Welcome back to the Brink – to mark the new collection from Dan Abnett and INJ Culbard’s claustrophobic sci-fi procedural Brink, comics critic Tom Shapira examines how the series reflects a horror that is both profound and, for our world, all too prescient…

As I am writing this article the media is still talking about Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos making their way to space. Granted, they’ve just barely made it, to the lowest rung of what we call space, but they are already talking big game about colonizing the solar system. Musk stated that Earth is basically kaput, and that the only way for the species to survive is off planet: “History is going to bifurcate along two directions. One path is we stay on Earth forever, and then there will be some eventual extinction event, the alternative is to become a spacefaring civilization and a multi-planet species,” but here’s the thing about space – space doesn’t want to us. It’s cold and hard, and lacking of some basic necessities (like oxygen).

People sent to space for any length of time nowadays go through rigorous physical and psychological training to make sure they are well equipped to deal with various dangers of space living. What’s more, these people also have a dedicated ground crew keeping watch of their every move and advising them on how to proceed. Just putting on the right set of clothes to go out on the most basic of space-walks is a job in and of itself; And if anything goes wrong, the lightest thing, well… to quote a different 2000 AD serial – “You’re hit, you’re dead.”

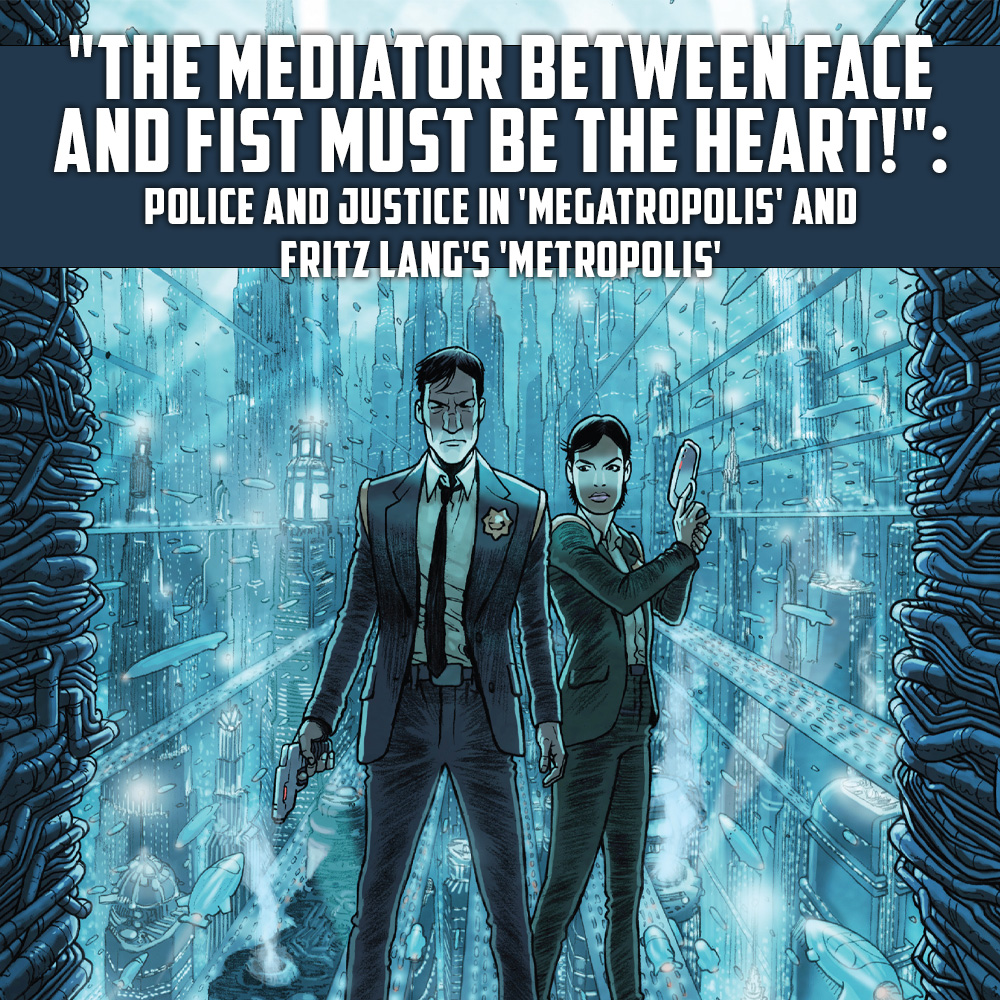

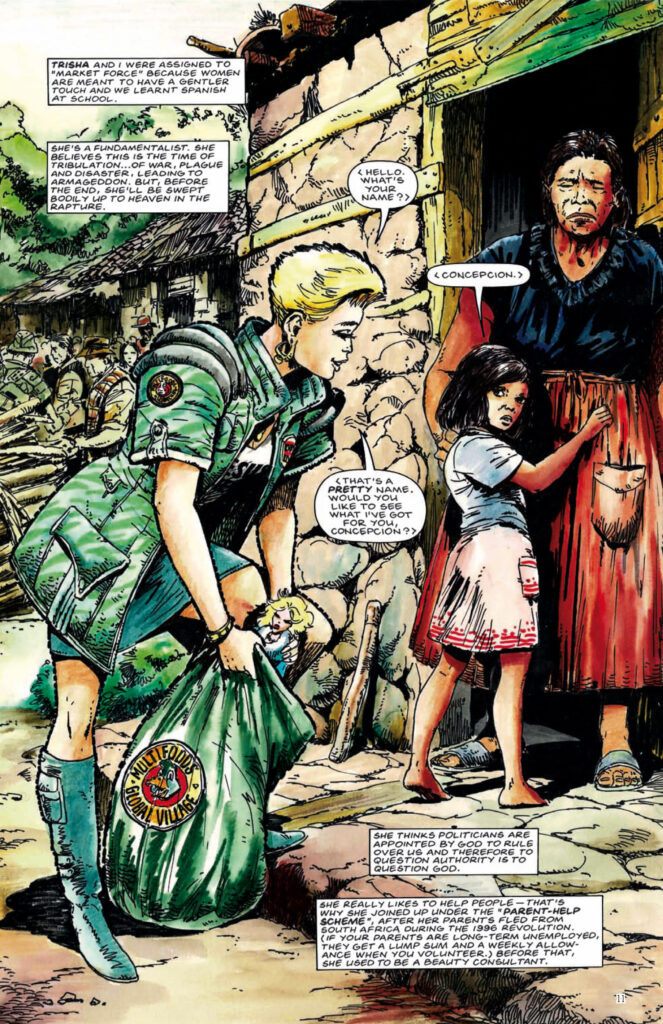

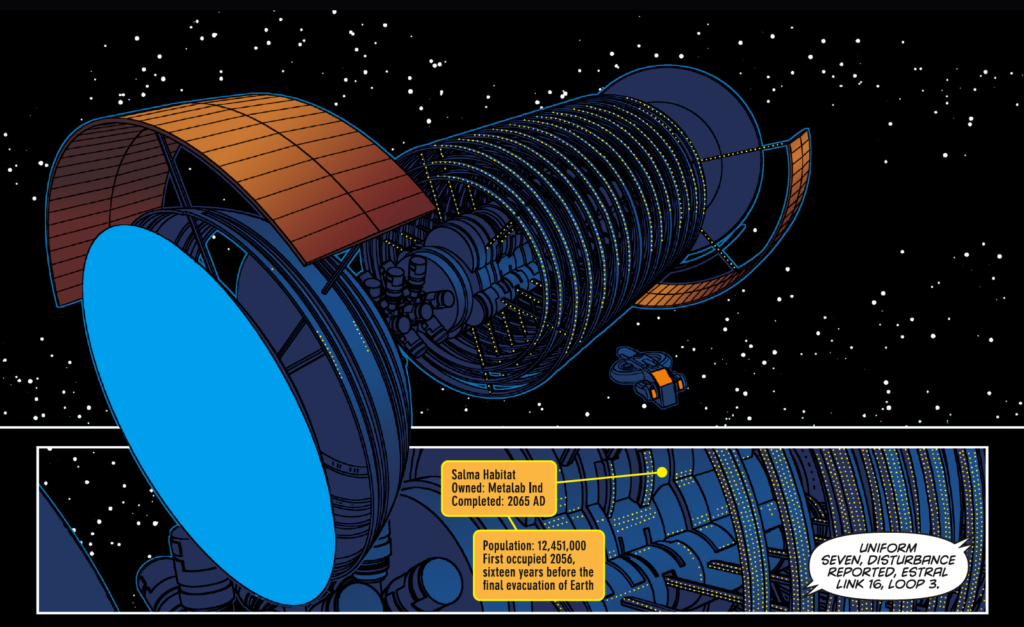

Which brings us to Dan Abnett and I.N.J Culbard’s ongoing series Brink. In this strip humanity has moved on to space and found out exactly how hard it is. Taking place several decades after the final evacuation of a now-unliveable Earth, what’s left of humanity is surviving in a series of artificial satellites, called “Habitats,” each holding hundreds of thousands to millions of people. Each habitat is a pressure cooker: space is at a premium and only the wealthy are able to afford more than few private feet to themselves, food options are limited and population just barley keeps by with a combination of prescription (and off-prescription) drugs.

