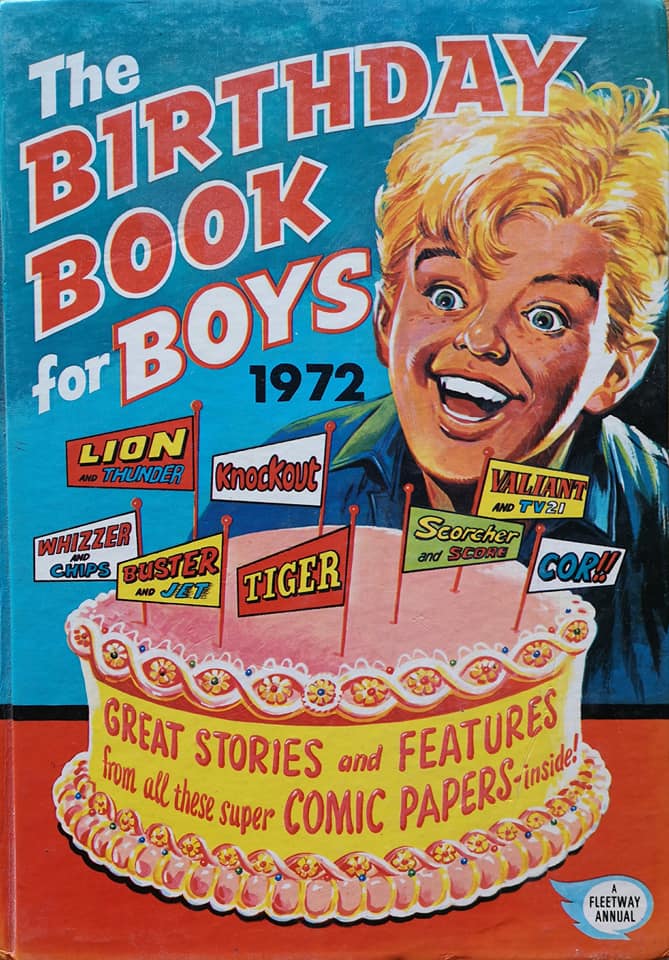

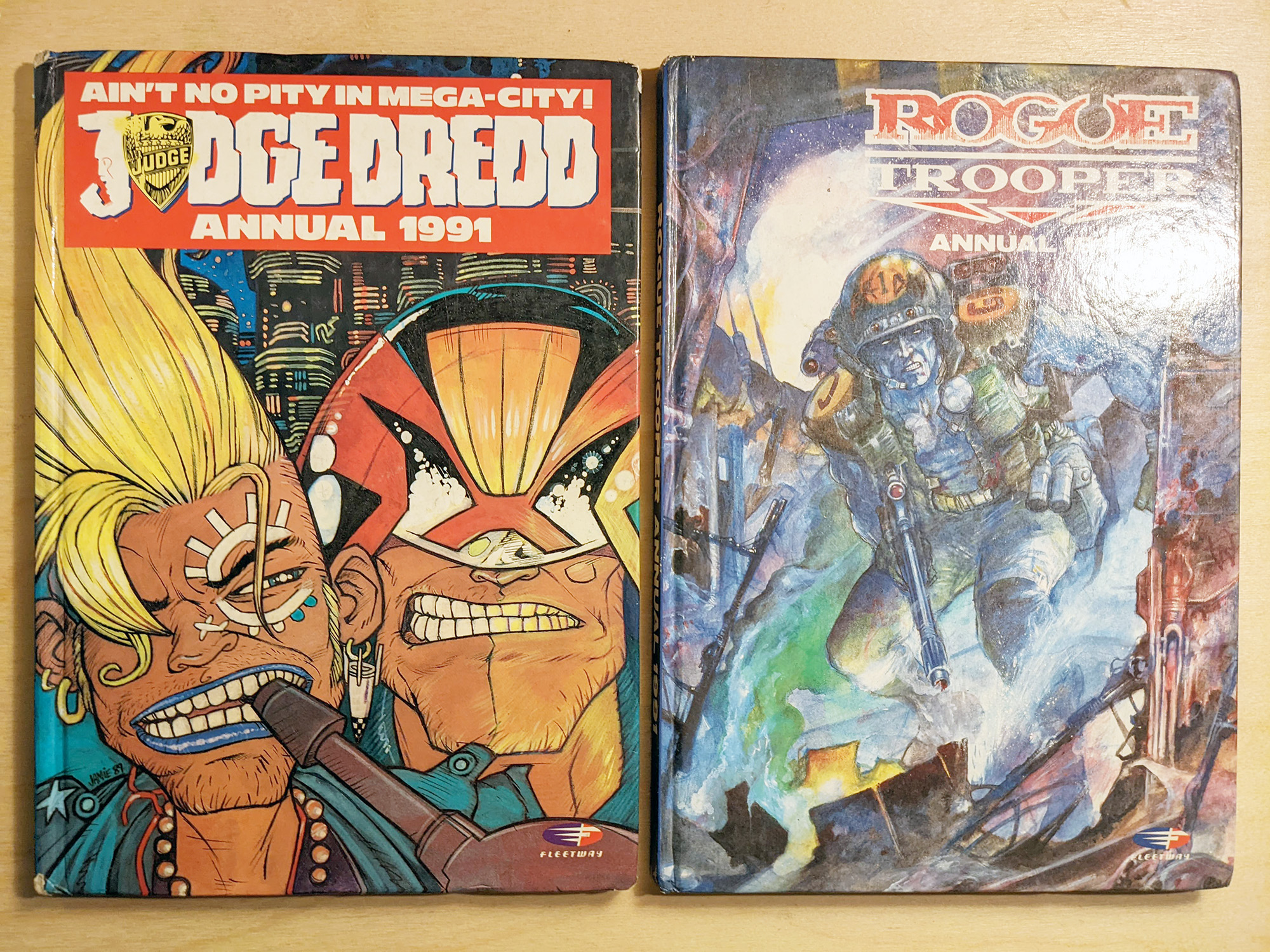

Occasionally different formats were used, like softback or editions like ‘Summer Annuals’ and ‘Birthday Books’. Some titles would have spin-off Annuals from the main title. Buster had several joke book titles – ‘The Buster Book of Gags’, Valiant and Lion had ‘sport’ and ‘war’ titles, Tiger had Roy of the Rovers Annuals and 2000 AD had Dan Dare, Judge Dredd and Rogue Trooper Annuals.

