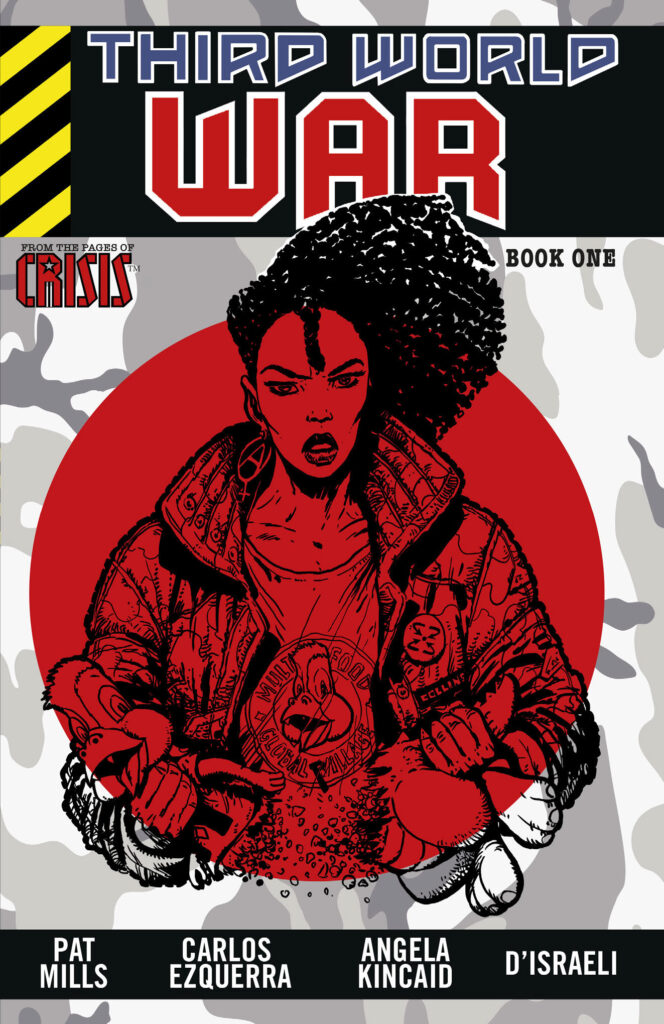

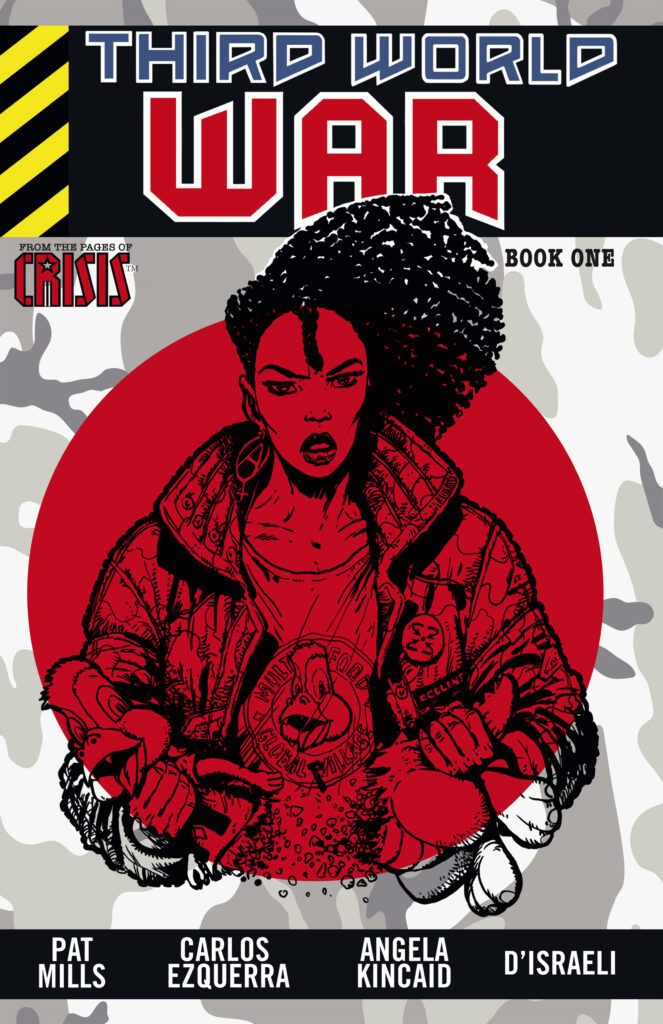

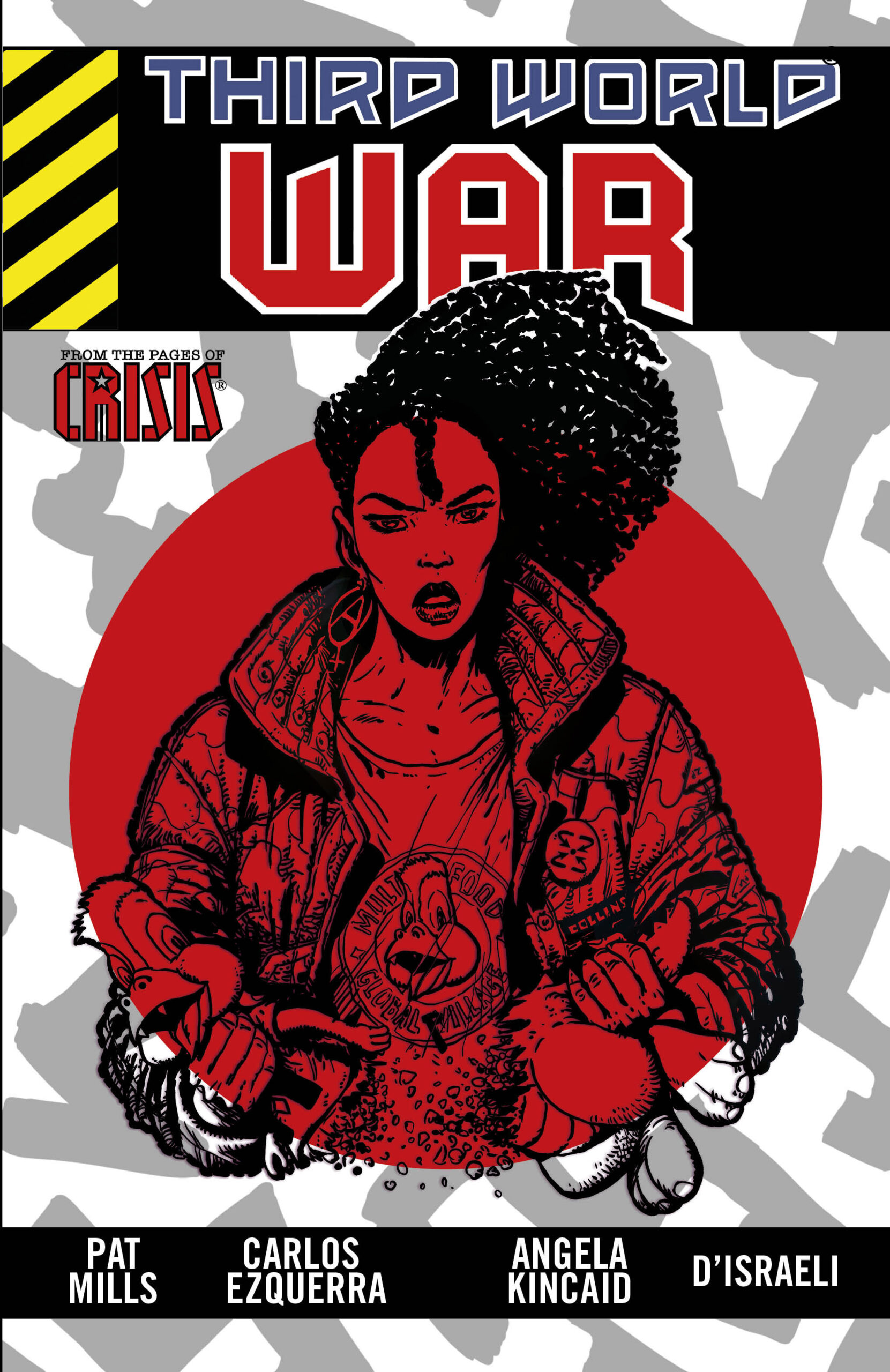

With Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra’s Third World War being reprinted in its entirety for the first time, the Treasury of British comics has commissioned short essays from selected comics critics that examine different aspects of this seminal political series from the pages of Crisis.

Tom Shapira’s essay on 3WW’s presiebce can be read here and in the second piece Kayleigh Hearn discusses the strip’s use of branding.

In the third and final piece, Kelly Kanayama, looks at the strip’s satire of American evangelical Christianity, embodied in the character of Trisha…