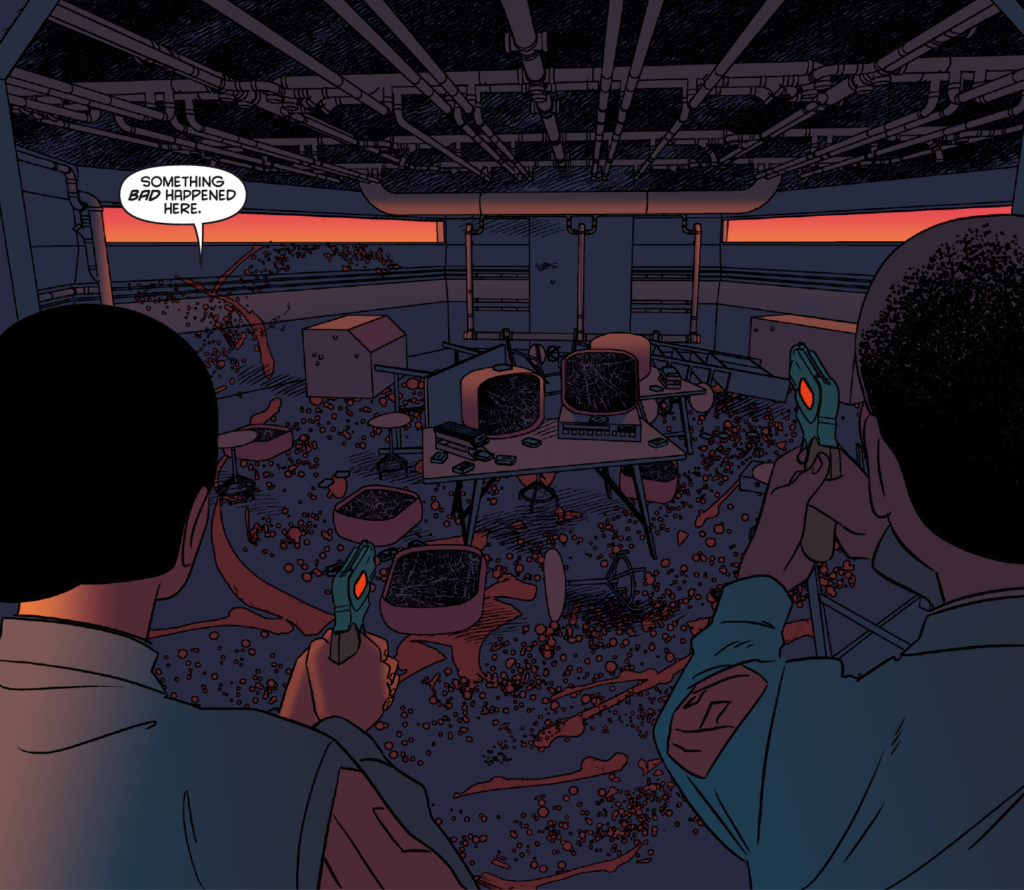

As opposed to many other 2000 AD strips, in which space travel is incidental and easy, Brink is dedicated to show you how gruelling this type of existence would be. Characters constantly appear (and act) haggard, art and text note the unhealthy skin tone of most people, reactions to public violence appear incidental – people have gotten used to it. Little surprise that space law enforcement, in the form of Habitat Security Division (HSD) have their hands full. Moving off planet didn’t solve any of the old issues, just imported them to a new environment, but it did create several new ones. Including a new series of dangerous cults that hold particular beliefs about the things that lurk in space, beliefs that appear at first to be unhinged… until they are not.

Book 4 of Brink is called “Hate Box,” that’s a good name. the titular box is the unofficial name of omnipresent device in Salma Habitat, the largest habitat we’ve seen so far, which gives $1 fines to anyone uttering a swear word. The inherent irony, that a mechanism meant to suppress the surface face of negativity becomes itself a target of constant seething rage, is obvious. More than that, however, the device is a constant reminder to ongoing state of humanity – for what are the habitats themselves if not tiny boxes filled with hate? Constantly reminding people where they are (while taking their money), does not alleviate stress. More than anything this reminds me of anti-homeless architecture – the problem isn’t taken care of, but is simply sent away so people can keep ignoring it.