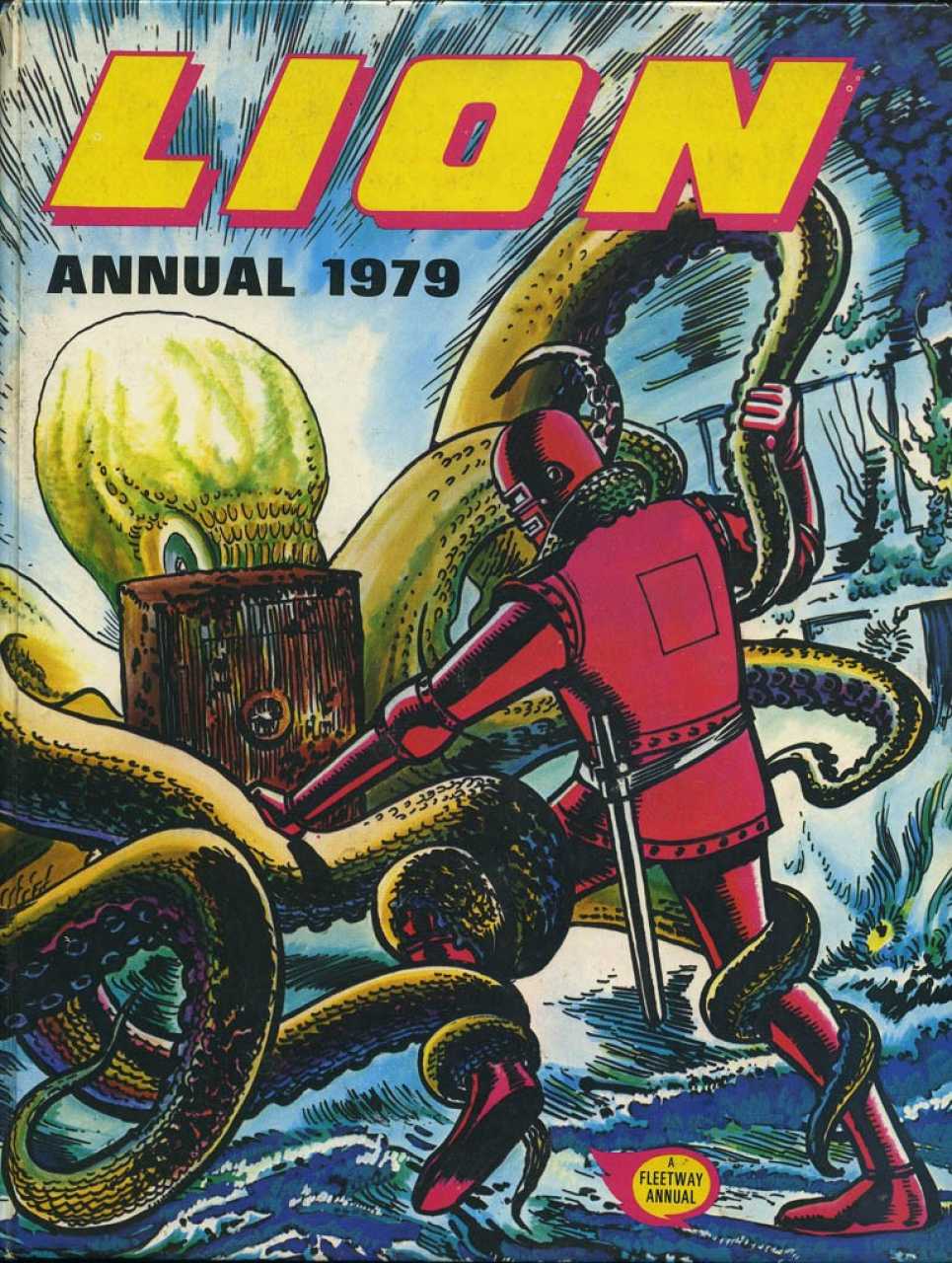

The range of titles available was staggering. In 1980, (cover dated 1981) for example, there were 10 publishers in the UK producing over 200 titles! A lot of the titles that were published were licensed spin-offs of television programmes or sports personalities. They had little or no comic content and had no supporting weekly or monthly. Some like Star Trek and Marvel titles did have comic content but in general they were reprints of American material.

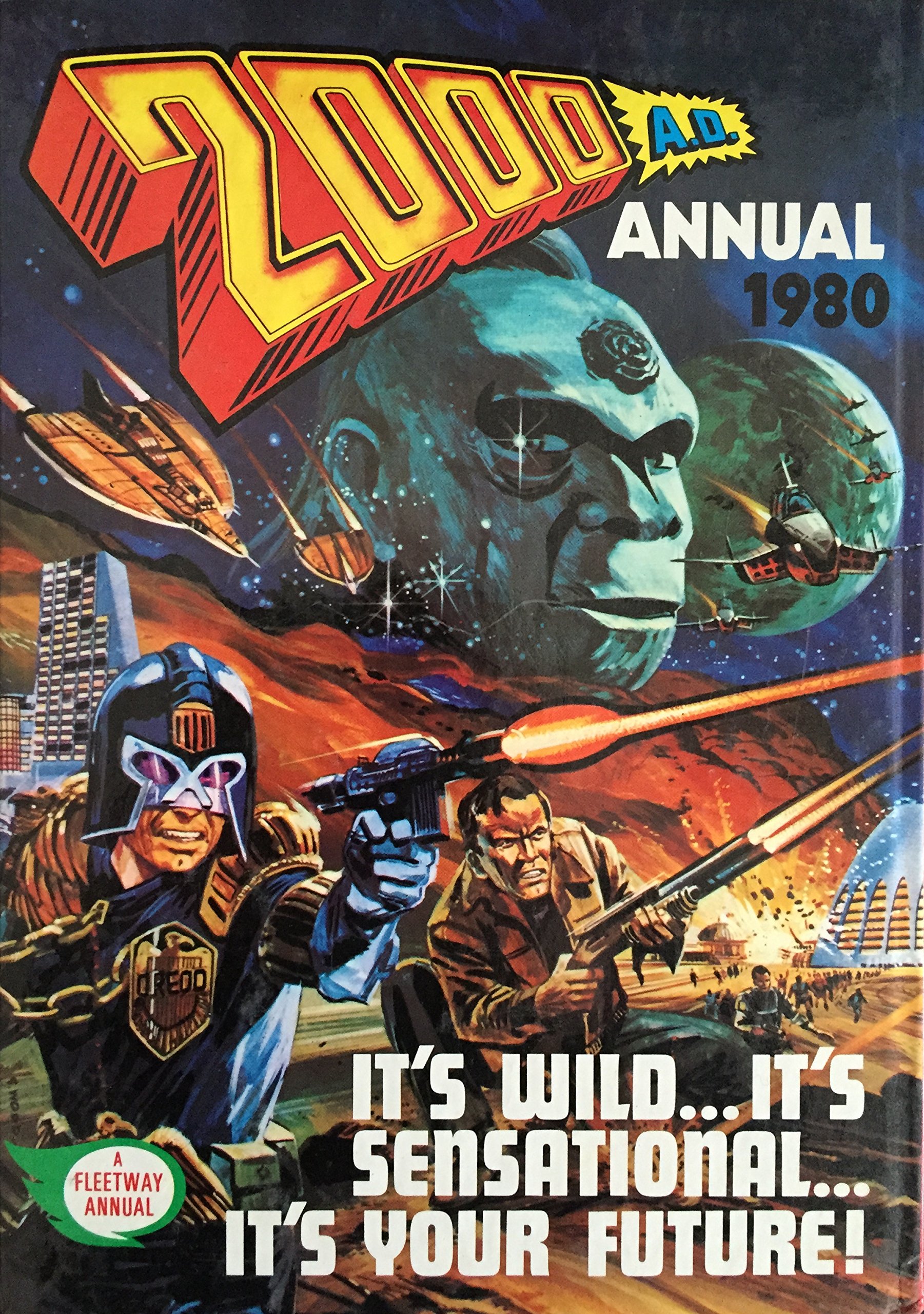

By far the biggest publisher of Annuals in 1980 was IPC magazines. It published a whopping 60 Annuals under the ‘A Fleetway Annual’ brand which was instantly recognisable. The winged ‘speech bubble’ logo with ‘A Fleetway Annual’ in bold adorned the front cover of every Annual. Introduced in 1973, the design was an adaptation of the old Fleetway Library logo. It was an effort to create a unified and recognisable brand of all the disparate parts that made up IPC’s juvenile department.

Annuals were big business for Fleetway, they sold in large quantities and were cheap to produce. All of IPC’s juvenile department got Annuals. Preschool titles, girls and boy’s comics and the teen photo strip magazines all had Annuals, as did some of IPC’s magazine titles like the Anglers Mail and Shoot!