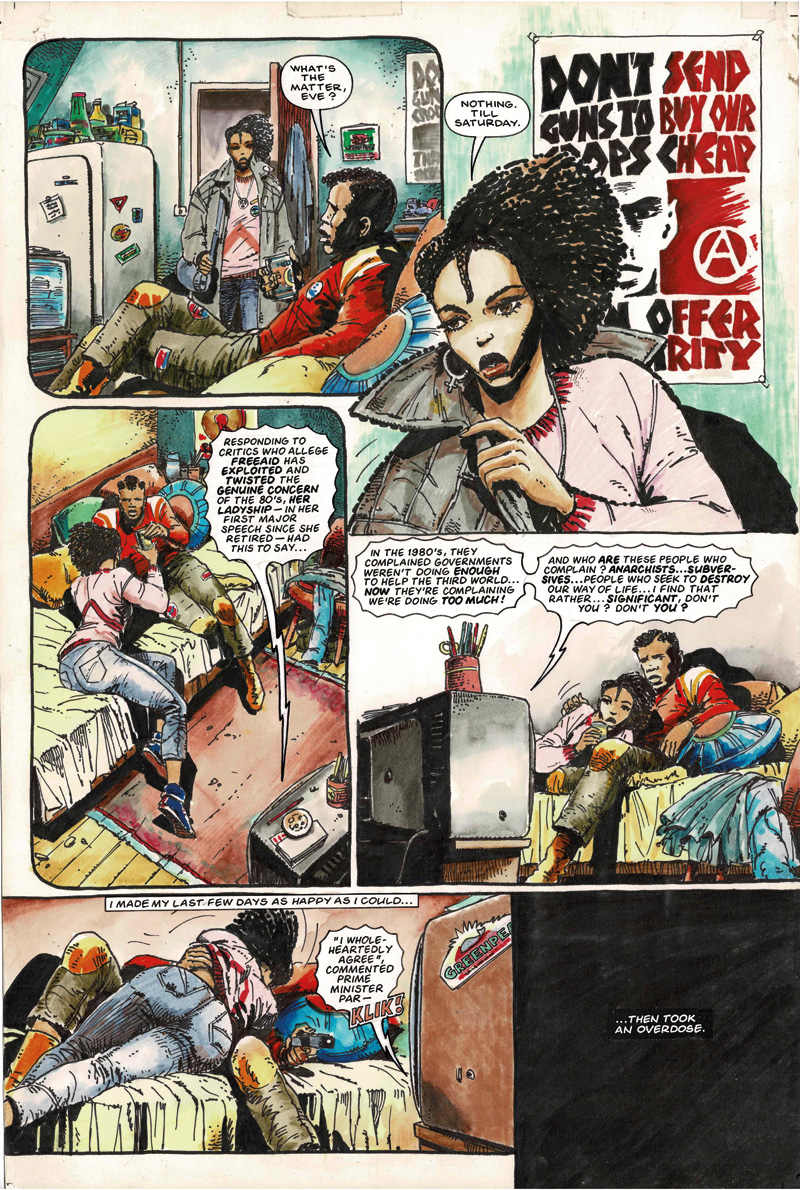

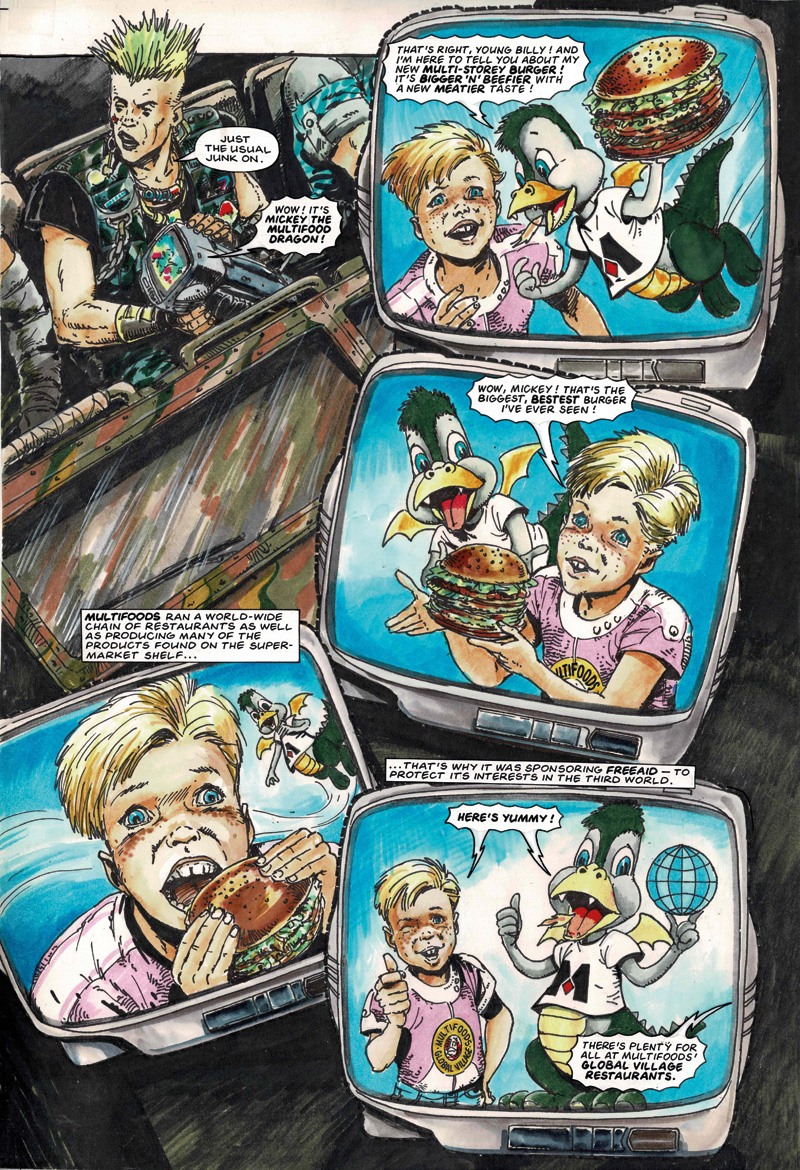

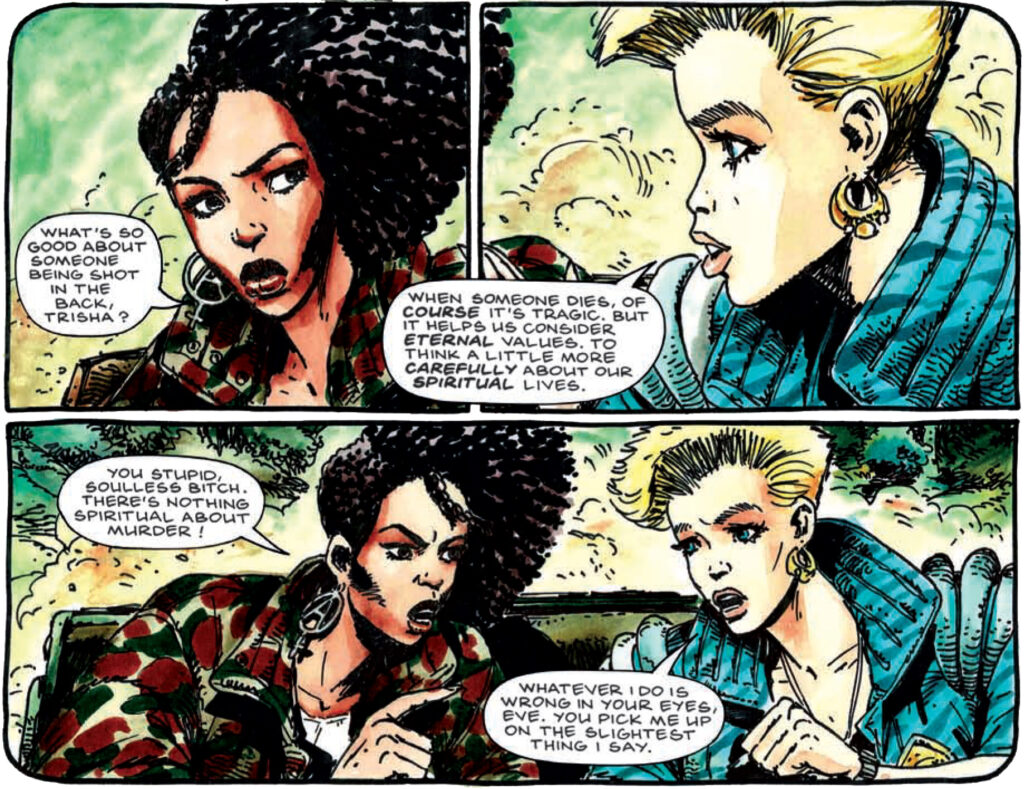

Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra’s Third World War is rightly hailed as a prescient satire of contemporary political and economic hegemonies, with its focus on the damage that globalised capitalism can inflict upon vulnerable populations. For me, though, what makes it really stand out is its recognition of the role that politicised evangelical Christianity would play in these dynamics, as embodied in the character of Trisha.