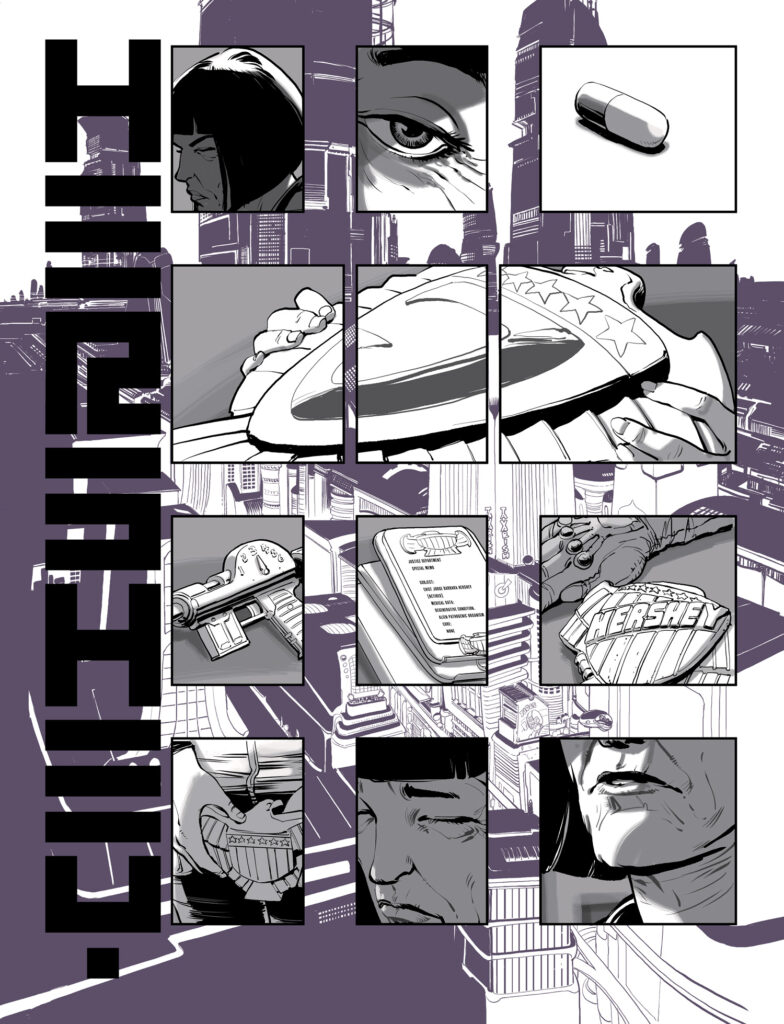

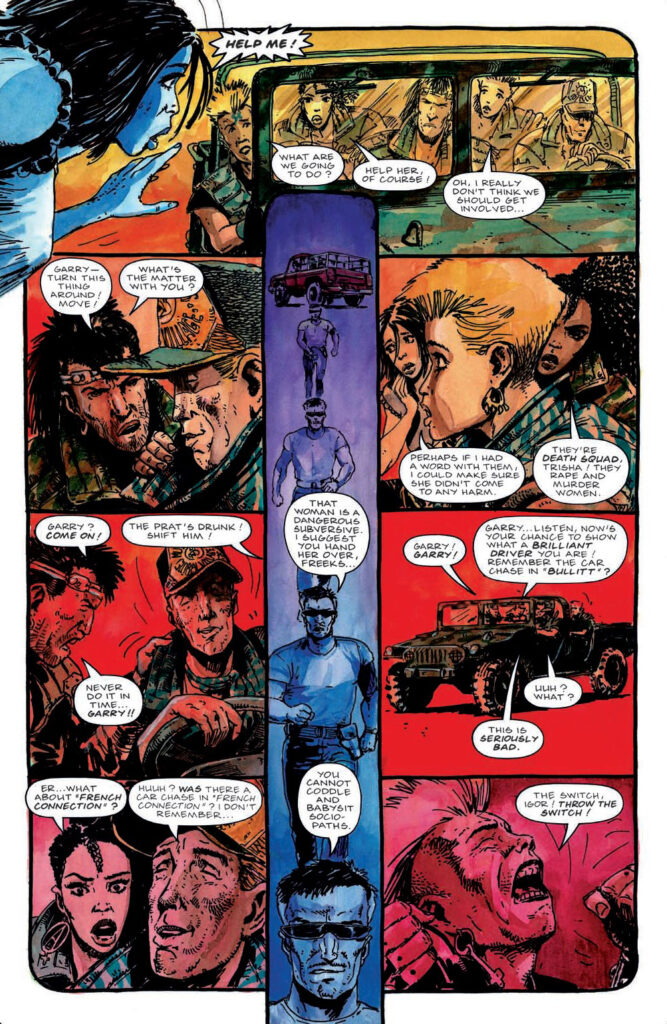

The key to Culbard’s art throughout is how cramped and tight it is – six to nine panel grids are the norm, and the layouts are often in the form of tight little squares. What appears, at first, to be simple conservative storytelling choice is revealed throughout to be rather brilliant mood piece. We experience the world as the characters do, as a series of cramped little boxes. Whenever the strip does allow itself to go big, a two panel page or even a full splash the results really are disorienting. Whenever someone of a lower status (most characters) finds themselves in an open space they kind-of freaked out, they can’t process all the extra room. Meanwhile, the rich (mostly seen in Book 2, “Skeleton Life”) have room to spare.

Culbard’s art style is also reflected in the scripts, particularly in the manner characters communicate – words are often precise and clipped. Partly this is the result of the story being a police drama of sorts, the characters often find themselves in high-tension situation and cannot afford any misunderstandings, but this