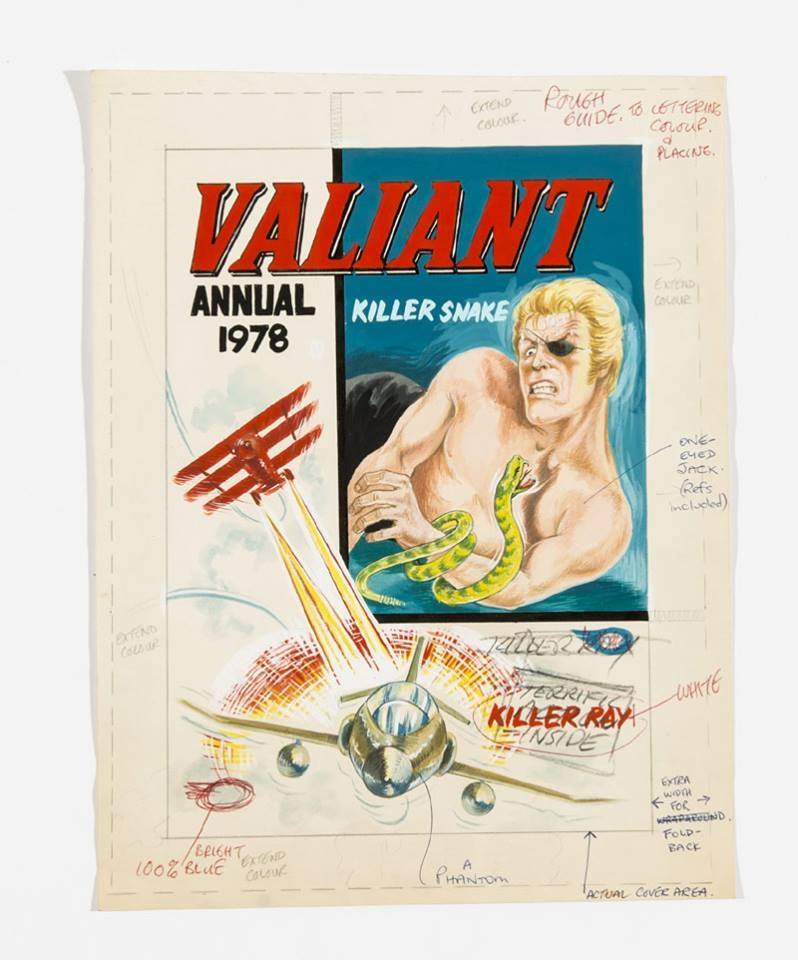

In general, they consisted mainly of reprint with a small budget for a section of newer material. For long running titles like Valiant its editorial team had an extensive back catalogue to use. The Annuals could be stuffed with reprints, put on a new cover with a small amount of newly commissioned pages and you have an attractive package.

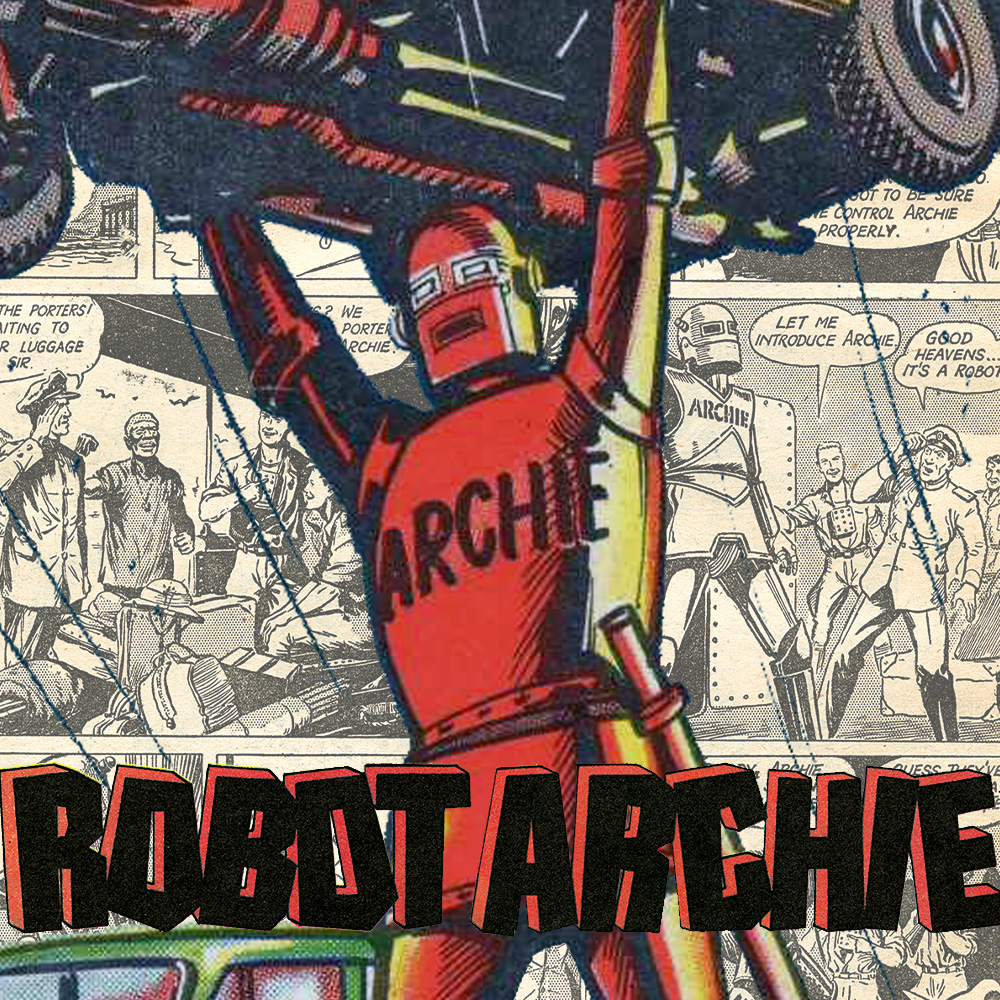

When a new title was launched it didn’t have the back catalogue of reprint to use, so similar material from older titles was used. For example, when the first few 2000 AD Annuals were published, they reprinted The Guinea Pig, UFO Agents and The Phantom Patrol from the Eagle and Swift.

A ‘live’ weekly Annual would be produced by the editorial team of that title in a freelance capacity. So, for example, Battle Annual 1979 would have been produced by Battle editor David Hunt and his team.

Producing an Annual on top of the ongoing rush to get the weekly to the printers was often difficult. Annuals were also an opportunity to blood new creators or use up material that may have been commissioned and not used in weekly titles for whatever reason.

Annuals of live titles usually had new covers and new stories of the current stars of the comic, some in colour as well as reprint of older material.