(I grew up evangelical, so am familiar with what that looks like. The comic that Trisha whips out to prove that roleplaying games are Satanic? I know that comic. I’ve been subjected to the messages of that comic. I’m wondering, right now, whether it’s worth it to buy my own d10s so my character in Scion can get a good roll for once.)

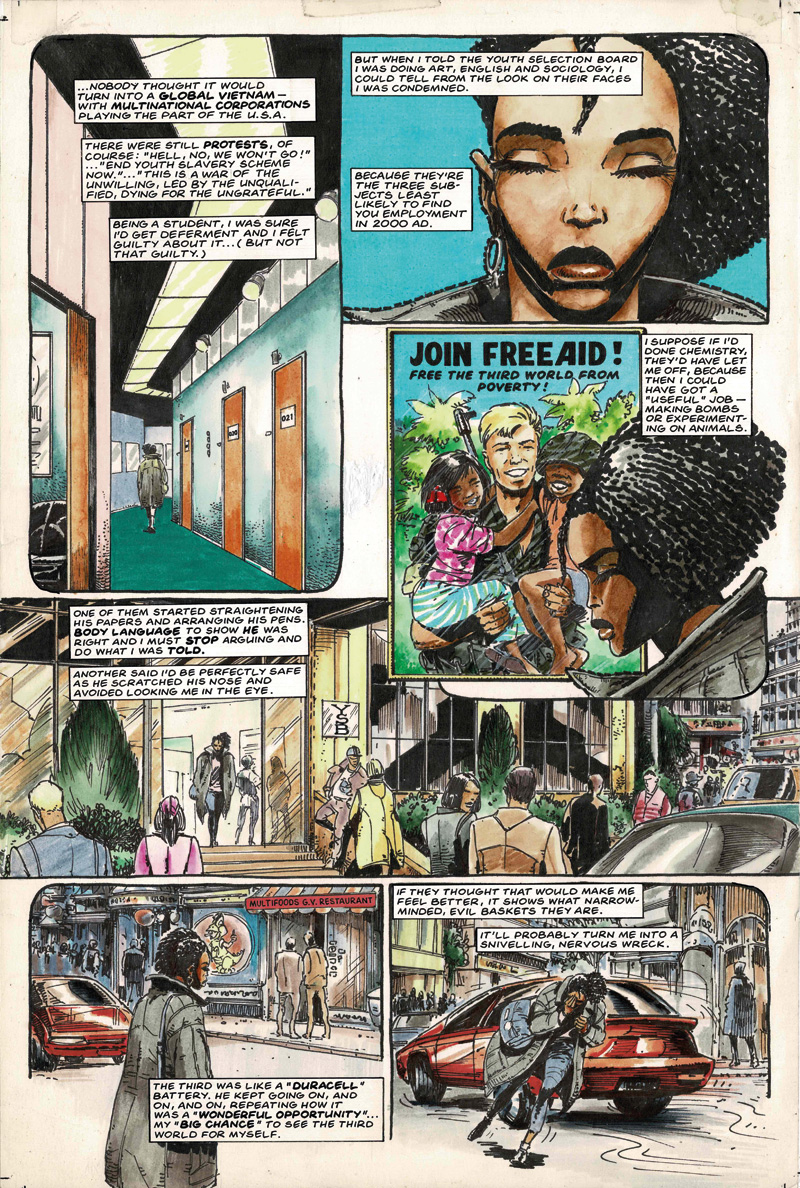

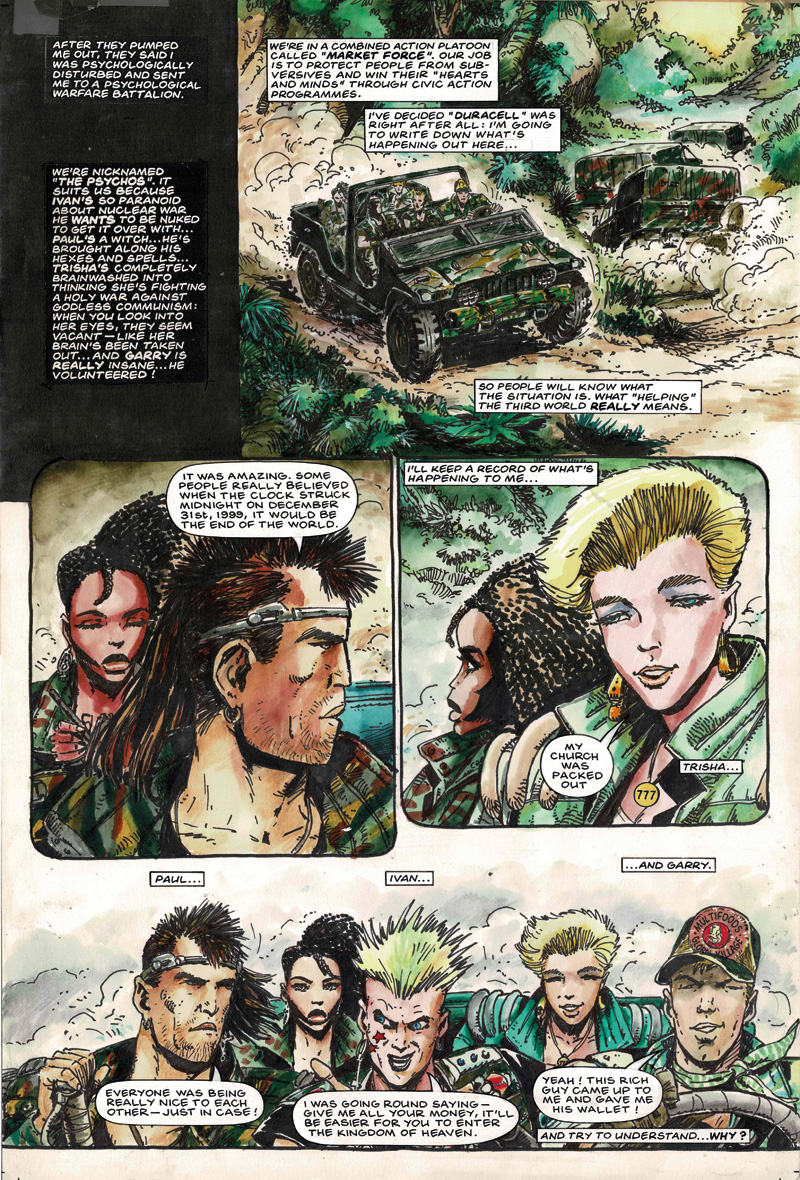

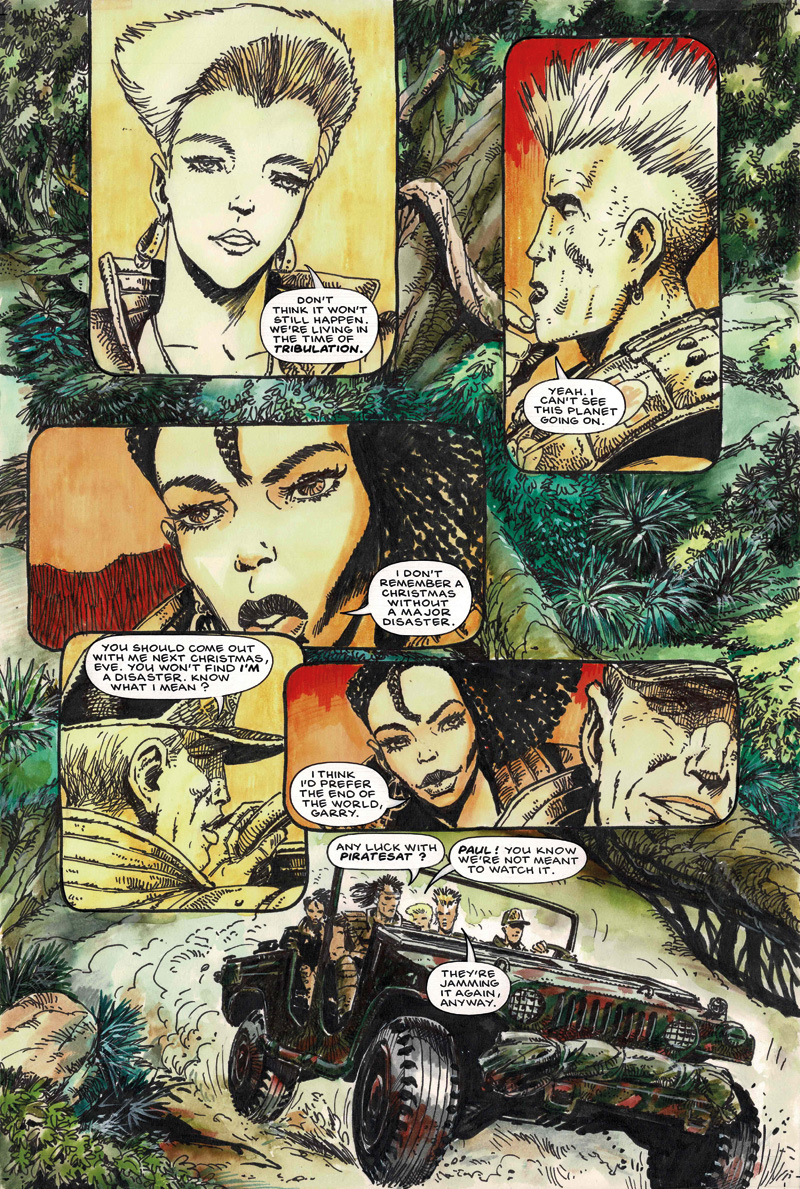

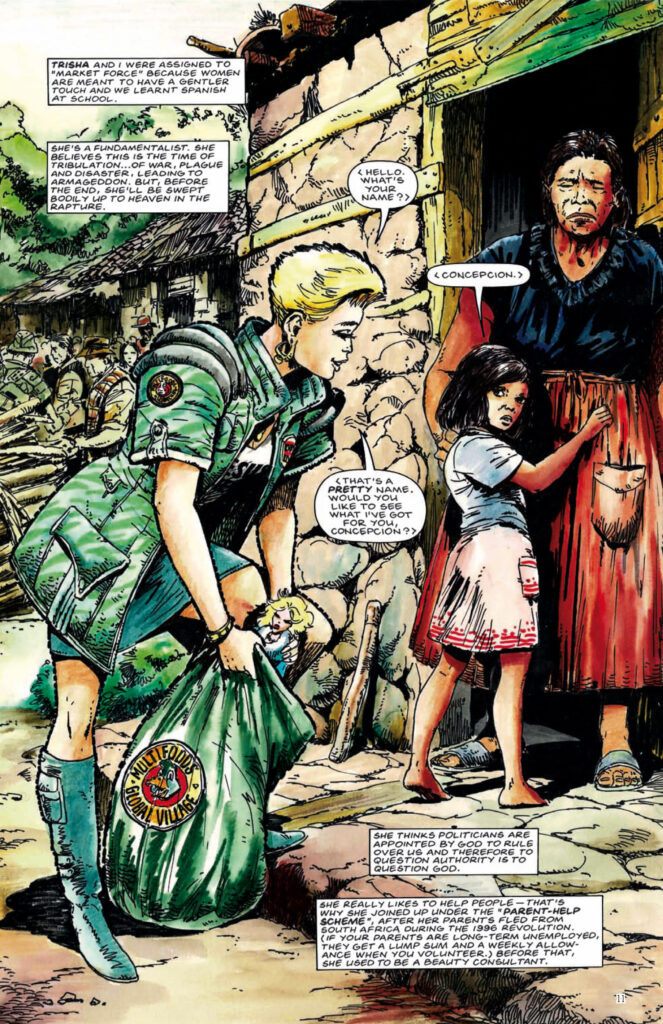

What makes Trisha so fascinating is her complete sincerity. As Eve notes, Trisha joins Market Force out of a genuine desire to help people – unlike, say, the swaggering, bellicose Garry, who mostly