is evident in civilians as well. Life is so dangerous, and room is at such a premium, that even conversations become cramped. When a miscommunication does happen you can see how frustrated people become about the waste of time. The constant I.D. tags, explaining various bits of technology, also work on the same wavelength – they give the whole proceeding a sense of professional report.

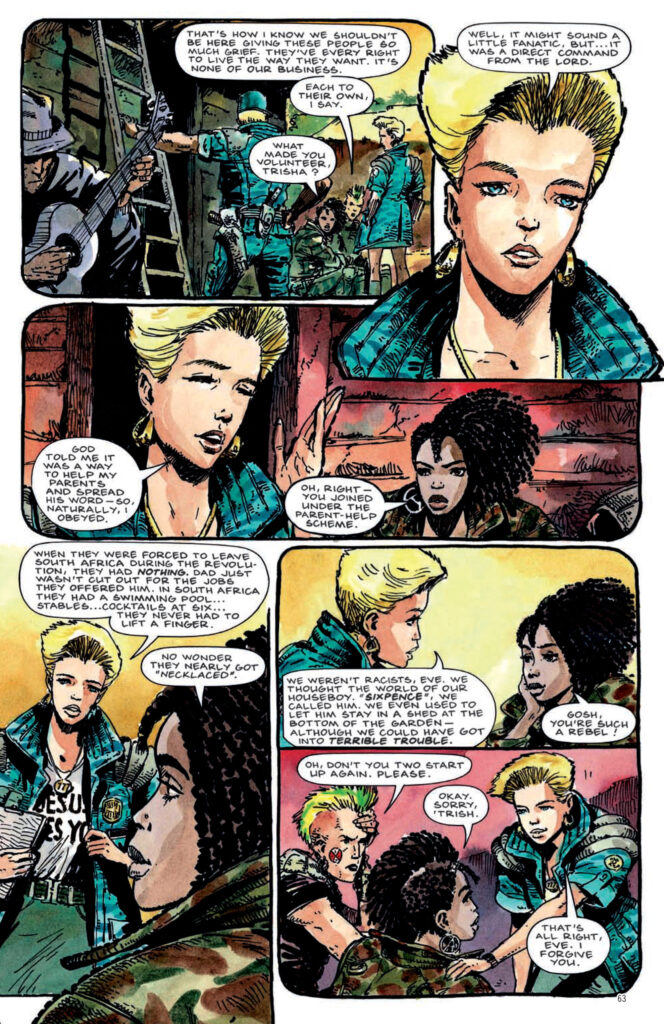

However, while everything is explained not everything is acknowledged. This is a main theme throughout Brink, and particularly in “Hate Box.” People ignore things because they are uncomfortable to talk about, people kicking the problem down the road hoping that someone else would take care of it. In “Hate Box” protagonist Bridget Kurtis is transferred to her old birth habitat, and discovers that the station is rife with crime and her precinct with corruption. Instead of doing something about it her new co-workers constantly tell her that that’s ‘how things are’ and that she should ‘learn to accept it.’ When Kurtis actually tries to take care of a major issue she’s called out for rocking the boat too much.