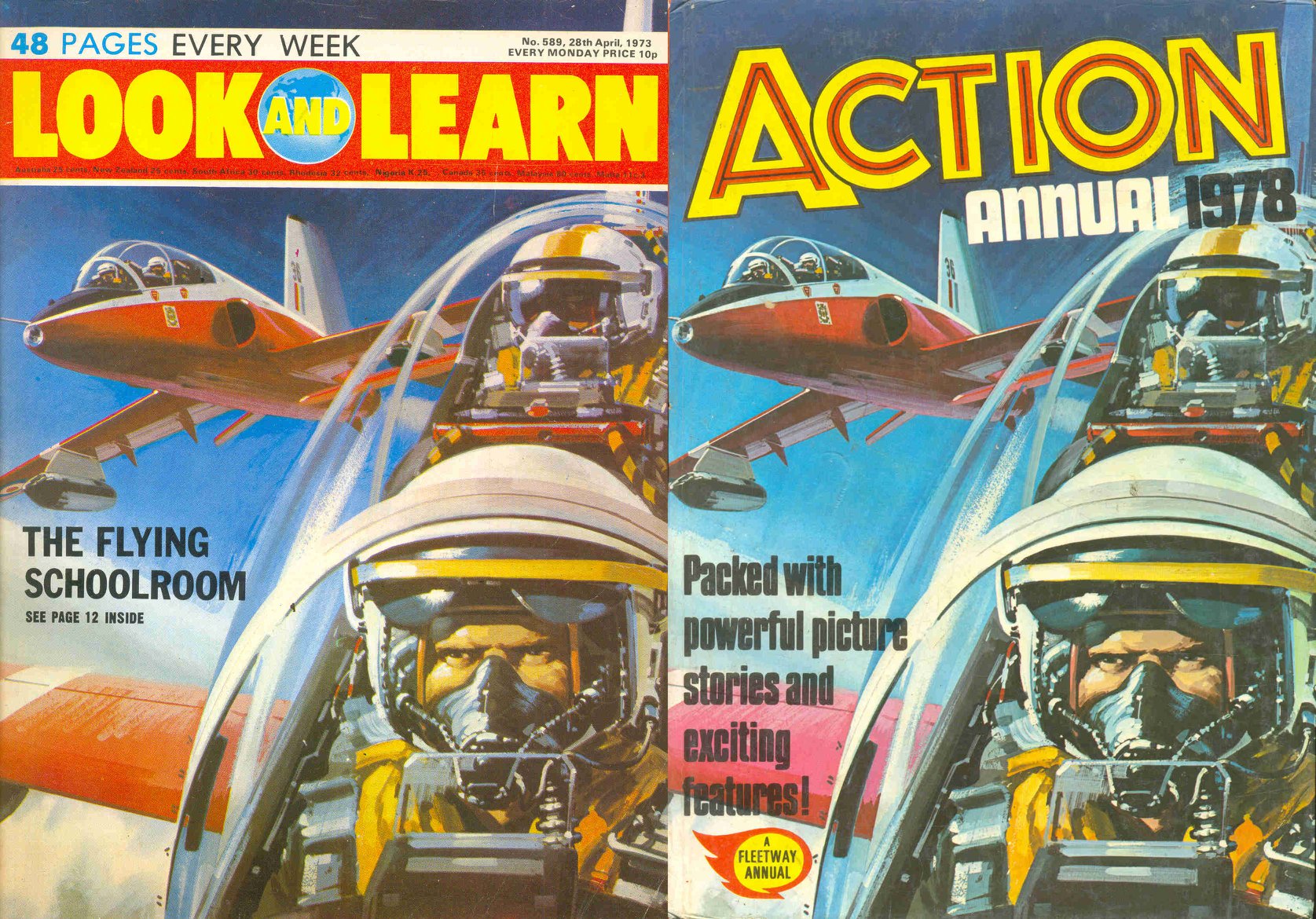

The Annuals of ‘dead’ titles i.e., an Annual of a weekly that had been cancelled, sometime years beforehand, were produced in the IPC offices freelance by whatever editorial staff members were available. Often nearly completely reprint, even the covers would be reprinted from older picture libraries or Look and Learn. Features would be used a lot for content compared to the Annuals of live titles. The format the Annuals used was slightly different to the older comics meaning that reprinted comic artwork would have to be altered. There would not have been the budget or personnel to reformat enough comic pages, so features, often pulled from educational titles like Look and Learn or World of Wonder, were quick and easy fillers. Annuals of dead titles often ran for years after the weekly titles’ demise. Knockout weekly ended in 1973, but it’s Annuals continued until 1985 (pub. 1984), a full 11 years after the title’s cancellation!

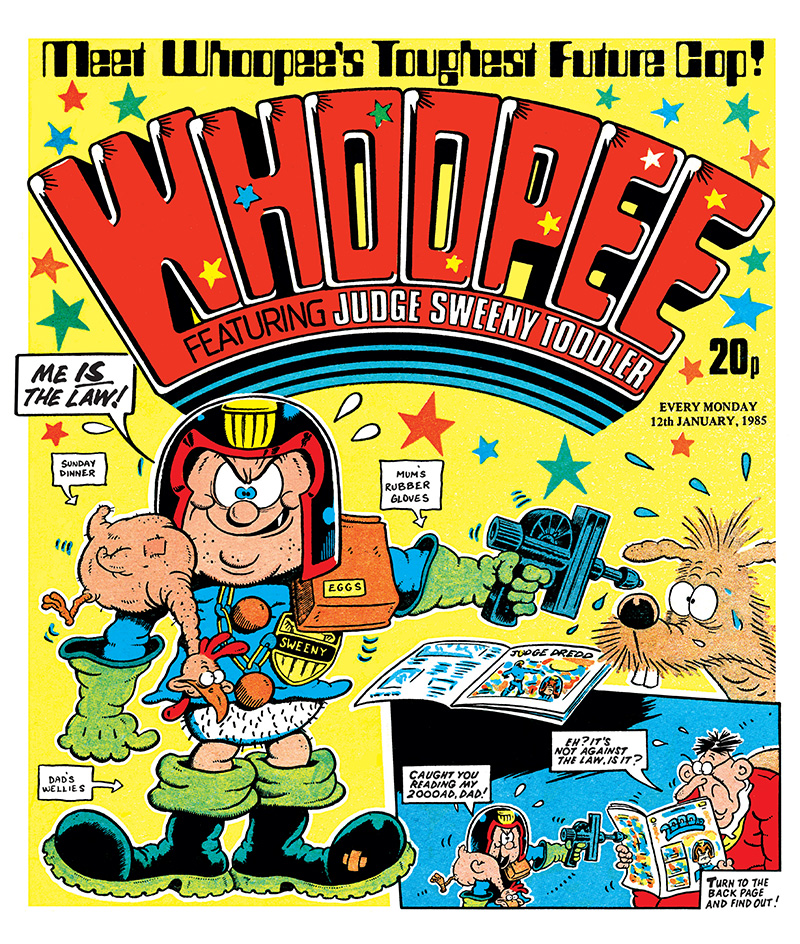

The mid-eighties saw the decline of the Annual’s popularity. Fleetway Annuals dated 1985 could be seen as the last hurrah for a lot of titles as the following year output nearly halved.

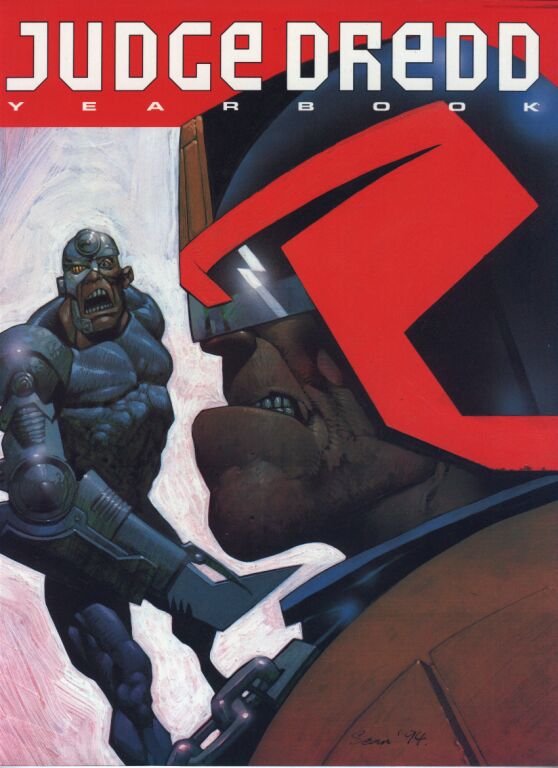

Like the weeklies, they were in less demand, and competition from television and computer games for kids’ attention and pocket money saw the comic market dwindle. By the early nineties Fleetway published only a handful of Annuals, with 2000 AD and Judge Dredd published as softback ‘yearbooks’. The classic ‘A Fleetway Annual’ logo was revamped in 1992, dropped in 1993, and in 1994, the World Distributors logo appeared on the Annuals, a sign of various mergers and acquisitions within comic publishing at the time in the UK.