wants official dispensation to grind a boot into some foreign faces. Trisha signs up in order to provide for her ‘long-term unemployed’ parents under the Parent-Help Scheme, which provides a weekly stipend plus a single disbursement to people whose children volunteer.

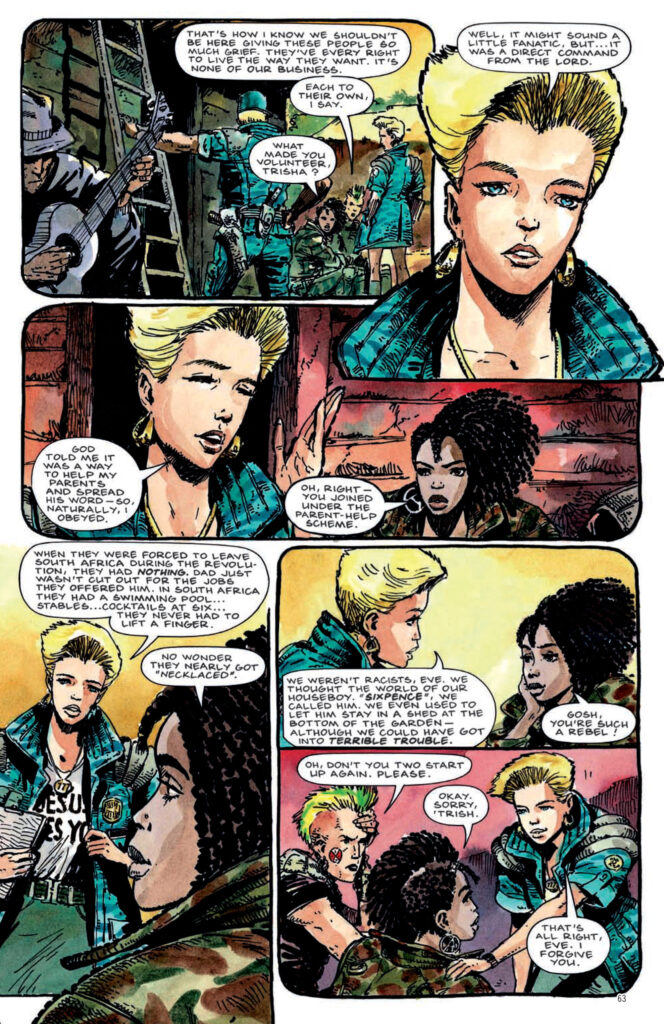

Of course, it turns out that her parents aren’t the most sympathetic characters. Trisha’s family fled South Africa after ‘the 1996 revolution’, which considering that she is white suggests that the revolution overturned apartheid; it’s worth remembering that Third World War debuted two years before apartheid was repealed in South Africa, and five years before the first South African general election where the country’s black citizens were granted full suffrage. When telling Eve about it, she says that her parents’ unemployment was due to their inability to break away from their former privileged lifestyles: ‘Dad just wasn’t cut out for the jobs they offered him. In South Africa they had a swimming pool…stables…cocktails at six…they never had to lift a finger’. They also had a black houseboy, whom they called ‘Sixpence’ – his real name is not mentioned, presumably because Trish and her family never bothered to learn it even though they ‘thought the world’ of him – and whom they allowed to ‘stay in a shed at the bottom of the garden’ out of the supposed goodness of their hearts.