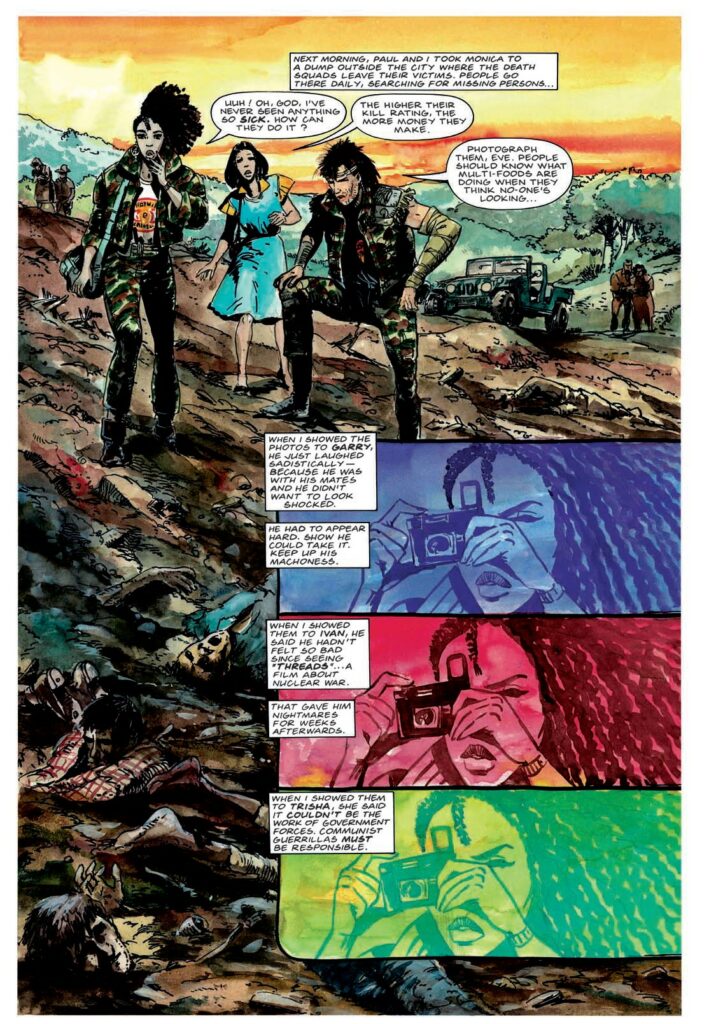

This, in itself, becomes symptomatic of the whole society. Living on the brink, seeing the inevitable fall, but being told to ignore it. The mysterious Mercury Event, which seemingly hunts the entire social infrastructure since the end of the Book 1, is constantly in the background. In his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed Jerad Diamond refers to this phenomenon as ‘creeping normalcy’: “When I asked my Montana resident friends about the change, they were less aware of it: they unconsciously compared each year’s band [of snow] (or lack thereof) with the previous few years. Creeping normalcy or landscape amnesia made it harder for them than for me to remember what conditions had been like in the 1950s. Such experiences are a major reason why people may fail to notice a developing problem, until it is too late.”

Kurtis notices that things are not as they were, but this takes a huge mental effort (and death of a partner that helped to anchor her in the ‘normal’ way of thinking). She still finds it hard, even impossible, to convince many others to see what she sees. Just like many people today refuse to see global warming for what it is – to acknowledge would disrupt the flow of their life too much, so they simple compartmentalise deadly heatwaves and mass fires as the ‘way things are.’

Brink is a horror story. I am not taking about the monsters that might exist in the depth of the sun, or the edge of the solar system. I am not even talking about the human monsters who would kill with abandon simply to keep the budget balanced (see Book 3). I am talking about the horror of the human condition, about seeing what’s coming and not being able to stop it. It is thus scarier than any story of a tentacled beast or a madman with a knife – they are just symptoms, this is the disease. Welcome to the Brink.

Tom Shapira is the author of Curing the Postmodern Blues (Sequart, 2013) and The Lawman (PanelxPanel, 2020). His articles about comics have appeared in The Comics Journal, Haaretz, Shelfdust, PanelXPanel and others.

Brink Books 1-3 are also available as an all-star audiobook adaptation. Listen now on Audible.

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.