1994 was the last year of classic hardback Annuals from the Fleetway stable, only Whizzer and Chips, Buster, Roy of the Rovers and Big Comic Book were published. 1994 was also the last of the 2000 AD and Dredd ‘yearbooks’.

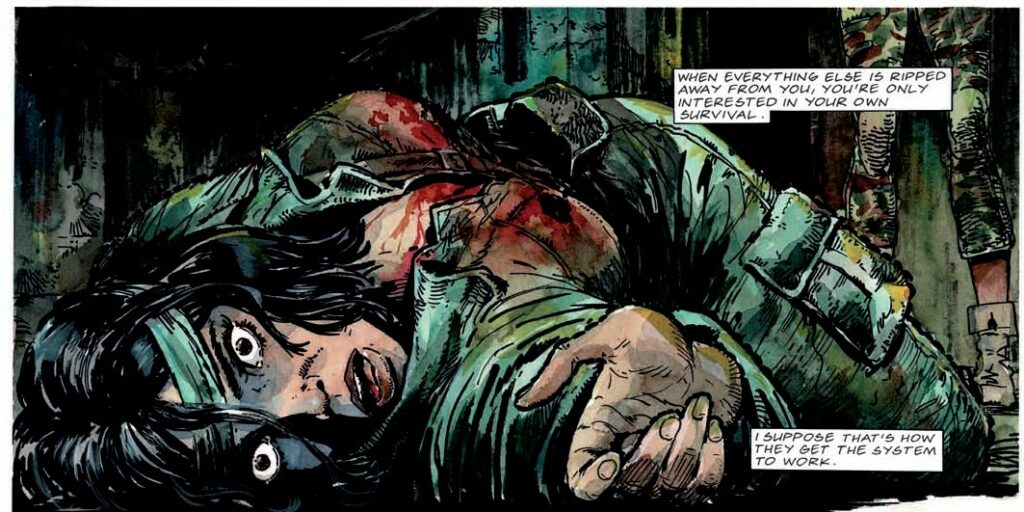

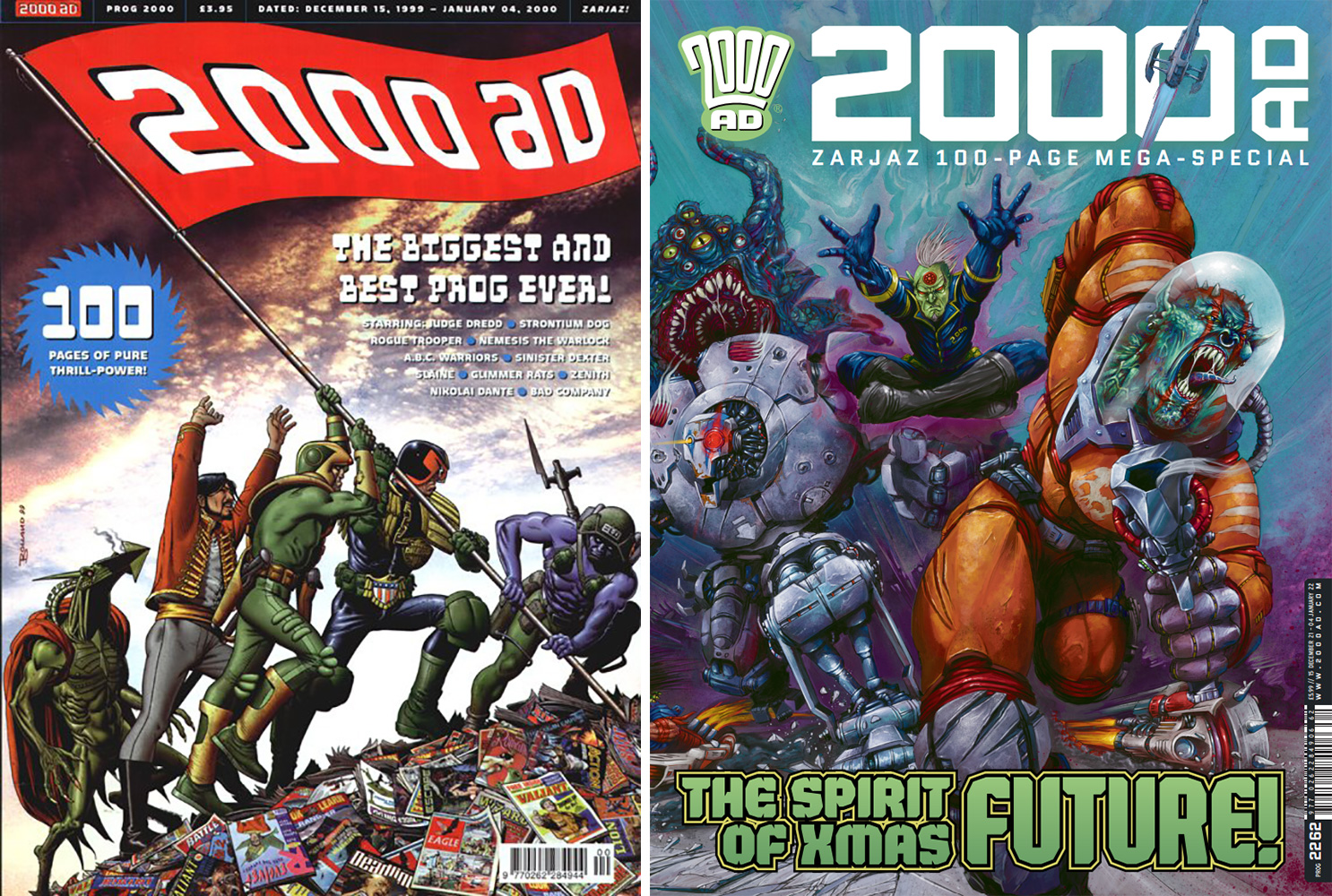

2000 AD did return to the tradition with its ‘Prog 2000’, published in the year 2000. It was a perfect bound softback year end issue of 2000 AD and along with the Judge Dredd Megazine it continues these end of year special issues to this day. This year’s is available now in all good newsagents!

While the golden age of Annuals is long past, they still are a Christmas institution in many homes, with the indomitable Beano Annual still leading the charge as the bestselling title each year.