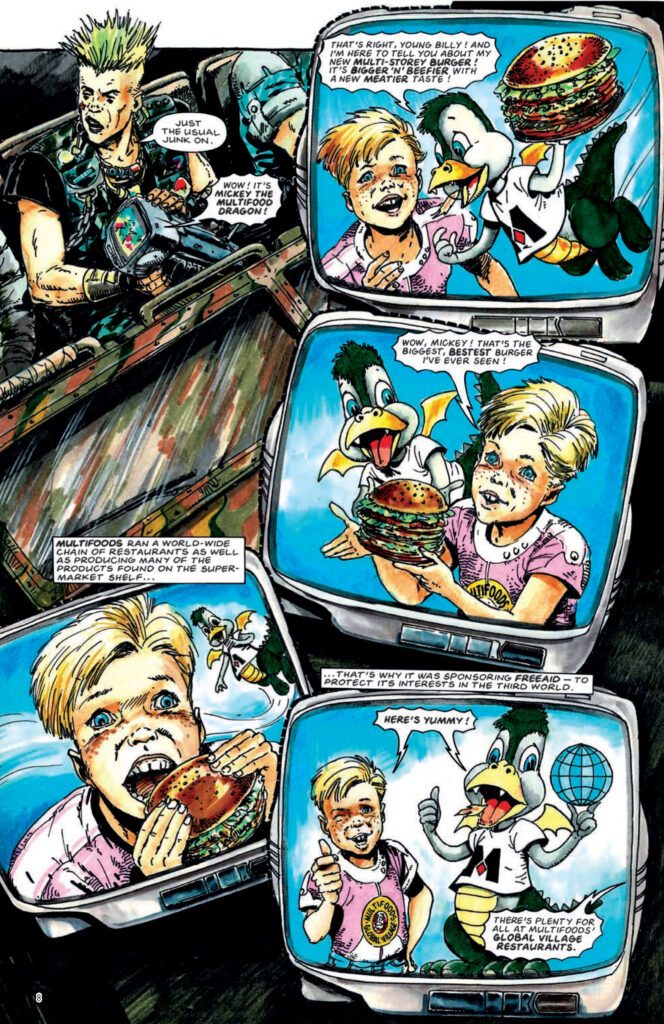

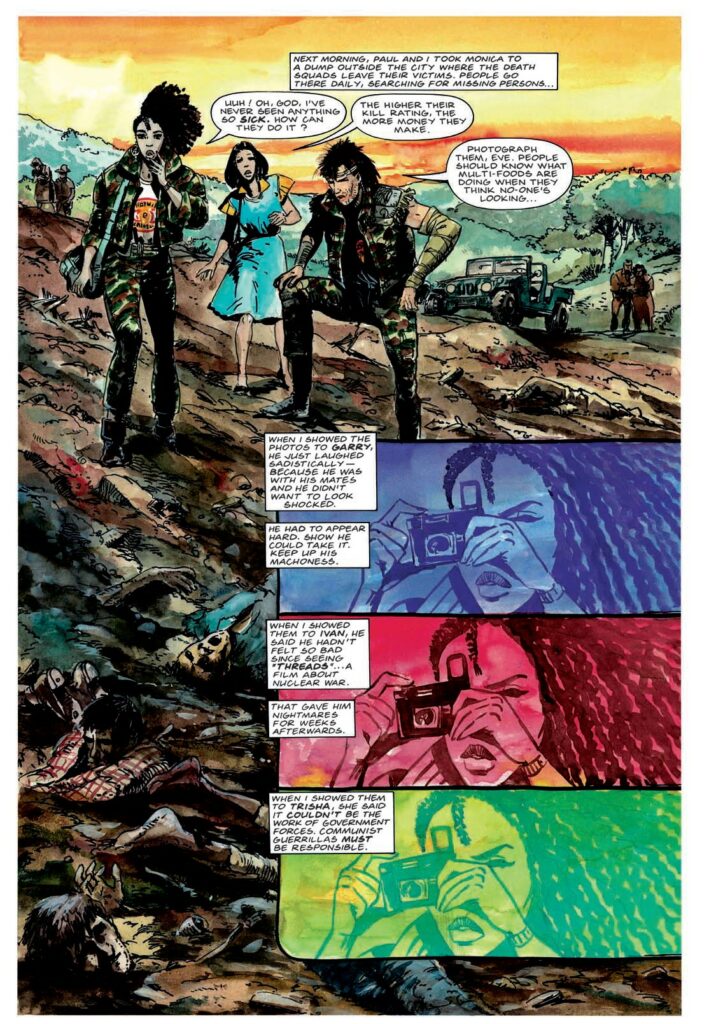

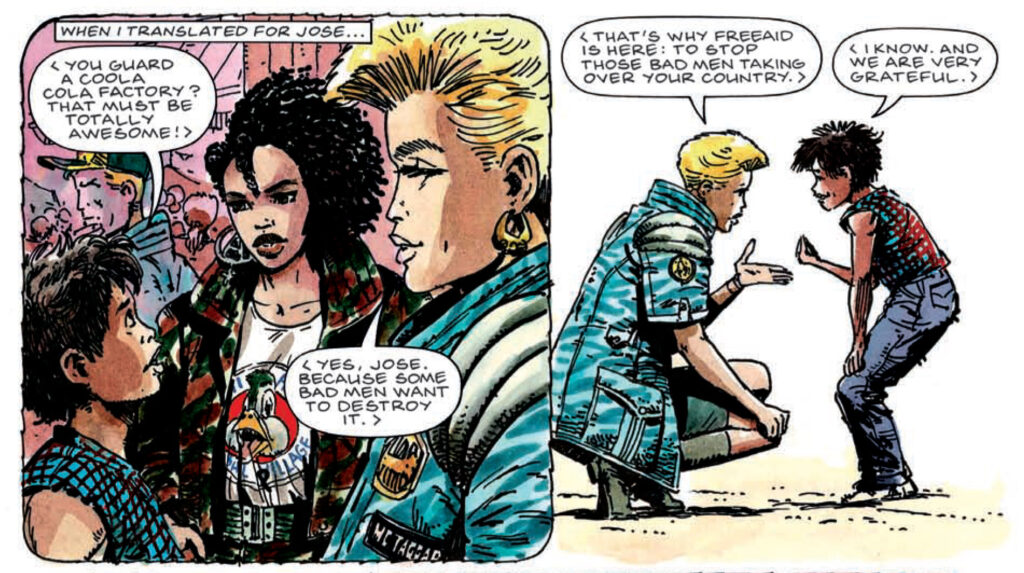

This short anecdote is highly illuminating in terms of how Trisha sees the world. While she may love marginalised people, it is a love that clings to authoritarian power structures: the same structures that marginalise said people in the first place. Thus it is virtuous that ‘Sixpence’ was given shelter, albeit in a form that excluded him from the very house he maintained. And thus it is similarly virtuous to spread the predatory corporate gospel of Multi-Foods, because they seek to promulgate a Western standard of living that falls in line with the greater power structure that has dictated Trisha’s life so far. As Eve puts it in her narration, ‘She thinks politicians are appointed by God to rule over us and therefore to question authority is to question God’ – a point emphasised by Trisha’s revelation that she initially joins Market Force because of a ‘direct command from the Lord’. Obedience is paramount: not just obedience to one’s chosen individual journey, but obedience to the institutions, voices and structures seeking to dictate that journey.