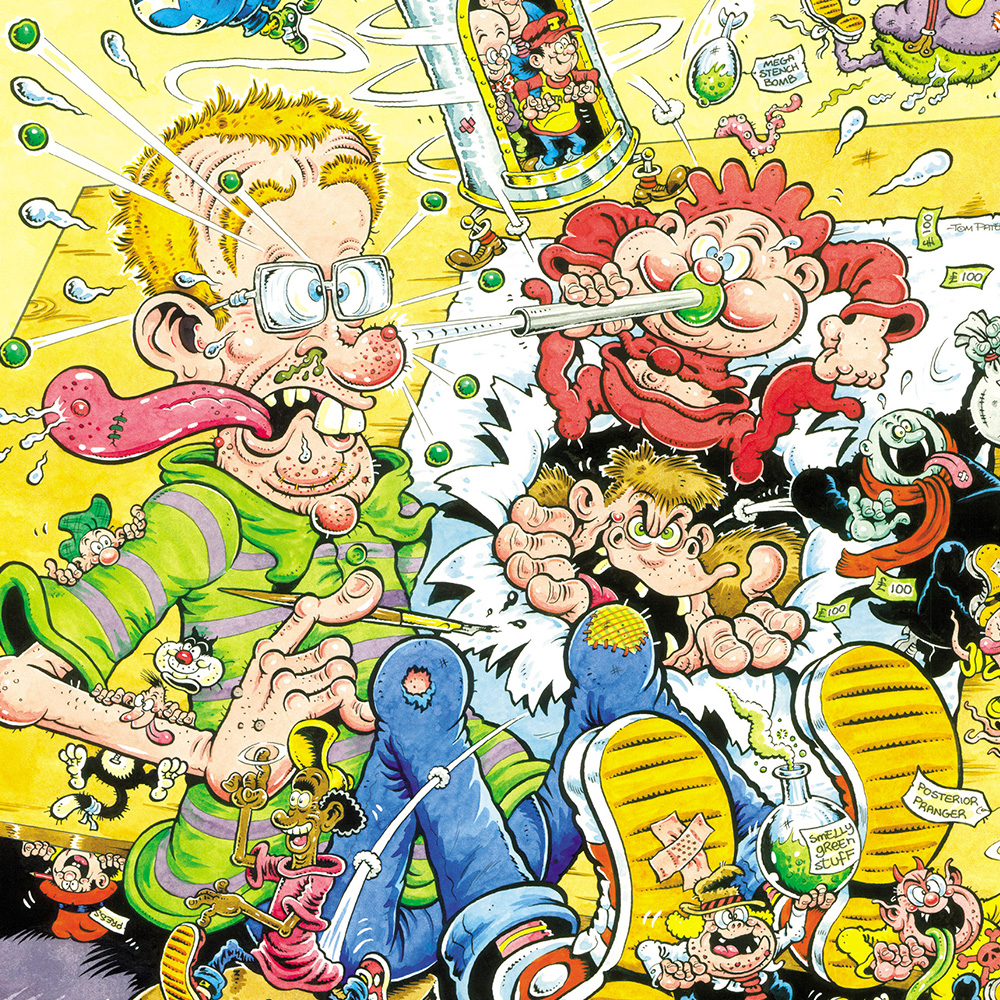

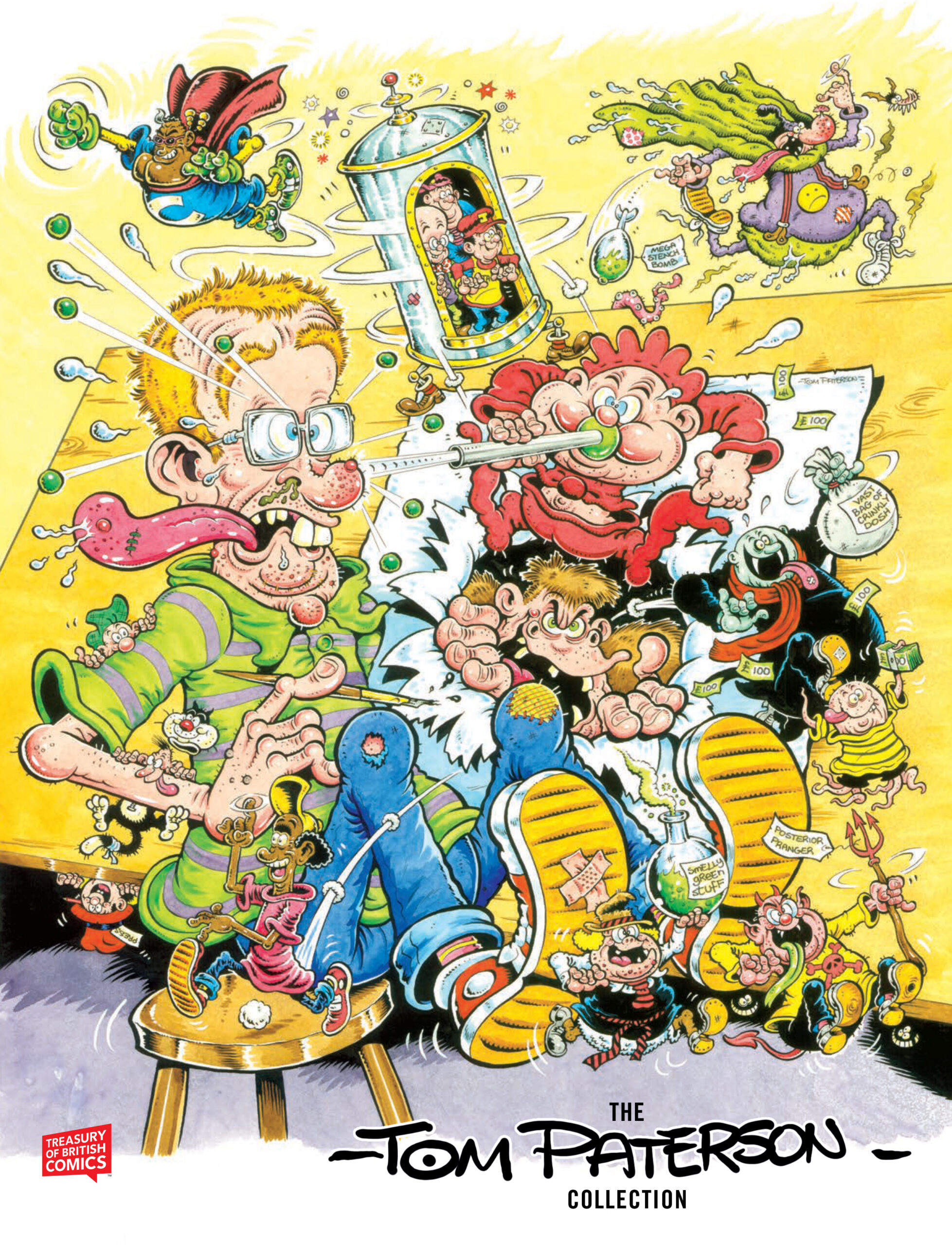

What are my favourite Fleetway Annuals? I hear no-one asking but to round up, here they are anyway!

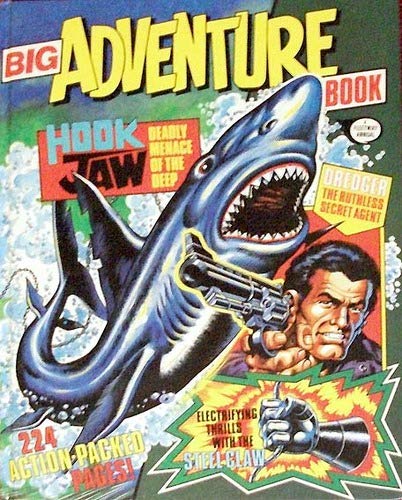

Big Adventure Book 1988

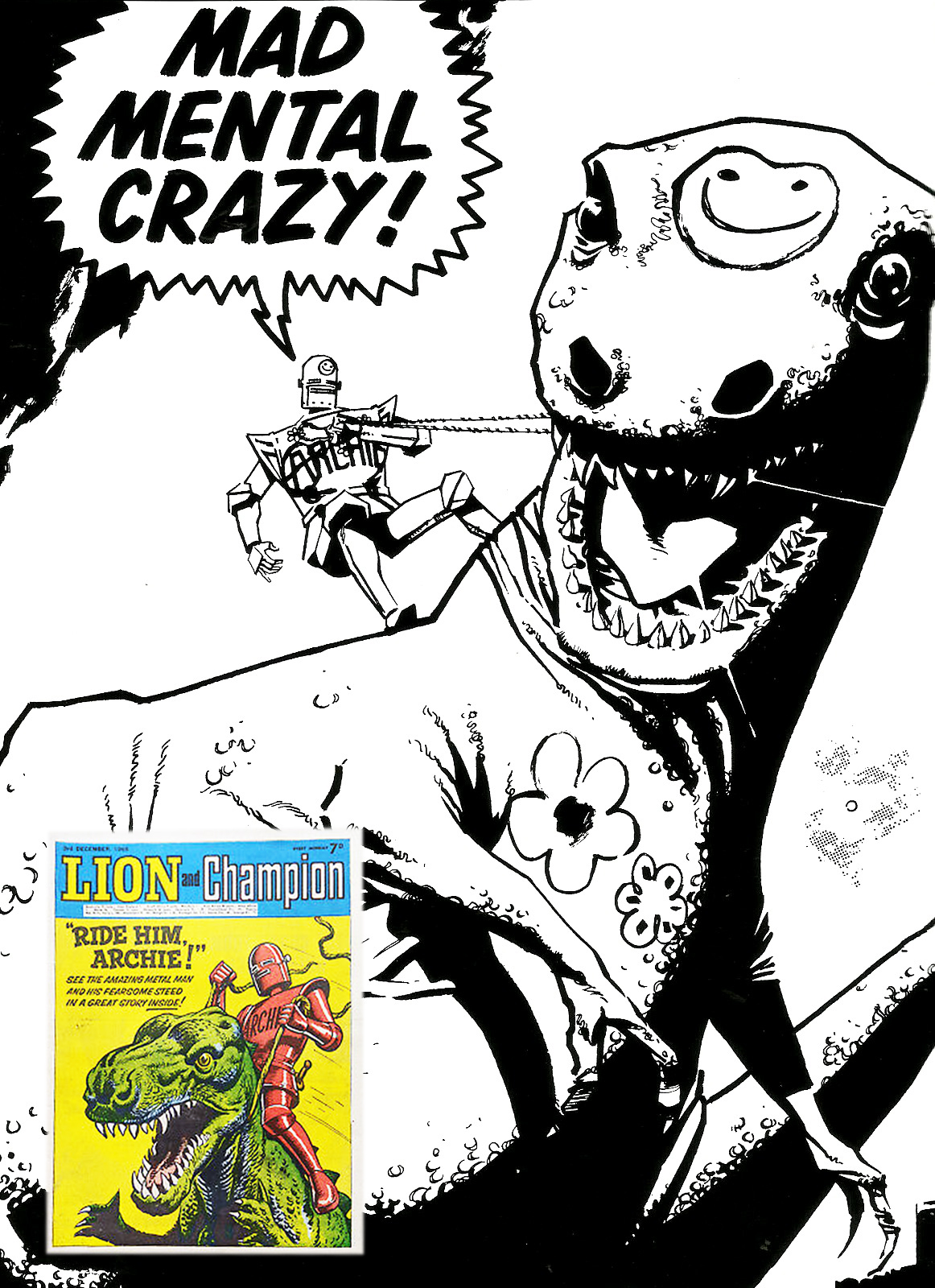

Cover by Sandy James, its 244 pages has a great eclectic range of reprints – The Steel Claw, Hook Jaw, Dredger, The Black Crow and One-Eyed Jack.