The point of delving into all this is to say that we are in Trisha’s world now. While there are of course numerous incredibly complex factors surrounding the rise of Trump in America and the snarled mess of whatever Brexit currently is in the UK, what underpins both these phenomena is a collective belief in the powers that seek to keep the marginalised that way. No matter how benevolent or generous the manifestation of such belief might be, the fact remains that a lot of people – people with more melanin than you, or with funny last names, or who eat foods you don’t – are going to bleed, and I wish that were only a metaphor.

Not that this is entirely new. From about 2001 onwards, especially after 9/11, global politics were dominated by such a mindset, in the sense that the George W Bush presidential administration leaned heavily on the worldview put forth by the same sort of neo-conservative evangelical Christianity espoused by Trisha and, due to America’s international hegemony, much of the world followed suit. However, given that America was and is a locus of global militarism and corporatism, the unquestioning trust in authority required by this brand of evangelicalism became inextricably entangled with initiatives in these arenas as well. Which is how you get to a point where authority, or authoritarianism, can act with impunity, because a power you can’t argue with wills it.

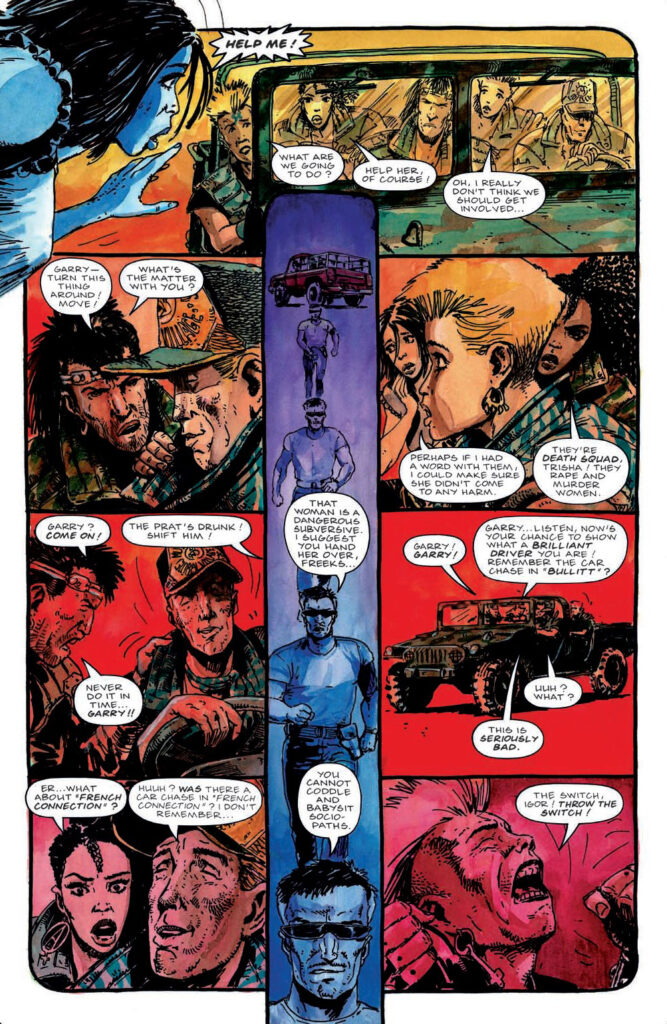

What gives me hope is Trisha’s turning point late in Book 1, where she faces a choice between knuckling under to the authority she has been taught all her life to obey and defying that authority – and thankfully she chooses the latter. The choice comes about when her unit is ordered to bring some orphaned children to their commanding officer, ostensibly so they can be rehoused, but actually so their bodies can be cannibalised for black market organs. When Trisha finds out what happens to the children they’re meant to retrieve, she lies to her commanding officer’s face, telling him that they didn’t find any children, even though she spoke directly to at least one child.

Such a lie might seem like a small step, but as someone who’s been bombarded with the messages of evangelicalism like Trisha has, I can tell you that it constitutes rebellion, which is a major sin. Rebelliousness was what got Adam and Eve kicked out of the Garden of Eden, and therefore is the reason we live in a world where bad things happen. To have a rebellious spirit is to reject God. And to reject God is to question the highest authority, or perhaps vice versa.

Trisha’s decision, therefore, signifies the possibility that the people who uphold the power structures that keep her going could expand their worldviews to fully acknowledge the flaws in said structures, even if it goes against everything they know. Let us believe that her real-life analogues are capable of following suit, and of opening the door to a less oppressive world.

Kelly Kanayama is a comics critic and scholar who was born and raised in Hawaii but now lives in Scotland. Her work has been published in the critical anthologies Working-Class Comic Book Heroes and Critical Chips Vol. 1 and 2, among others. Currently she is writing a book on the comics of Garth Ennis, to be published by Sequart.

Third World War is available now in paperback from all good book and comic book stores, online retailers, and the Treasury of British Comics webshop in paperback and limited hardcover editions.

All opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Rebellion, its owners, or its employees.