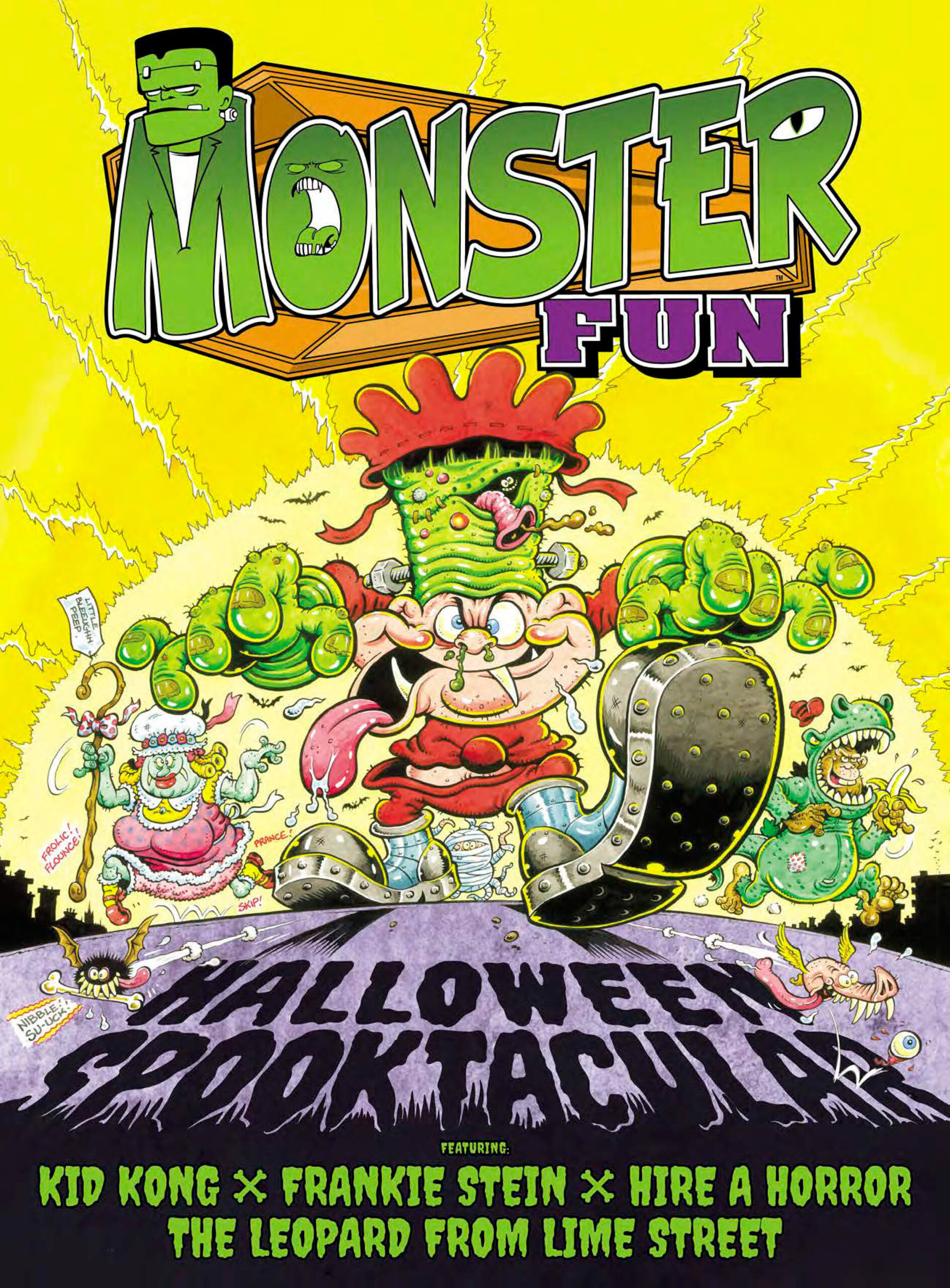

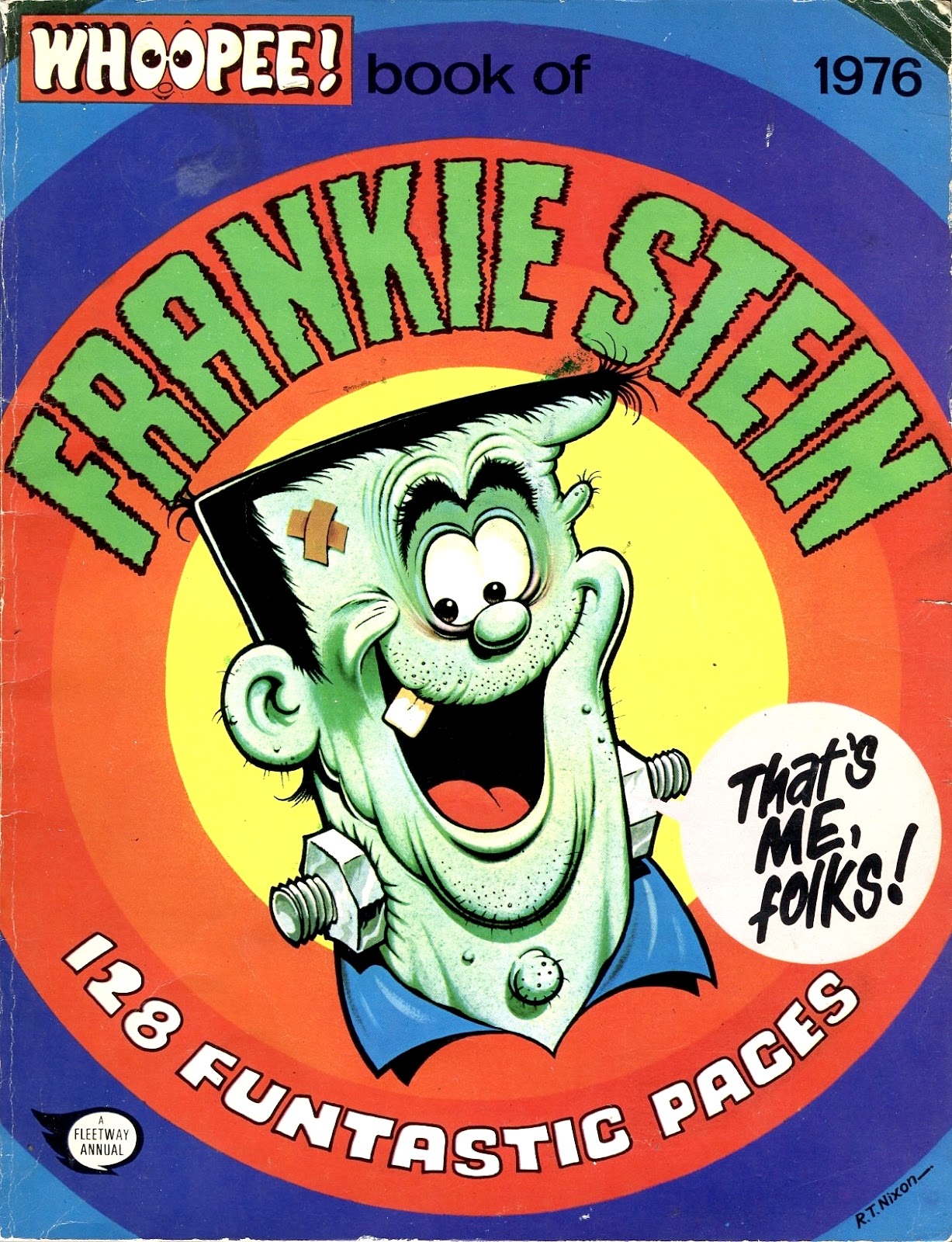

Frankie Stein Annual 1976

With some prime Robert Nixon art, (worth being on this list for the cover alone), mix in some Frank McDiarmuid art with Ken Reid reprints and you have a great book.

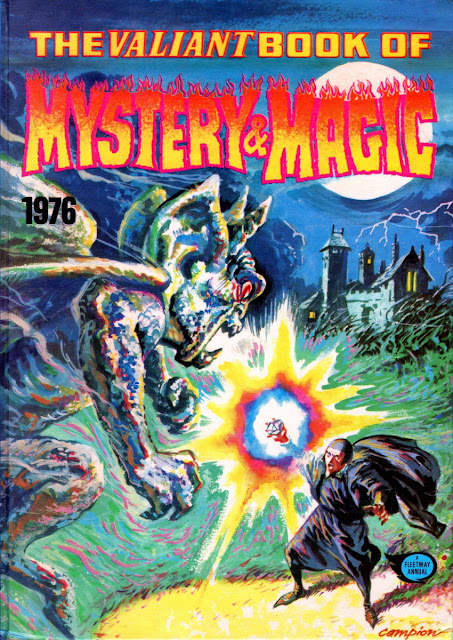

Valiant Book of Mystery and Magic 1976

Edited by Chris Lowder, cover by Geoff Campion. It reprints The Spellbinder from Lion as well as new material by Pat Mills, Eric Bradbury, Angus Allen and Joe Colquhoun (who draws himself in his story). It has the distinction of being the first IPC published title to include creator credits.

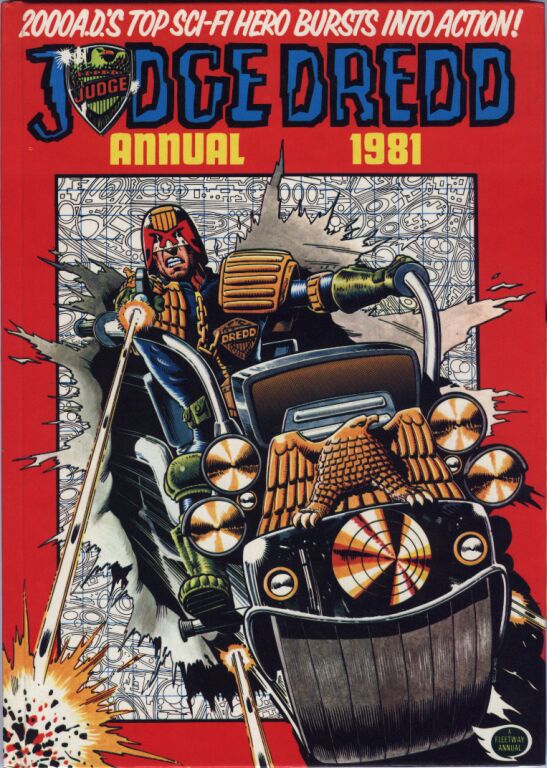

Judge Dredd 1981

Probably the first Fleetway Annual to contain nearly all new material, prime Mick McMahon art mixed with John Wagner scripts, wrapped neatly in a Brian Bolland cover, hard to top!

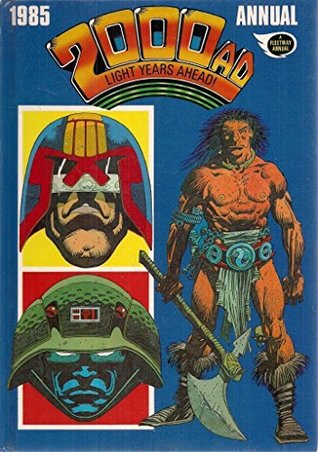

2000 AD Annual 1985

My favourite. Behind an amazing McMahon cover, the art by Belardinelli, Dillon and Higgins, Gibson and Smith make this the best looking Annual ever published. The scripts by Mills, Moore, Wagner and MacManus are not too shabby either!

With thanks to David Hunt, Kevin O’Neill and Mary McDonald.

David McDonald is the publisher of Hibernia Comics and editor of Hibernia’s collections of classic British comics, titles include The Tower King, Doomlord, The Angry Planet and The Indestructible Man. He is also the author of the Comic Archive series exploring British comics through interviews and articles. Hibernia’s titles can be bought here www.comicsy.co.uk/hibernia. Follow him on Twitter @hiberniabooks and Facebook @HiberniaComics

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.